No wind can help those who don’t know where they are going. Though barely consolidated, the defeat of Donald Trump in the United States presents two apparently opposing views.

For some, like Brazilian journalist Ricardo Kotscho, the defeat drained the swamp that created the political miasmas that clouded the 21st century. There will certainly be a virtuous restoration of the recent past.

Others, like American lawyer and journalist Glenn Greenwald, on the other hand, believe that nothing will effectively change because the interests behind the Democratic Party and Joe Biden are, in essence, as oligarchic as those that kept Trump afloat.

These views fail to take into account the context from which the contemporary far-right arose – and how this scenario has transformed since the pandemic took hold.

For this reason, the opportunity missed by the left twelve years ago and the emergence of a new gap in the last few months eludes them – as does the effort required to take advantage of it.

This article supports four fundamental hypotheses:

a) Trump is not the cause, but the effect of a crisis of capitalism that started in 2008 and has not yet been resolved. However, the importance of the now-fallen president cannot be underestimated. He illustrated, even if symbolically, the pincer movement carried out by the financial oligarchy to escape the crisis. Such a move implied betting on two political blocs at the same time: classical neoliberalism and neo-fascism; and to build, through this combination, magical illusions that hid the ultra concentration of wealth and the dismantling of democracy;

b) This tactic could only be realized by taking advantage of an enormous political imagination deficit on the part of the left. In the face of the institutional crisis, the left failed to formulate a post-capitalist perspective. Astonished, it accepted the narrative that there was no other way but to save the banks and impose “austerity” and “fiscal adjustments” on the majority. In doing so, the left made the tragic mistake that has defined the last ten years as it paved the way for the far-right to put on an anti-establishment mask and gain a popular support that was previously unthinkable.

c) The COVID-19 pandemic is shuffling the cards again for two reasons. First, because it brings into focus the inability of the far-right to offer protection to the masses in the countries it governs. This failure, which can be deadly for a “populist” government, stems from the ties that Trump and Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro maintain with the financial oligarchy, which are increasingly more evident. Second, because the pandemic – which is now undergoing a “second wave” – exposes the fragility of the “solution” adopted in 2008 to face the financial crisis. In the coming months, there will be more economic and social devastation, which will open up room for discussion, once again, of the two opposite ways of facing the drama.

d) Similarly, in Brazil, the obscure atmosphere of the last two years may change. The lack of effective opposition has so far shielded Bolsonaro – unlike what happened, well before the US, in Argentina, Chile, Ecuador and Bolivia, for example. But the likely underperformance of the candidates he supports in the upcoming municipal elections shows that the climate of permanent confrontation he has created may have become ineffective. In addition, he will have to face, right after the election, a set of serious problems – unemployment, impoverishment, food inflation – to which his ultraliberal program has no answers. And, finally, it is very possible that the election will give rise to a renewed, plural left, less likely to accept the artificial polarization that the president uses as a political strategy.

It is worth examining each of these hypotheses in more detail.

Trump’s downfall could defeat the pincer movement of the financial oligarchy – at the very point at which the global crisis will again intensify and demand political definitions

I. The Pincer Movement of the Financial Oligarchy

Studied with enormous interest since Karl Marx, the crises of capitalism were seen as moments of revolutionary opportunity in the 19th and 20th centuries. In them, both the logic of accumulation and its ability to generate consensus are disrupted. The structures of bourgeois domination are shaken. There is a chance of profound transformations or even a breakdown of the old order.

Interestingly, only the least exciting part of these phenomena took place in the great financial crisis that began in 2008 and, in many ways, has not yet ended. In Western economies, wealth production and investment rates have recovered very slowly. In many cases, they are still below pre-crisis levels. Unemployment, insecurity and poverty increased.

Even in the United States, as the anthropologist Wade Davis reminds us, “a fifth of American households have zero or negative net worth… The vast majority of Americans – white, black, and brown – are two paychecks removed from bankruptcy”.

However, during this period, the class struggle – which Marx, Bakunin and Proudhon came to see as the “motor force of historical change” – developed in the opposite direction to what they had predicted. A tiny minority has taken over an even larger share of income and wealth.

But, instead of stirring up rebellion, this process produced the emergence of a far-right that celebrates and propagates the crudest values of capitalist domination. Individualism. All-against-all competition. Affirmation of brute force. Violence. Hatred of the different. Anti-communism, misogyny and racism. Contempt for solidarity structures.

The reasons that led to this emergency will be better addressed in the next topic, but it is important to note here that the financial oligarchy, the 0.1%, celebrated and supported the “novelty”. The soft fists of the great international bankers greeted the furious fists of white supremacists, or the armed fists of Brazilian militiamen.

It was functional for multiple reasons. Everywhere, the emergence of an artificial polarization (the establishment versus the right) attracted societies’ attention, avoiding those who debated the policies that produced inequality and impoverishment.

In some countries (such as Brazil), where traditional conservatism has proved to be worn out and unpopular, the billionaire class had no problem showing their outright support for proto-fascists. In others (such as France), the threat of the far-right (Marine Le Pen) was providential for the majority to opt for an openly neoliberal banker (Emmanuel Macron), seen as the “lesser evil”,

And this forceful movement goes far beyond elections: it contaminates the entire political debate. In Brazil, conservative media have actively contributed to Bolsonaro’s rise, either by “normalizing” his support of torture and his connection with militias, or by supporting him openly.

Depending on the circumstances, they may be on his side again, so it is important to never break with him. But now, when the media oppose some of his policies, they present, as an alternative, the supposed “wisdom” of Brazilian speaker of the House, Rodrigo Maia’s ultraliberal agenda, whose axis is to freeze social spending at any cost, even in the midst of a pandemic.

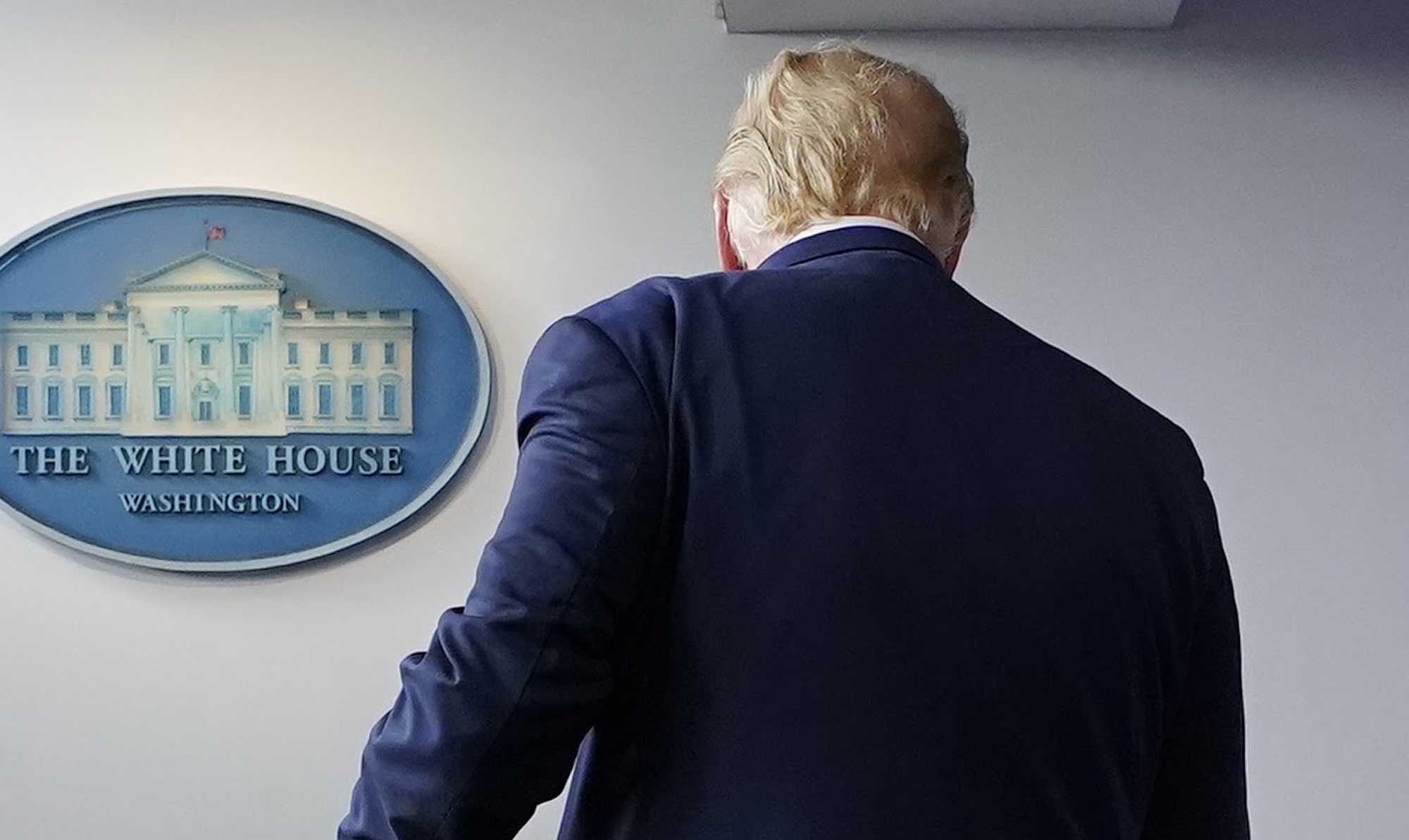

For this reason, and however big the limitations of Joe Biden may be, Trump’s failure is a fact of enormous relevance, with the potential to change the international political stage. It was the election campaign of the American president, starting in 2015, that took the far-right out of the corners, assigning to it the status of a valid political front to be taken into account.

It was his government that legitimized the resurgence of proto-fascism with real chances of power. It is his downfall, now, that could defeat the pincer movement of the financial oligarchy – at the very point at which the global crisis will again intensify and demand political definitions. And it takes place when the United States is immersed in social mobilizations with a clear character of acute criticism of capitalism, despite having no clear project yet.

II. The Great Political Imagination Deficit

Denouncing the pincer movement of the financial oligarchy (and its collusion with the far-right) without investigating what made it possible is a foolish exercise in political fury. It can appease bitter hearts over successive defeats, but it does not create the necessary conditions to overcome these setbacks.

The 2008 crisis also produced another global political phenomenon: the great political imagination deficit on the left, even though the people showed their indignation time and time again. Between 2010 – when the Arab Spring broke out, followed by the Indignados Movement in Spain and Occupy Wall Street in the US – and 2019, popular revolts against inequality multiplied.

They were almost always gigantic and chaotic, as evidenced in Brazil in 2013. However, the parties that claim to be progressive did not know how to give answers – neither to them nor, more broadly, to the crisis. Faced with this paralysis, the billionaire class swam in strokes.

They won two crucial victories in the political disputes of the past twelve years. The first was to promote, through the mass increase of money supply, a monumental – yet silent – concentration of wealth. Between 2008 and the outset of the pandemic, the central banks of the core players (mainly the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom and Japan) issued, out of nowhere, a volume of money that, according to some estimates, is equivalent to US$ 40 trillion, or twice the GDP of North America.

This immense mass of resources was obviously not distributed equally. First, states saved the biggest banks and corporations – buying mountains of “bad debts”, those that would never be recovered otherwise.

Then, when the economy failed to recover, governments increased the money supply (“quantitative easing”) to at least prevent the ship from sinking, following the “trickle-down” theory. The trillions were created for the holders of public bonds, that is, mostly for the 0.1%.

It all happened without fanfare. Central bank issues don’t require authorizations and the long and exhausting debates in parliaments. But the political effect was dramatic. The banks, whose recklessness had sparked the crisis, were getting away with it. The States that saved them saw their debt explode. They subsequently adopted “austerity” programs that devastated public services.

Thanks to its boldness, the financial oligarchy won the first battle. The issuing of money out of thin air on this scale was something entirely new. However, none of the many left-wing governments dared to do the same in favor, for example, of health, of renewing infrastructure, of fighting global warming or of creating universal basic income programs.

The second battle that the right won without effort was the construction of narratives. Inequalities and poverty increased since the neoliberal turn of the late 1970s. The 2008 crisis accelerated this process. But the leaders on the left – from Barack Obama in 2008 to Dilma Rousseff in 2015 – neither confronted it nor denounced it. They swallowed it.

Someone was bound to claim this political capital that was up for grabs. The movement with the political conditions to do so was proto-fascism. When analyzing the speeches of its exponents – Trump, Bolsonaro, Hungary’s Orban, Italy’s Salvini, France’s Le Pen, Philippine’s Duterte – one can see the repetition of a set of simple formulas, created and improved in right-wing think tanks and then reproduced, with only minor modifications, around the world.

Attack “the establishment” to capitalize on the majority’s just resentment. Confuse them, taking advantage of the low political consciousness of the majorities. Paint the parliamentarian or the qualified public official (whose privileges are exposed in the newspapers) as “the elite”; but save bankers, corporate shareholders, their executives and aggregates (all protected by the silence of the media).

Identify the right-wing leader as the saving hero, able to free the crowds from the tyranny of the “system”. Label dissenting opinions (whether they come from politicians or scientists) as conspiracy theories.

Despite their low sophistication, these narratives were remarkably effective until the outset of the pandemic. The opposition to them was scarce – although successful when it existed, as in the case of Chile. Trump’s defeat marks the possible beginning of a global turnaround. Therefore, it is worth examining it better.

III. How the Pandemic Reshuffles the Cards

Recorded by Bernie Sanders, the video below shows the sign of enormous tactical wisdom – and of the great change of scenery that has become possible in the West in recent months. In alliance with a vast network of social movements, Sanders competed for – and came close to obtaining – the Democratic Party’s nomination for the White House, both in 2016 and in 2020.

He was defeated by Biden in April, following a series of backstage articulations of the party machine, which found his ideas too radical. He lost the battle, but he continued to plumb. Thanks to him and people like Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, most of the movements that took to the streets of his country in June and July, in the protests of the Black Lives Matter, played a key role in the campaign to defeat Trump.

Their actions, especially among the younger and more critical generation of voters, were tireless and extremely effective. Without them, the Democratic Party’s victory in the presidential elections would have been impossible.

But now, Bernie Sanders returns to the stage to remind us that this support was not a blank check. On the contrary: he, who is a senator from Vermont, announced he will present his own agenda for the country “in a few weeks”.

It is the opposite of the political imagination deficit that has plagued the left in the last twelve years – and has the power to shift the center of gravity of the political debate. It includes a wide transition to the logic of the commons: Health as a right for all and no longer a merchandise; student debt relief; the guarantee that any child of a worker will be able to attend university without getting into debt.

It promotes labor logic: fighting hunger wages and facilitating the right to unionization. It incorporates the central ideas of the Green New Deal: moving to a post-carbon economy. This is done by creating millions of well-paying jobs in the public sector, in activities ranging from building railroads to replacing oil with wind and solar plants, cleaning up rivers and restoring original forests.

How could this agenda – so radically opposed to the post-2008 neoliberal “consensus” – move to the center of the political debate, even in the US? To understand it, it is worth looking at the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. From a health perspective, it exposed the falsehood of the right-wing populist discourse.

A recent article by political scientist Chantall Mouffe sheds some light. Far-right leaders need to sell to their supporters the idea that they offer protection in a world marked by helplessness, a crisis of traditional values and insecurity.

But they cannot keep their promise because they are unable to break their ties with the financial oligarchy – and this requires commodification (including health), concentration of wealth, reduction of social spending. The protection agenda, says Mouffe, needs and can be the banner of a new left.

In addition, from an economic point of view, there is a great deal of uncertainty ahead. Since March, central banks have launched a new round of quantitative easing, at an even faster rate than post-2008. In the US, the Federal Reserve has publicly announced it would employ quantitative easing whenever necessary to avoid the breakdown of financial markets (infinite quantitative easing). Flooded with money, stock exchanges rise and rejoice.

But for how long can they stay that way, if unemployment, indebtedness, the collapse of small businesses are skyrocketing all over the West? If a second wave of the pandemic is taking hold across the world? If the programs that guaranteed temporary aid to the poorest are disappearing?

Strange and devious are the paths of the class struggle. Thanks to Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden was elected. But thanks to the election of a conservative Democrat, Sanders’ post-capitalist agenda may be one step closer to taking the center of public debate.

But… what about Brazil?

IV. Will There Be Hope – Even in Brazil?

The astonishing paralysis of the Brazilian left, which until recently was only discussed by a handful of analysts, is increasingly more evident. Ricardo Kotscho, supporter and personal friend of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva for decades, recalled in late October that the Workers’ Party (best known by its initials, PT) shows up at the elections “aged, without votes and without direction”.

Here, it is evident not only a political imagination deficit but also a disconcerting alienation from the reality of the majority. Think of three recent themes – the imminent end of the monthly emergency stipend of 600 reais (about US$ 100), the visible increase in the number of people forced to live on the streets and the sharp rise in food prices.

The left-wing parties have not cohesively promoted mobilizations or denounced any of these issues. This topic is beyond the scope of this article, but it seems evident that the extreme institutionalization of the left in Brazil has distanced it from the real problems faced the population to the point that the left has as its central agenda its own return to power. This is responsible for a good part of the distance – and for the space that has allowed Bolsonaro to continue his criminal trajectory.

Fortunately, the 2020 municipal elections are suggesting that something is changing. Three trends stand out. First, at least in the state capitals, the president has been unable to push his allies to victory.

In two of them – São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro – far-right candidates Celso Russomano and Marcelo Crivella have stumbled and may not even reach the second round. Even in Fortaleza, where Bolsonaro’s candidate had been leading for a few days, has seen a spike in the popularity of the PDT postulant.

The second trend is a sign that candidates from the left and center-left will likely do better than was expected a few months ago. There are clear chances of victory at least in Belém (Edmilson Rodrigues-PSOL), Recife (João Campos-PSB or Marília Arraes-PT), Aracaju (Edvaldo Nogueira-PDT), Vitória (João Coser-PT) and Porto Alegre (Manuela Dávila -PCdoB).

Left-wing candidates have seen significant growth and real possibilities to advance to a second round in São Paulo (Guilherme Boulos-PSOL), Rio de Janeiro (Marta Rocha-PDT or Benedita Silva-PT) and Fortaleza (José Sarto-PT and Luizianne Lins-PT). Chances are slim, but not negligible – especially compared to the disasters of the previous 2016 elections.

Finally, these possible results project the emergence of a more plural and open left. If the prognosis comes true, it will be less subordinate to the centrality of one party, whose bureaucratization has produced so much paralysis. It will also, perhaps, be more open to collaboration with social movements.

If this hopeful hypothesis is realized, the results cannot go unnoticed. Bolsonaro’s likely defeat needs to be celebrated to end the false notion of his unwavering popularity.

And, amidst the risk of a second wave of COVID-19, the newly elected mayors who strive for the common good could – as a counterpoint to the negligence and omission of the federal government – articulate immediate forms of collaboration with each other. It would be even better if they include organizations that symbolize the role of civil society. There are many, for example, in the field of public health.

Changes sometimes bring unforeseen opportunities. It is possible that next Sunday will set up one of them in Brazil. It would be smart not to waste it.

Antonio Martins is the editor of the Brazilian publication Outras Palavras.

This article was originally published in Portuguese by Outras Palavras.