“I would come back to live here if I could,” said Altair Guimarães, plucking a guava from a fruit tree that survived the re-development of Rio de Janeiro’s once-thriving Vila Autódromo community, all but razed by the 2016 Olympics project.

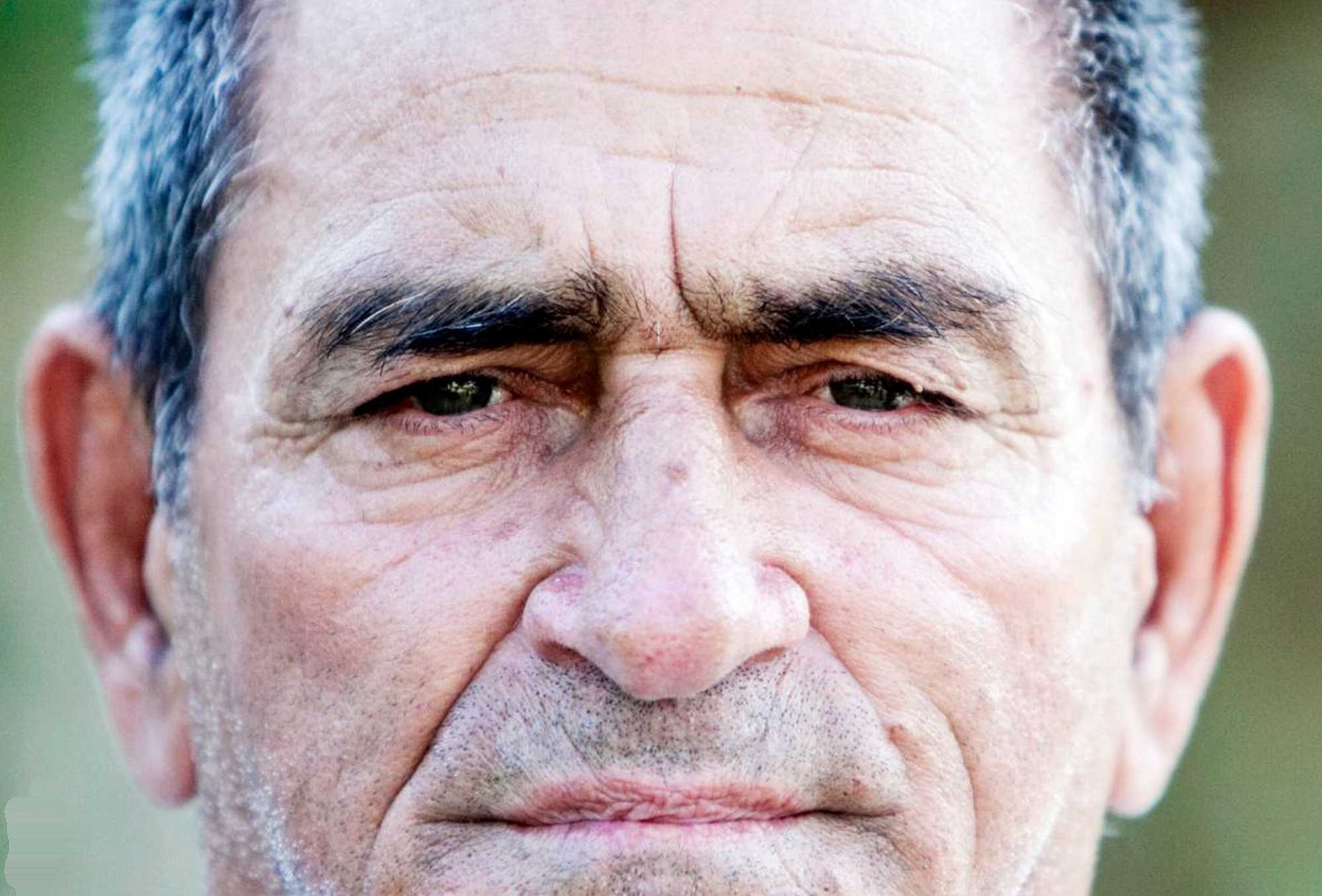

Guimarães, 61, was evicted from his home two years ago and today the trees, a church and two rows of small white houses are all that remain of the neighborhood on Rio’s western fringe.

City authorities allowed just seven families of more than 500 to stay on in Vila Autódromo in the run-up to the Rio Games, a decision that ended a decades-long, sometimes bloody struggle between residents and the police sent to evict them.

For Guimarães, the forced move from Vila Autódromo was the final, bitter chapter in a life-long quest to put down roots in the city of his birth.

Evicted three times over three decades from different parts of Rio, his life illustrates how the re-development and gentrification of Brazil’s second biggest city has pushed many of its poorest residents to the edges, mirroring a global pattern.

Population Explosion

More than a quarter of Rio’s six million-strong population live in 1,000 or so informal settlements known as favelas.

The first favelas appeared in the late 19th century, established by soldiers returning from the War of Canudos, the deadliest civil war in Brazil’s history when the army crushed a rebellion by peasants in the backlands of northeast Brazil.

Later populated by formerly enslaved Africans, the settlements grew during the 1970s as hundreds of thousands of rural migrants moved to the city in search of work.

“If you analyze Rio’s eviction process, there were periods when the poorest were expelled and people were evicted,” said Professor Orlando Santos Junior of Rio de Janeiro Federal University’s Urban and Regional Planning Research Institute.

“There were also periods of acceptance when occupation of informal areas by the poorest was tolerated.”

Rio de Janeiro’s Truth Commission, set up to investigate abuses committed during the 1964-1985 military dictatorship, said one of the most brutal waves of evictions unfolded between 1962 and 1974 when more than 140,000 people lost their homes.

Then governor, Carlos Lacerda, cleared areas targeted by developers, including three favelas on the Rodrigo de Freitas lagoon near the beaches of the city’s south zone.

In 1969, among those ordered to leave their homes and climb into garbage trucks with their possessions was 14-year-old Guimarães whose family’s shack in the Ilha Dos Caiçaras community was destroyed.

The eviction ended an idyllic childhood fishing in the lagoon and playing on the beach.

“Tears were pouring from my eyes,” recalled Guimarães, staring over the lagoon. “I was leaving a place I knew and loved and I was going to live somewhere I hadn’t even visited.”

Turf Wars

Santos Junior said the wave of repression and evictions was particularly brutal during the dictatorship era.

“Areas such as favelas … were subject to real estate interest. Or if the poor communities bothered the middle or upper classes living nearby in any way, you would see periods of eviction and repression,” he said.

Guimarães and his family were moved to the new housing project of Cidade de Deus – or City of God – built on what he describes as “a wasteland” in Rio’s western outskirts.

The lack of infrastructure and isolation, he said, sparked tensions between new arrivals from different favelas, culminating in a violent war between drug gangs for turf.

“What was supposed to be a model city turned out to be hell,” said Guimarães, adding that he often had to throw his daughters on to the floor to protect them from stray bullets.

A builder by trade, he managed to construct a house for his family but in the early 1990s they were targeted for eviction again, this time to make way for an expressway, the Yellow Line.

Guimarães said the second eviction was easier to accept because it was to build a new road “for the public good”.

“Are evictions necessary for development? The simple answer is no,” said Santos Junior. “However, it is cheap to evict – so [they do that] instead of developing a trajectory that respects the right to residency guaranteed under Brazilian law.”

Guimarães was offered a new home in the City of God but opted instead to start again in the tranquil community of Vila Autódromo near the Jacarepaguá lagoon.

“When I went from City of God to Vila Autódromo, I went to paradise,” he said.

However, the family’s time there coincided with the fierce political battle to protect the neighborhood from property speculation and ended in his third eviction.

As president of the local residents’ committee, Guimarães led the fight against former Mayor Eduardo Paes’ plan to build an Olympics access road which would all but destroy the well-established community settled in the 1960s.

Many in the community had property rights and their battle to remain became a potent symbol of the tensions sparked by rapid urban expansion as the world’s media documented clashes between residents and military police sent to evict them.

Guimarães said some families accepted compensation and left while others were forced out and their homes demolished.

“In the end it became an unequal and cowardly struggle because of money. I started to lose the fight [to persuade others to stay] because of the amounts of money they were paying,” he said.

Guimarães, whose family bought a small apartment with their compensation package, said leaving the community was painful.

“You lose your history, your connection to the neighbors.”

The Next Wave

Today, Guimarães still advises Rio communities facing eviction, including Horto, a favela founded almost 200 years ago by workers building Rio’s Botanical Gardens.

A local group has blocked Horto residents’ claim to seek property titles and stay on in their community, citing environmental concerns. The case is before the Supreme Court.

“The case of Horto is symbolic in Rio de Janeiro,” said the residents’ lawyer Rafael da Mota Mendonça.

“If Horto were on the edge of the city, it would be legalized by now, but the local rich don’t want a poor community in the area to be legalized. That’s the main issue.”

Horto’s fate is also seen as an indication of the possible direction of new Mayor Marcelo Crivella, who has said there will be no evictions on his watch. Under his predecessor, Paes, around 22,000 families were evicted ahead of the Olympics.

Rio’s new Municipal Secretary for Urbanism, Housing and Infrastructure, Indio da Costa, said it had been wrong to move people far from their communities in the run-up to the Olympics.

“For me, what they did was a crime because you cannot remove a group of people and put them 30, 40 km away from where they lived for a long time,” he said.

“Of course, if you need to remove, you need to put them next to the place where they used to live.”

A new law to regularize land that was introduced by Brazil’s President Michel Temer in December has made it easier for Rio to distribute property titles and would accelerate the process, he said.

Santos Junior said all future urban redevelopment plans should include formal consultation with residents.

After a lifetime of being uprooted in his own city, however, Guimarães was skeptical about change.

“I would like to appeal to all the world’s rulers that before they remove people, they take into consideration the human being,” he said.

To see the full film – http://news.trust.org/item/20170424122641-5kg1o/

This article was produced by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Visit them at http://www.thisisplace.org