In a dark corner of the library in my Jesuit school in Ireland there was a large oil canvas. I could decipher a jungle of overripe fruit on tangled trees with monkeys and men leaping from branch to branch.

Hummingbirds flashed around. The picture had faded into sepia, but when it was painted in the sixteen century it must have been a festival of color. The title was Brazil.

The Jesuits in the 15th century sent missionaries to Brazil to colonize it for Christianity. They were in competition with the Portuguese who wanted to exploit the natives for gold and slavery.

The Soldiers of God’s approach was that of the Crusades. Force was used if necessary. While the Portuguese didn’t take prisoners to get what they wanted, the warriors of Christ did in order to make converts.

Their success led to banishment by the Portuguese in the 18th century, but Catholicism remains the dominant religion in Brazil. The painting was no doubt hidden, as the Jesuits methods were something of an embarrassment in the early 1960s, the time of the Second Vatican Council and good Pope John XXIII.

Brazil at the time was a military dictatorship mainly known for football and Rio Carnaval.

I felt there must be more to the fifth largest country in the world. Adventure stories by W.H. Hudson and Ian Fleming did not prepare me for Theodore Roosevelt’s Through the Brazilian Wilderness, a travel memoir that dug deep.

I discovered that in 1914 he wrote about the same tribe Claude Levi-Strauss studied in the 1930s. The anthropologist’s Tristes Tropiques (1955) thrilled my generation with its optimism for the New World, and Brazil’s Barravento beach became a destination for hippies and Pop singers.

But it was Euclides da Cunha’s masterpiece, Rebellion in the Backlands (1899) that drew me to the interior of the North East. It is a scientific work about survival in the semi-desert sertão that segues into the true story of when the local people took on the rest of Brazil in a fight to the death.

I met my future partner, Margaret, at a showing of Gláuber Rocha’s Antonio das Mortes (1969) in St Andrews film club. Her interest in the literature of the North East led me to João Ubaldo Ribeiro’s Sergeant Getúlio (1977), and the Brazilian concept of vara (‘If a problem does not have a solution, it is not a problem’).

This philosophy intrigued me. In the 1970s I was not unknown as a poet and playwright in Ireland. But realizing I needed to do something serious to support myself, I qualified as an epidemiologist.

While continuing writing, I worked free-lance engaging in research projects that essentially saw no problem without a potential solution. In the early 1980s this was rudely challenged by Aids, and I lost heart in my work for a time.

One afternoon in the mid-80s I offered advice to Oxfam on how to deal with the Indian communities’ move from a forest diet to a sugar-based one in their refugee settlements. Rotten black teeth were the norm for children. My recommendation was to put fluoride in their drinking water.

Fluoride is a waste product of the aluminum industry. Pedrinho, a Brazilian from the University of Salvador, whom I had helped with references for his doctoral thesis, identified the location of the factories and the bus network to transport the free industrial source to the Indian settlements. Pedrinho made sure the project got off the ground, and we became friends by letter.

On the back of that I decided to take my annual holidays in Brazil in the late 1980s and early 1990s. I had two pretexts: a reported outbreak on the São Francisco river of cancrum oris, a nutritional disease that had long disappeared in the West.

And secondly an interest in the Literature of the Cordel, street ballads by folk poets and musicians that served as newspapers for the illiterate. Their broad-sheets sold in thousands and they were often used as theme songs in Brazilian soap operas.

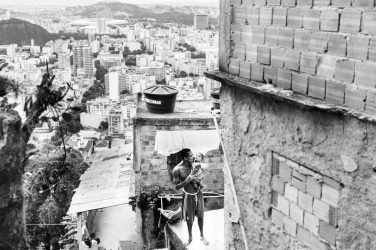

Travel is about bringing preconceptions down to earth. Rio despite its scenic marvels took me aback by its extremes of poverty and wealth, and latent violence. In order to fulfill my medical mission, Pedrinho arranged a military plane trip to the São Francisco river. The reports of cases of cancrum oris proved false.

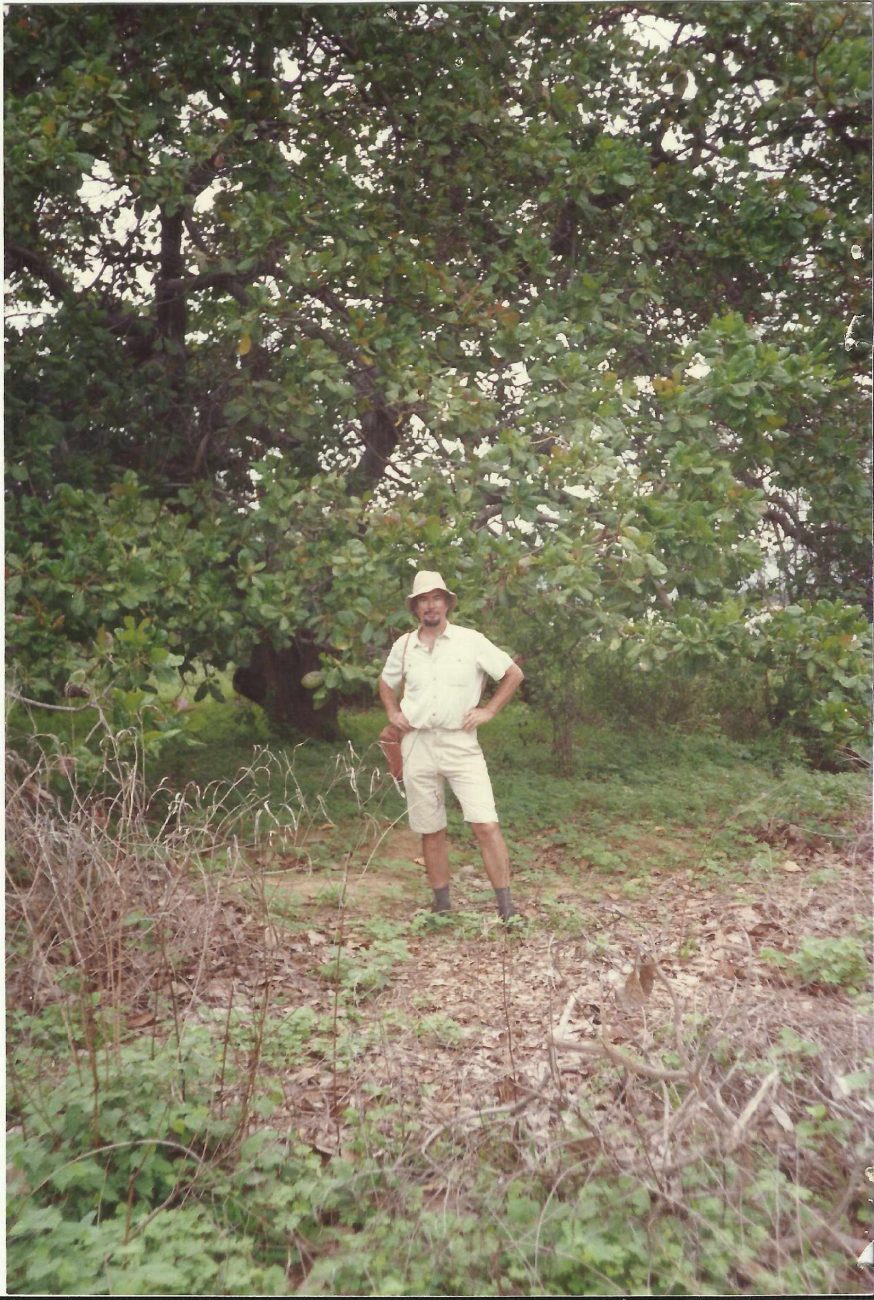

In order to get some measure of Brazil as a whole I flew to the Amazon, Rondônia, Brasília, Belo Horizonte, taking in the golden city of Ouro Preto. I wasn’t disappointed. But, sated by cultural tourism, I headed for the North East by bus, and immediately began to feel, if not at home, at ease with the people and myself.

I abandoned medical scouting, and concentrated on getting to know the culture of cordels. That did not prevent me from being drawn into a cholera campaign that went wildly amiss due to corruption.

I kept diaries of my experiences, and reported back to Pedrinho. My five Brazilian summers coincided with the country’s re-emergence into democracy, and it seemed on the part of the electorate that vara reigned supreme.

There was nothing to be done with the problems of poverty, shanty towns or political corruption. Lula, the workers candidate, thought otherwise. But he hadn’t a hope. I decided to talk to Ubaldo Ribeiro, whose novels exemplified vara, and yet he was an enlightened political journalist.

After spending a week with Pedrinho in his home town in the interior which hadn’t seen rain for ten years, my European moral doubts came to the boil.

Although I loved being in Brazil, particularly the back-lands, I became increasingly hot and bothered as I got to know close up the ‘compromises’ he had to make to keep his family in the middle class.

I argued with him like a Jesuit, forcibly trying to convert him to my values. He was merely perplexed. And I returned to London in confusion. It was to be my last visit.

To clear my mind I typed out my diary. And when Margaret read it, she laughed. ‘Is that what you were thinking while you were enjoying yourself? It isn’t what happened’. I published the sections about the Literature of the Cordel (Lampion and his Bandits, Menard Press, 1994, and my attempts to meet Ubaldo, Hopscotch, Duke University, 1995), and left it be. My friendship with Pedrinho was strained enough.

When Margaret died in 2012, I remember how happy she was in Brazil. The dry heat of the sertão suited her, and she learned to ride a motorbike in the jungle. I returned to my diaries and indeed what she loved was all there.

Only the latter chapters read like the diary of madman. I couldn’t help laughing at myself. And so in homage to her I rewrote it, trying to be as true as possible to my experience, worms, wonders and all.

As I could never write about her convincingly (we were too close, and that closeness came between Brazil and me), I replaced her in the narrative by the photographs she took with a box-camera. The auto-fiction Brazilian Tequila is the result.

Augustus Young was born in Cork, Ireland, in 1943. In his spare time, he enjoys traveling, particularly in Brazil. As an epidemiologist he has contributed to many medical journals, national newspapers and literary periodicals. His most recent publications include Memoire (Menard/ Duras Press, 2015), Diversifications: Poems and Translations (Shearsman, 2009), and The Nicotine Cat and Other People: Chronicles of the Self (New Island/Duras, 2009).