If you go to Minas Gerais, listen to the music. At first, you’ll probably bounce your head to rock, hip hop, or electronic dance music, which is all good. The mountainous Southeast state bordering Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Bahia, Goiás and a sliver of Mato Grosso do Sul is the size of France, so you may have to dig a bit deeper to get a feel for more traditional regional music.

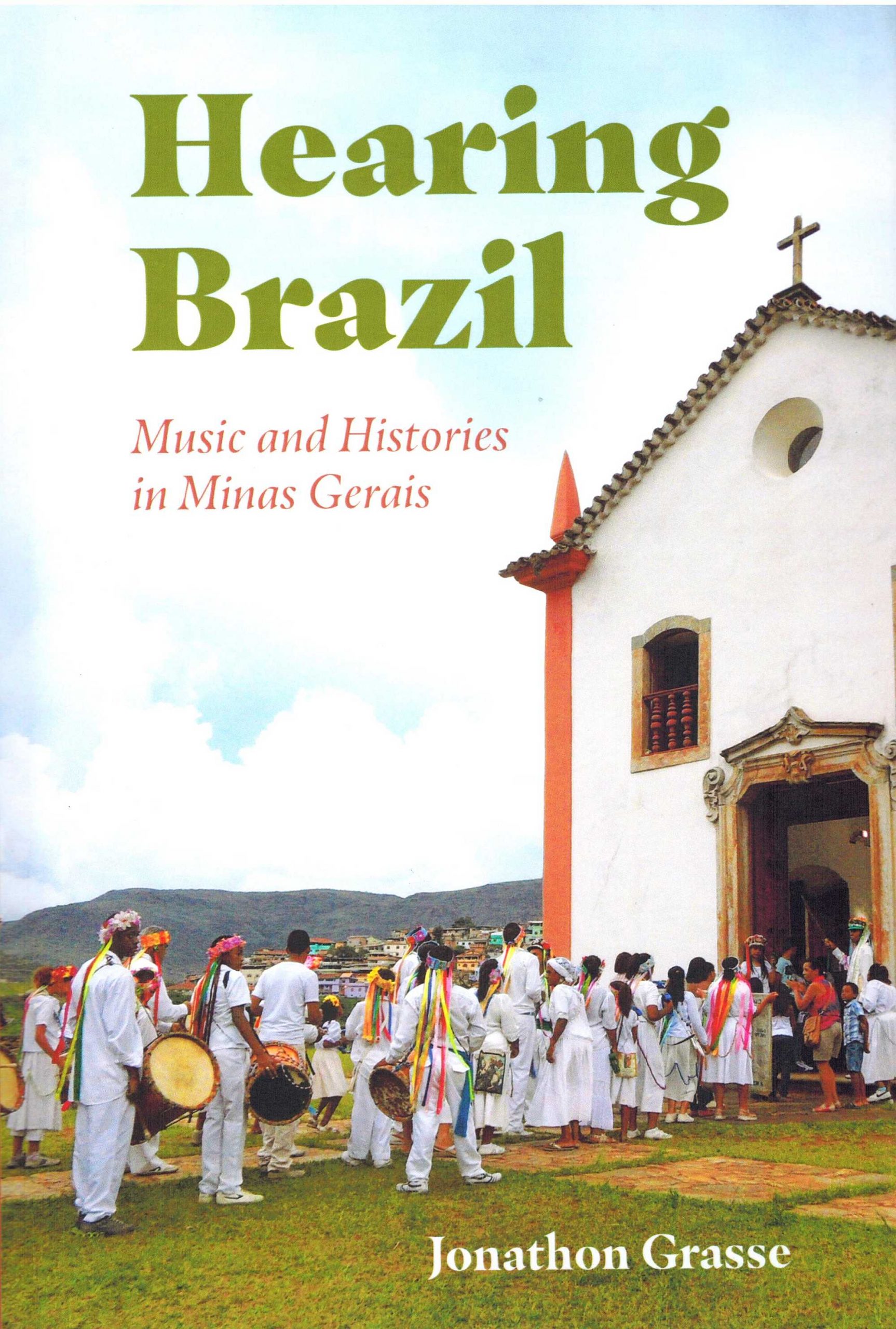

Even if you don’t go to Minas, you can read about its hard-to-find traditional regional music genres in a new book, Hearing Brazil: Music and Histories in Minas Gerais (University Press of Mississippi, 2022). The well-researched volume was fifteen years in the making and draws from fieldwork, interviews, readings and translations from hundreds of Brazilian publications dedicated to regional studies, and those that help trace the culture of Minas Gerais to Africa, Portugal, and back to the indigenous peoples who once roamed here freely.

Emerging from one of the world’s first gold rushes, Minas, as the place is usually called, became Brazil’s most populous state, with booming mining towns and agricultural centers attracting eighteenth-century newcomers even as the colonial period waned and Imperial Brazil dominated the nineteenth century.

Of course, bust follows boom, and the region’s economic struggle continued into the early twentieth century. The big change, however, came with the late 1890s construction of a new capital, Belo Horizonte, taking over from Ouro Preto, one of the region’s many treasured colonial cities. Countless enslaved Africans once mined the gold, diamonds, and gemstones, and now iron is the foremost commodity. Minas Gerais means “General Mines,” and the region has paid dearly for its name.

Hearing Brazil (359 pages) covers a surprisingly wide range of genres with scholarly depth including those lost to history, such as calundu and vissungo. These two Afro-Brazilian music traditions, respectively a trance possession-based religious music and a work song genre once common to secretive mining centers, are joined by two more chapters dedicated to what Americans would consider black music: the popular religious genre congado, and the dance galaxy of batuque also receive ample, chapter-length study.

Congado developed over 500 years, from Portugal’s earliest colonization efforts in central Africa to its growth in Brazil, graces small towns, plazas, and cities alike with its colorful processions consisting of pounding drums and chanted praise songs of a hybrid Catholicism that has absorbed African-related themes and language.

The timeless, African-derived circle dance batuque, known throughout Brazil, also played an important part in regional identity and spawned samba, Brazil’s national dance.

Wealth generated by forced labor mines created lavish churches, filled with music written by regional composers known as the Minas School of sacred music. The beautiful towns of Diamantina, Serro, Ouro Preto, Mariana, Sabará, São-João-del-Rei, and Tiradentes, many protected by UNESCO, boasted a Baroque-era culture full of regional tastes known as the barroco mineiro (Minas Baroque).

Original liturgical music was joined by stone and wood sculpture, painting, and lots of eighteenth-century architecture that still dominate these colonial-era towns and cities. The chapter “Sacred and Fine Art Music of the Colonial and Imperial Periods” also tells the incredible story of twentieth-century musicologists who rediscovered many of these manuscripts and tirelessly reconstructed a nearly forgotten repertoire of original regional heritage.

As Hearing Brazil examines divergent styles in an attempt to capture some semblance of historical regional music identity, its chapters turn to ever broadening topics, such as the viola, the ten-string guitar that has come to symbolize the rustic past of the Brazilian interior. Here, contemporary musicians and luthiers help illustrate the special role a musical instrument plays in conjuring the soul of the vast countryside.

The final two chapters are sort of paired together: a musical profile of the ever-modernizing, ever-sprawling city of Belo Horizonte, and the closing chapter examining the regional themes found in the popular music collective from Belo Horizonte known as the Corner Club. Today, the city’s metropolitan region is home to close to six million, one of the fastest growing urban centers in the world during the years 1940-1970.

The chapter entitled “Belo Horizonte Nocturne: Subtropical Modernism, 1894-1960” focuses on the growth of a bands, classical music, and important institutions dedicated to formal music as well as aspects of Carnaval, the radio years, and other mid-century developments in the city’s music scene.

Throughout, Belo Horizonte is described and examined as an overlooked urban cultural gem of Brazil, with its own history and identity. The final chapter brings readers into what is still a vital, extant popular music developed mostly in Belo Horizonte by a large collective known as the Corner Club (Clube da Esquina), specifically the regional themes in their songs.

Corner Club

A closely related title equally well-researched, takes you to the heart of what has been described as Brazil’s best record ever made: The Corner Club (Clube da Esquina, 1972) by Milton Nascimento, Lô Borges, and many of their friends, a record made by some of the musicians discussed in the final chapter of Hearing Brazil.

Milton Nascimento, this year embarking on his final tour, spearheaded this amazing group of musicians, many of whom are still active as creative songwriters and performers. The Corner Club (162 pages), published in 2020 by Bloomsbury as part of their 33 1/3 Brazil series, tells the compelling, in-depth story of the album, discusses each of its songs, and offers insight into the musicians, places, and challenges in making the record.

Where Hearing Brazil embraces centuries, and many disparate aspects of the region’s music and history, The Corner Club focuses on a double album that helped Brazilians endure the darkest years of the military dictatorship. Here, the Portuguese lyrics and song themes are translated and explained, revealing the powerful meanings of this important popular music, its poetry, and timelessness. This year Brazilians are celebrating the album’s 50th anniversary.

Jonathon Grasse is a professor of music at California State University, Dominguez Hills. For over thirty years he has visited Minas Gerais with his wife, who was born and raised in Belo Horizonte.

jgrasse@csudh.edu