Brazilian black movements have been organizing and protesting against racial violence and injustice for decades. When the Black Lives Matter movement became a global force, activists in Brazil adopted the rallying cry to bolster their own historical fight.

In July 2016, the month before the Olympic Games, US delegates from Black Lives Matter traveled to Rio de Janeiro for what became known as ‘Julho Negro’, or ‘Black July’ – a conversation between leaders of the movement and local groups working to highlight issues such as escalating police killings and militarization in Brazil (particularly in the favelas); the continuing incarceration of black youth; and the racist structure of the state, based on centuries of exploitation.

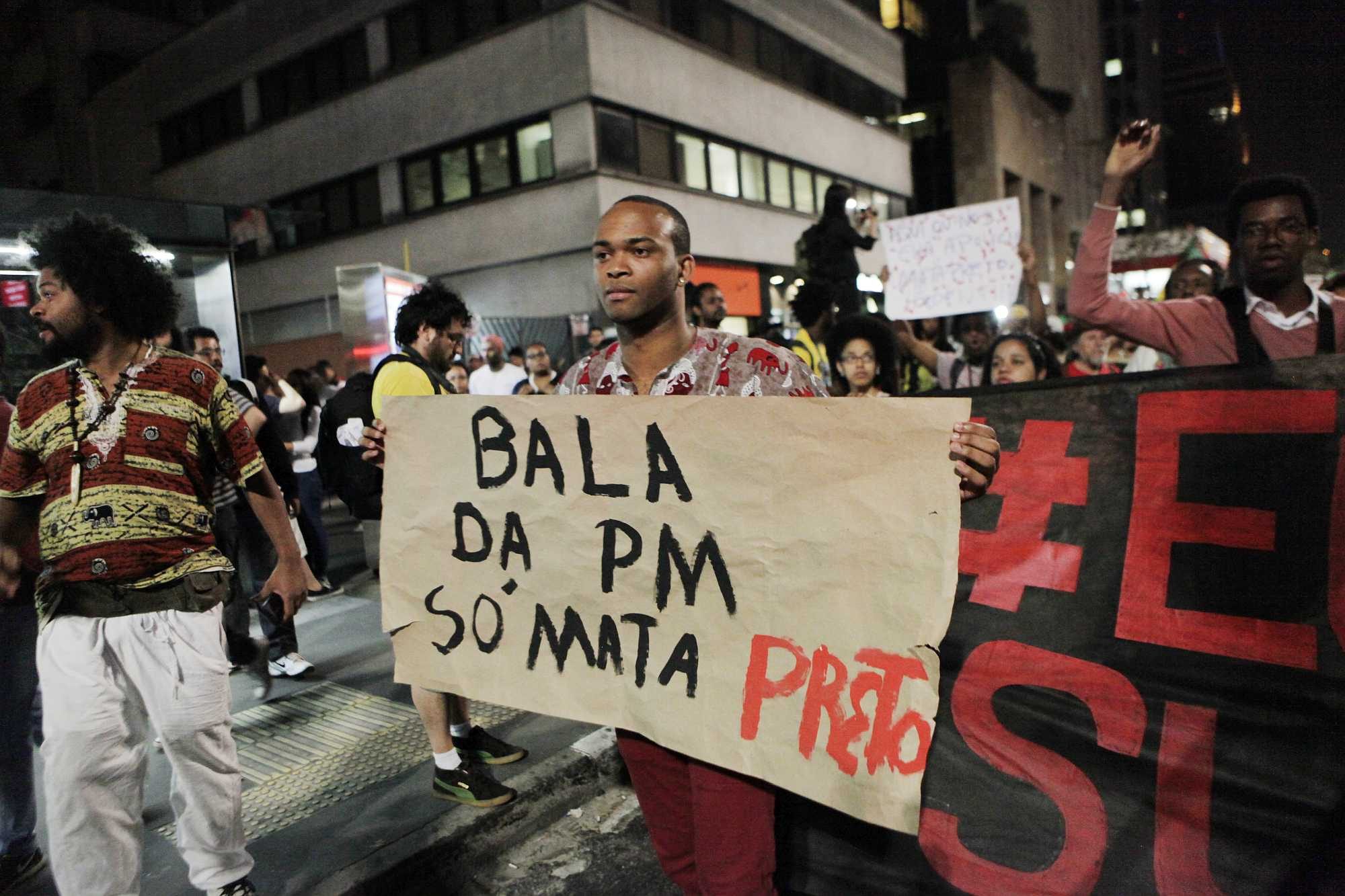

Brazil’s black movements continued to grow in 2017, with numerous protests in São Paulo, Rio and elsewhere. Here, Brazilian sociologist Tulio Custódio describes the black experience in relation to revolt and resistance.

Abdias do Nascimento (1934-2011) was one of the leading black intellectuals in Brazil. He was active in theater, art and politics. His life was marked by activism and he managed to reconcile creative activity and political thinking.

In 2006, sociologist Antônio Sérgio Guimarães published an article clarifying the notions of revolt and resistance present in his own thinking as an academic.

The article showed how revolt and resistance have been fundamental to breaking free from the logic of racial democracy and allowing the development of a questioning perspective in black culture.

In what sense are these two notions relevant today as we witness the emergence of movements like Black Lives Matter? What are the effects of racism on the experience of the black Diaspora?

We can look at it from two dimensions: material and subjective. From the material, objective perspective, the situation of black people is marked by racism as the basis of political and economic power: the exploitation of black labor, the objectification of black bodies, the trauma and the death of black people.

This material situation is what can be seen with the naked eye, in the black bodies lying on the ground, begging, in our big cities, abused by the repressive power of the state and imprisoned in unequal proportions: leading the statistics of violence, vulnerability and mortality.

On the other hand, when seen from the subjective perspective the effects of racism are less obvious, but are nevertheless extremely important.

As philosopher Cornel West points out, it is necessary to go deeper to find the despair, the burden that’s carried, the collapse and the loss of meaning of black life experience.

He calls this experience – which includes psychological depression, lack of self-value and social despair found in all black communities – “black nihilism”.

Nihilism has to do with the experience of leading a life with no meaning, no hope and no love. It is an experience of living in humiliation and moral devaluation.

Integration into the capitalist system did not heal the scars and wounds caused by racism. Market ethics replaced the associative (and protective) traditions of black communities.

The beliefs and images of white supremacy assail the intelligence, the skills, the beauty and character of black people daily, in subtle and not-so-subtle ways.

Without hope there is no future, without meaning there is no struggle. Existential anxiety heightened by nihilism is the historical experience of blacks before white supremacy.

In so far as it denies hope, black nihilism transforms anxiety into rage, into black-against-black violence, the main victims of which are black women and children. These are the adverse consequences of this process.

That lived experience is externally stamped on blacks as being NOBODIES, as Marc Lamont Hill explains in his book Nobody: Casualties of America’s War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond.

Being a NOBODY is being vulnerable. It is to be subject to ordinary violence by the state, to daily terrorism and to the injustices of daily life. It is being abandoned by the state and being considered disposable.

We know that the cumulative effect of wounds and scars is anger and rage. And it is that anger that is captured as a transformative energy for action.

That diagnosis can be called, states Cornel West, Niggerization – a process that transforms black individuals into Nobodies. Niggerization is a process that can even be “transferred” to other social groups, for it means “being insecure, unprotected, subject to random violence and hatred” – which are all direct consequences of a continuing process of nihilism and structural racism, which leads to the hopeless acceptance of domination.

Thus we come to the relevant concepts of revolt and resistance. Against nihilism and Niggerization there exists a power that turns into revolt. Subjectivities and historical collective memory try to fight back against the process of Niggerization.

In the tradition of black thought, there is a special place for this rage, as Audre Lorde points out: “My response to racism is rage: rage over exclusion, rage over unquestioned privileges, over racial distortions, over stereotypes, betrayals and cooptation”.

Lorde, like other black thinkers and leaders, presents us with the challenge of turning rage into transformative energy – so that rage becomes revolt and rises as a form of resistance against oppression and nihilism. Rage becomes power for change, it becomes revolt as a form of transformation and resistance.

Abdias do Nascimento incorporates the notion of revolt from the works of Albert Camus: “What is a revolted man? It is a man who says no. But while denying, he however is not renouncing: he is also a man who says yes from his very first move”. That move is the organization of revolt, which allows for protest.

Let us now go back to the notions of revolt and resistance. The richness of the concept of revolt (or “revolted being”) is that, almost as a traumatic shock, it describes a movement that contains the possibility of insurgency for existence, for action. If conscience is born out of revolt, it is from that movement that black revolt arises.

By turning rage into energy, the revolt is transformed into the essence of freedom. For black revolt is about liberation. As Abdias says, “the revolt is the result of a lucid, well-informed conscience that does not compromise or make any concession with its identity and its rights”. The value that a black person invokes when revolting is his value as an individual, his value as black, his value as a citizen.

The Black Lives Matter insurgency against state violence is an ideological and political intervention in a world where black lives are systematically and intentionally considered an object of failure.

It is a statement of the black people’s contributions to this society, of our humanity and our resilience to deadly oppression. It is not a “moment”, it is a “movement”.

All this can be seen today as we witness the surge of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The concepts of revolt and resistance as ways of turning rage into transformative energy and resistance against the genocide of black people are at the core of the Black Lives Matter movement.

It is a form of insurgency that is a form of resistance – for life, for a life that matters, for lives that matter.

Tulio Custódio is a Brazilian sociologist, knowledge curator, founder of Pitacodemia and a member of Black System Collective. He writes in a number of media on inequality, racial issues, capitalism, technology and gender (masculinities).

This article appeared originally in Open Democracy https://www.opendemocracy.net/