With a population of more than 2.5 million, Manaus is by far the largest city in the Amazon. As such, it reminded me of a large wet Alice Springs – situated also, in human terms, in the heart of nowhere. However, Manaus is the nerve centre for trade routes which run for hundreds of miles, routes which overrun borders and connect the peoples of Colombia, Peru and Bolivia via the jungle’s watery highways. From this Amazonian capital, I booked a three-day tour into an interior that makes up over half of the fifth largest country in the world.

Many come to Manaus by boat from the Atlantic port of Belém. The 850-mile journey upstream takes up to five days. A friend took the slow boat some 15 years earlier and almost died en route when he came down with a severe infection. It was (falsely) reported as cholera in a local paper. It was a big story as it concerned a foreigner and the Chinese whisper filtered through to the European press. The stories of other voyagers seemed mixed; one person’s idyll was another’s endless hell. The romance of the old ways was understandably lost on those placed centre stage to mass outbreaks of diarrhoea on boats with limited toilet facilities and no escape from the heat and humidity.

With its frontier town ambience, Manaus was not a city to gad about. The guidebook warns visitors away from the docks through which the messy trades of the Amazon have flowed long before the airport and the tourists arrived. The travel agent from whom I booked my trip was a gregarious type, a throwback to an era where he might have roamed the territories rather than selling their charms to outsiders. He offered me rum, to numb us from the stultifying wet heat that the ceiling fan was buffeting back at us, before advising me to buy a street-side coconut for my upset stomach. It had cured me by nightfall.

I spent the afternoon wandering around the centre – a bustling, hot working city with few obvious attractions. Strangely, Manaus boasts a world-class opera house, the Teatro Amazonas, which attracts more fat ladies and gentlemen than you expect to find singing in a jungle. Built in a renaissance style from money earned from the late 19th Century rubber boom, the music hall might have been slipped into its incongruous central spot by a mischievous giant. In its early days, a visiting company of opera singers lost half their chorus to Yellow Fever.

The city declined after the rubber boom, before reviving as a free-trade zone, and more recently, a hub for ecological tourism. (By 1910, rubber had rivalled coffee as a Brazilian export following the invention of vulcanisation by Charles Goodyear. Its population grew from 5,000 in 1848 to 70,000 50 years on. In 1913, Far Eastern production reduced the price of rubber to a quarter of its rate of three years earlier. After half a century, Brazil was reduced to importing it.)

The Heart of Darkness

Early the next morning, we chugged downriver in the rusting hulk of a motor-cruiser. From docks bustling with traders, the rush-hour traffic ran for hundreds of miles in every direction. After 15km, we entered the Meeting of the Waters – a 6km stretch in which two rivers – the Negro and the Solimões run side-by-side without mixing before combining into the mighty Amazon. The former, with sources in Colombia and Venezuela, is light brown and thick with mud, while its more salubrious blue partner flows down from the Peruvian-Brazilian border.

Grey and pink dolphins grace the waters. Pink dolphins are endangered due to pollution, collisions with boats, and the mindless use of their flesh as fishing bait. Swimming tours with pink dolphins are thought to influence their behaviour unhelpfully though some conservationists argue that it enhances their perceived value and thus reduces the numbers slaughtered.

Meanwhile, harpy eagles with talons the size of a grizzly’s are likely to be watching from the shoreline with beady fearless eyes. The eagles have no predator beyond humankind so their traditional position at the top of the food chain makes their fearlessness a weakness to hunters, while loss of natural habitat has further diminished their numbers.

After several hours, we moored alongside a long hut on stilts wedged onto a muddy bank. Untamed jungle sprouted up all around. Similar outposts poked out gingerly from the mass of foliage every few kilometres like Heath Robinson structures from old Tarzan films. Most are fitted out for tourists of all budgets. The wealthier guests sipped cocktails on high platforms outside private rooms.

By contrast, our riverside floating cabin consisted of a long wooden room lined with hammocks. A small kitchen lay at one end. The mesh screens that filled the window spaces allowed the light in while keeping the larger insects out. For all the dog-eared postcards plastered in the windows of the travel agencies, the myriad species of indigenous monkeys and birds are heard but rarely seen along with three quarters of the planet’s creatures. But if the fauna is generally reclusive, we spent most of our time on land being lectured on the medicinal properties of the flora. We canoed around lily pads several metres wide that looked sturdy enough to hold several corn-fed children.

I pretended to see camouflaged primates spotted by our excited guide, while the long lens of my camera wasn’t quite long enough to make out the wildlife scampering above our heads. While the monkeys and birds flitted about the periphery of our vision, the zoo is the only place you’re likely to see jaguars – the mysterious big cats that are a symbol of the continent and the retiring kings of the jungle.

Caimans were more plentiful, but also largely unseen. On one night paddle, our guide plucked a hatchling from the riverbank – identified by the torchlight reflecting eerily off its distant prehistoric glare. This young member of a family that has endured 200 million years was an eight-inch microcosm of the adult, stripped by diminished scale of its terrifying aspect. His mother, our guide reckoned, was probably cruising the deep water nearby leaving its latchkey charge to fraternise with frivolous floating bipeds. (A fellow tourist in the region told me how his guide – clearly not a health & safety jobs-worth – had paddled blithely amongst fully-grown crocodiles that might easily have gobbled them up after tenderising them with a crash of its powerful tail.)

A tiny frog glaring a vibrant green was attracted by my milky foreign flesh. From some lonely lily, he hitched a ride and placed his destiny in my hands. I tried to re-introduce him into the wild, but he kept hopping back onto my leg, his head perhaps turned by the serendipitous opportunity to leave the conformity of his green world. As I left him on the jetty, his little eyes screamed betrayal.

Exotic animals are more often found in the arms – or at the end of a rope – of the locals. These photo-calls took place on the floating shops that magically appear around bends in the river manned by friends and families of the guides. Complementing the jungle wares were snakes, sloths and monkeys – all presented for our photographic pleasure. It was 20 minutes before the sloth’s neck had swivelled sufficiently for the money shot.

The waters rise and fall with the seasons creating unrecognisably different horizons. With a 14m drop, our floating cabin would be converted to a tree house if its position was fixed. Beneath us, rather eerily, giant anacondas were likely to be lurking – much as the timid but formidable jaguar was perhaps watching from the bough of a nearby tree.

Our dinner generally lay in the invisible deep. The biggest fish in the Amazon are the Arapaima – known locally as Pirarucu – and grow up to 3m and 220kg in weight. Relative sprats turned up on our table to feed a dozen of us.

We went piranha fishing. These collectives of razor-toothed predators make up for their lesser bulk by force of numbers. Our rods consisted of sticks with gobbets of meat hooked onto the end of a string. The dozen strings on our trio of dug-out canoes twitched incessantly like a hungry orchestra at sea. Except for mine – I didn’t catch a tadpole. The gentle tugging on my aquatic divining rod was repeated every few minutes, but each ‘catch’ revealed only a bare mocking hook. Around me, the piranhas ate well. Even odder was how little we thought about their abundant numbers when we cooled off in the same patch of water ten minutes later. Perhaps I’d fed them too well. Our guide explained how their blood-lust makes it advisable for menstruating women to skip the pre-prandial swim. For some reason, he only told me.

Bedtime was my first experience of sleeping in a hammock. A nice idea. I was too accustomed to city life where I dimmed my internal lights with sleeping pills and exhaustion rather than the signal of the departing sun. I watched the guttering lamps burn out to the soundtrack of hoggish snuffling and snoring.

Till dawn made an unwelcome return, I sweated steadily in and out of consciousness. Bar the quiet hum of the generator, the gentle creak of the cabin, and the occasional phutting of a passing boat, human activity gave way to the pitch and tempo of the mysterious nocturnal ensemble.

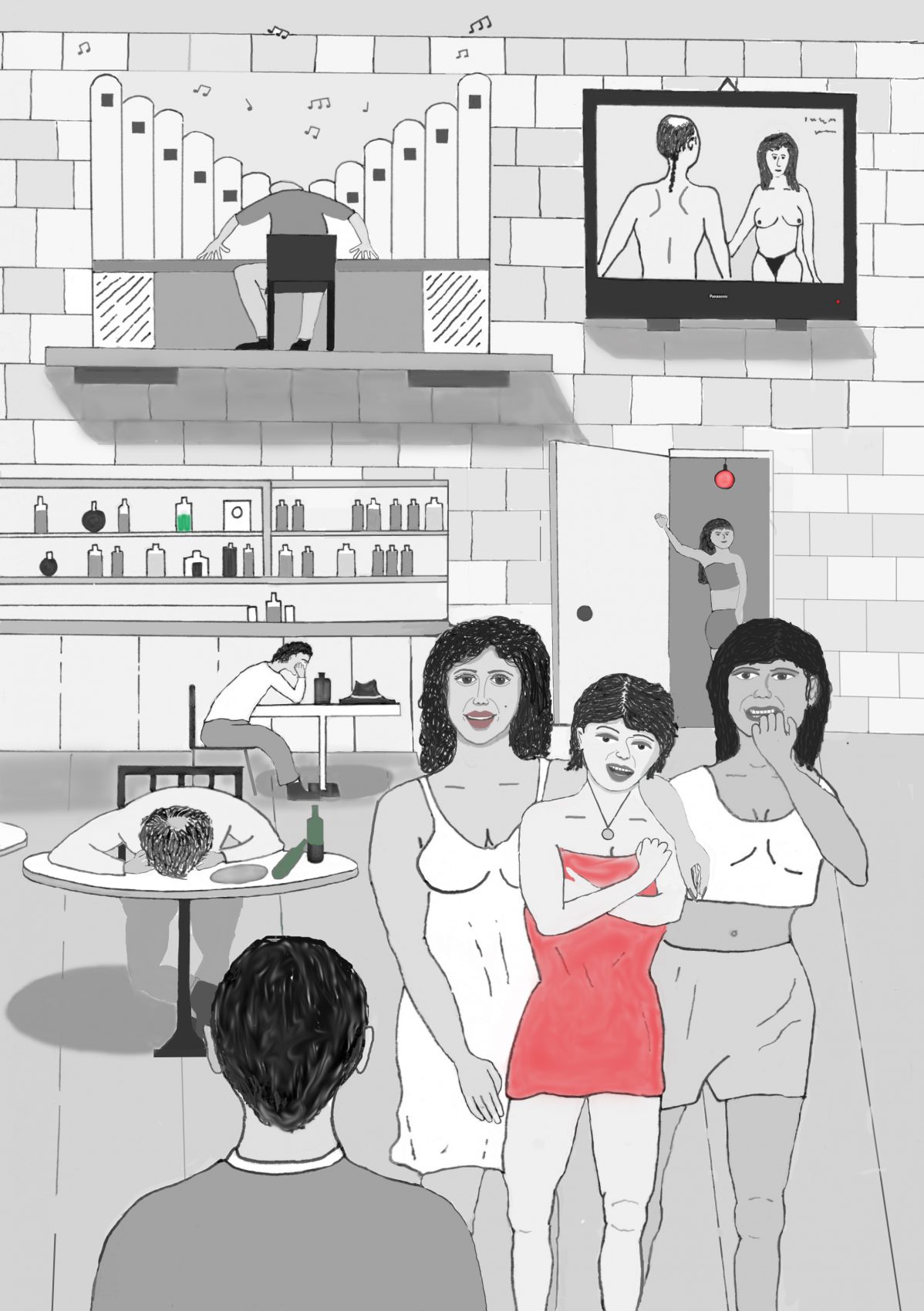

Before flying out of Manaus, I visited some dockside bars with a Dutchman named Paul. We found one in a corrugated iron shed the size of a small warehouse. Inside, cheesy Latin disco blared out of giant distorting speakers, where gentle lift-music would have easily masked the clinks and mumbles of the sparse lugubrious clientele. A handful of the 50-odd tables were taken – several by customers snoozing chin deep in deltas of beer. Bored fading ladies of the night drank alone, sipping away the idle hours before the boats came in.

We moved next door where the relationship between natural and manufactured sound was less extreme, and conversation possible. The infrastructure was similar, but the working girls younger. If the women in the first bar resembled mothers of a certain age, most of the girls in its neighbour were barely in the foothills of adulthood. Messy attempts were made to fossilise their youth under thick layers of makeup.

When I returned from the toilet, a giggling cluster cooed and winked. I smiled back shyly, briefly giving into the daydream that an entire gaggle of nubile women was flirting with me. But deep down, I understood my viability as a potential punter. Unlike most of the barflies, I looked sober enough to climb the stairs to a nearby boudoir.

Rather strangely – perched on a platform 20ft above the bar – sat a bedraggled man hunched over a pipe organ, the like of which might have graced a cathedral. But this cathedral sported hard-core porn on screens flanking its pulpit. The organist’s posture was less classical musician than creature from The Muppet Show. It was hard to say how long he had been there. No obvious route up presented itself. Marooned and forgotten, he now played only for himself.

Fifty Shades of Black

Salvador, Bahia

Salvador offered another contrasting perspective of Brazil founded largely on the tribulations of the ancestors of its largely black population.

Making my flight there was a close-run thing. Just minutes before my plane flew out of Manaus, some unconscious instinct woke me from a beer-soaked slumber in an empty passenger lounge.

Salvador is the capital of Bahia state, but once ruled over all Brazil. This was prior to Rio taking the reins of government, which in turn handed control to Brasília in a bid to run this vast country from a more central point.

(My feelings for Brasília are prejudiced by the $50 taxi ride in which I toured the city to pass a few hours when in transit between my later journey from Salvador to Rio. It confirmed – as if I didn’t know – that a fair price is rarely negotiated after the event. Despite the cost, and my not understanding a word of my driver’s commentary, it was an instructive ride visually. The city’s curiously inverted design places all the buildings of state in its centre while the hustle, bustle and grime of commerce and normal human activity takes place beyond these largely deserted and sanitised spaces. The architect Oscar Niemeyer deliberately created the heart of this modernist city to look like an airplane, which fittingly, can only be appreciated from the sky.)

From Salvador’s airport, I headed straight for the UNESCO-protected old town, Pelourinho. It is the bright spot in an otherwise drab city and a living monument to Salvador’s dark historical past. Perched at the highest point of the city, it gazes down on the lower portion from a precipitous cliff-top. Its cable car saves a long walk. Beyond a bay extending across 1,000km lie 38 islands. More slaves were shipped here during the 16th Century than anywhere else on earth – the darker skins of today’s inhabitants and the largely undiluted African influence on its culture signpost these distant roots.

The region was dubbed ‘Africa in exile’ with many of the estimated 10 million slaves worked the sugar cane plantations of the north-east. Cheaper competition elsewhere led to the industry’s demise. The once fertile land was despoiled and most of its cruelly stolen workforce left destitute. From this point, an estimated half million died from droughts, diseases, and the long trek to the Amazon for work in the booming rubber trade. Industry in the region later revived in response to the growing North American taste for chocolate, but the monoculture of cacao – as with the sugar-cane it replaced – has proven equally sensitive to price drops elsewhere in the globe.

~

Narrow cobbled streets run off the main squares of Pelourinho, which are bejewelled by ornate colonial churches and museums. The huge ceiling of São Francisco Church and Convent is overlaid in extravagant gold leaf designs, while the Igreja de Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Pretos (The Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black People), built at night by slaves, houses wooden effigies of black saints. The profits of the plantation owners were ploughed back into such projects – smokescreens to the plunder and suffering that paid for them. While these churches are the main tourist attractions, it is Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian religion performed with elaborate ceremonies, dancing and drums, which commands a thousand dedicated temples.

At sunset, the cafés and bars around the old slave market wake from the slumber of its daytime siesta. The grey ghosts of history were lost amid the bright noise and fanfare. Bands packed out the squares. One evening, I saw Olodum, a carnival drumming group, which found international fame on Paul Simon’s Rhythm of the Saints. A heavy police presence loomed about the plaza in watchful anticipation of trouble from the gangs associated with the music. Whipped up by the thunderous martial roar of the drums, the mood felt tense and threatening as if drawing on the dark rumbling echoes of the past.

During Carnaval, Salvador trails only Rio for visitors. Even natives of Rio confess it’s wilder in Bahia. Tens of thousands venerate the saints by day before dancing till first light on the beaches. It was Tuesday night when I arrived. Wandering about the craft shops, bars and eateries of the close, cobbled streets, I met, without trying, half a dozen locals wanting to share a beer. And soon, I heard the first drums. By nightfall, the quarter reverberated to the pounding of hands and sticks on hundreds of drum skins. Each group, towing mobs of swaying tourists like percussive Pied Pipers were swarming about the narrow streets facing off rivals and competing for a greater following. By sundown, bands popped up on stages dotted all around playing strands of samba such as the home-grown Axé, which fuses elements of Caribbean music such as reggae and calypso with Brazilian influences.

I followed these hypnotic snakes of humanity for several nights. Eventually I began to question the point of shuffling around in a circular pattern indefinitely. Once, within the bustle, I trod on a local’s foot. Her grimace of pain hardened into a glare of pure hatred, with which she trailed me with wordless reproach for the next hour. My apology appeared redundant. A small accidental gesture set off a chain of deeper resentments symbolised by my stranger’s face. Pursued by this unforgiving Fury, I struck off into the crowd.

I befriended Ron – an Israeli from my hostel – a fleshy man in his late 20s with a fluffy brown beard and a Periclean mien of studied thoughtfulness. ‘Befriended’ is perhaps a bit strong. He travelled alone, away from the separate stream of life often occupied by his compatriots. He had little allegiance to anyone – relatively indifferent to the company of strangers of any hue.

Ron’s modicum of charm was reserved for womanising – a pastime he treated with the cold professionalism of an elite sportsman. One evening in a bar, I observed him slowly wooing a well-groomed and sophisticated young woman. When he finally whispered his seductive coup de grace, she agreed to leave with him – for $30. She left him apoplectically alone, while I struggled to sympathise with a straight face. Days later, when I bid him farewell, I offered my email in case he was one day tempted to visit London. His response was typically terse and unsentimental. ‘There’s no point, I won’t come.’ It was a friendship of sorts, but not one compromised by a mote of intimacy.

Sex, carnaval and football were woven into the weft and warp of everyday life. It’s not surprising that sex follows the tourist dollars and the industry overflows from the clubs and designated areas into the street-life. On my first night, a woman materialised into my arms at the door of a bar – the tableau a heaving melding of Brazilian and European life at play. My unsolicited partner was a skinny black girl who looked no more than 15. She signalled to her team-mate to grab another lone male threatening to slip their unsensual clutches. For a verse of song, she clung to me, limpet-like, swinging me awkwardly back and forth with sharp jerky movements in some cold mechanical echo of salsa. I commented with forced good humour on how friendly the locals were while gently disengaging myself and striving towards the bar.

‘You gay!’ she snorted contemptuously after me, and a little unfairly, I think, addressed to a man politely declining the services of a prostitute. Just English.

If the drums don’t get you, the berimbau will. This one-stringed instrument twangs the rhythm of another local institution: capoeira. A melding of dance and martial art, it was created by African slaves to resemble the former, while allowing fighting skills to be passed down the generations under the noses of the Portuguese masters. Many slaves hailed from Angola and this word became synonymous for both displanted Africans and this style of capoeira. Bahia is its spiritual home, and Salvador the destination of pilgrimage for more worshipful practitioners. On a foray to Salvador’s beachfront, I witnessed small groups of men rehearsing in the sand – the first evidence that it didn’t just exist in the distant past or the more culturally diverse gymnasiums of the developed world.

While training as a broadcast journalist, I made a short film about it with my classmate Keme (who later increased his audience somewhat as a reporter on Channel 4 News). We filmed some classes and I enrolled for a few sessions to add material to our film. Like tai chi, capoeira’s emphasis is more on perfecting sweeping and graceful moves than terminating arguments with extreme prejudice. Nonetheless, it has a fearsome reputation in the hands and feet of its masters – various exponents of the Mixed Martial Arts franchise draw heavily on its skills. They tend not to be confused with dancers.

My patience had soon dissolved after laboriously repeating the same leg sweep for a long half hour. For those persevering, agility in the form of elaborate handstands is one of capoeira’s hallmarks, and one tutor I met did an impressive head spin too. Small, dark and dreadlocked, Oscar found his way to Brixton via the beaches of Salvador, where he had first studied capoeira as an eight year old. Crammed into a room in a South London leisure centre, a hotchpotch of sprightly Brixton folk crashed about the mats with varying degrees of co-ordination and success. Oscar taught by happy example.

A more po-faced exponent was an English instructor called Simon who gave us the quotable if rather dramatic soundbite that ‘capoeira is my life’. A short crop of red hair surmounted his pale English complexion suggesting he would probably stick out in an identity parade alongside the traditional masters. Simon practiced capoeira with the zealous dedication of an outsider seeking to break into a hallowed inner circle. Understandably, his methods were more textbook than culturally acquired. The class began with his students dizzily circuiting the hall before meeting in the middle to beat long thin sticks together in synchrony. Minus the bells, it resembled the first rehearsal of a Morris dance. The budding street fighters of the estate were perhaps otherwise engaged.

Simon had elevated capoeira to a religion. The humble berimbau gamely aped the roles of the more expansive organ and choir. For a mitre, a woolly hat graced the crown of his head. He believed disciples should make a pilgrimage to Salvador at least once in their life to learn at the feet of the masters. Amongst other acts of faith, he loftily informed me, one should learn Portuguese. This seemed rather onerous but I asked, off-camera, how well he spoke it. He confessed, rather more humbly, that he hadn’t really mastered the language, but knew enough to catch a bus.

In my next Brixton class, I asked Oscar if this was really necessary for an education in capoeira. His rarely furrowed brow creased briefly before he dismissed the idea with a curt ‘No’, sprang backwards in a swirl of feet, and landed on his head. He remained there until the end of our conversation.

A New Yorker practiced capoeira in the narrow corridor outside my dormitory in Salvador each morning. His monkish serenity seemed something of an affectation and his outstretched body blocked anyone from using the lavatory. Like the falling tree in the forest, he gave the impression he wouldn’t be practicing his moves if he wasn’t being watched performing them.

All about Pelourinho, the berimbau echoed from the classes of the residing masters, who no doubt struggled from time to time to keep straight faces as the possible descendants of the slave owners reverentially murdered the moves created by the slaves two centuries ago. The overnight break between the drums falling silent and the first twangs of the sunrise berimbau was about two hours.

~

In Brazil, the potential for violent encounter always felt one wrong turning away. Pelourinho may have been the polished jewel of the city, but the police who patrolled it couldn’t stem the osmosis of poverty from the city beyond. Street kids regularly popped up at my elbow – their eyes glazed from the glue-sniffing that kept them in a parallel alien world to the crowds of foreign revellers they circled around. As night fell, away from the tourist sanctuaries, I felt a palpable tension walking among the masses amongst this nation of famously gregarious folk.

Outside a bar one night, a child of seven or eight came to the table where I was drinking with a group from the hostel. He took a strange dislike to a sweet-natured young English woman by punching her hard on the arm every minute or so. His childish features contorted horribly towards this random object of hate. The waiters turned a blind eye as if unwilling to call out one of their own. Our only solution was to place ourselves protectively between the two. Buying street-kids a protein drink, it transpired, was one positive response to bridging our two worlds – if unlikely to quell the deeper anger of this one glue-addled kid whose childhood had gone missing along the way.

Otherwise, the locals stood out for the infinity of skin shades that coloured them. Compared with the south, Salvador is very much Black Brazil and the spectrum of shades was evenly spaced with no obvious sense of social division between them.

~

Foolishly for a bad sleeper, I stayed in a dormitory. I remained ignorant of nearby hotels offering private rooms for the same money. A procession of wilting revellers returned to the dorm throughout the night.

One dawn, an incoming Dutchman incurred the wrath of the slumbering by chatting loudly to his companions and switching the light on and off – seemingly oblivious to the presence of half a dozen room-mates. He largely ignored our tuts and grumbles – a habit possibly developed in tandem with the growth of his muscles, which were impressive enough to fight off mythical monsters. Sculpted like an archetypal Hercules, or Tarzan, – as it turned out he was known, his broad back was etched with an expansive tattoo that changed form and meaning when the rolls of muscle flexed. A gaggle of teenage Brazilian girls gathered gigging around him in the corridor the next morning awed by his comic-book physique.

My unfavourable first impression soon changed. Aside from his dubious dormitory etiquette, he turned out to be friendly, thoughtful, and shy. He was travelling with his garrulous big sister and her boyfriend, whose contrasting girths and relaxed smiles promoted a less punishing path to happiness. Tarzan lived a quiet single life in the same home town as his sibling. If I needed a bodyguard, I’d hire him.

The hostel was a vibrant meeting place to befriend a motley crew of ages and types. Most were fellow tourists – the intractability of the Portuguese language creating a barrier with most locals while welding the Anglophones together. Another Dutch brother and sister I met experienced the best of both worlds having learned Portuguese during a childhood in Mozambique. Their translating skills were much in demand along with their customary national gift for speaking the rest of our European languages.

When we met, the brother was whispering sweet somethings to a sweet and demure young Salvadorian woman, Sophia, before his imminent departure home. Sophia suggested a drink when we bumped into each other a few days later. In what way she liked me, I’m not sure, but my friendly greeting may have been misinterpreted as something more significant. It wasn’t something more significant mainly because our conversation was limited to Neolithic basics. The capoeira-practising New Yorker from my hostel rolled up, along with a young compatriot. The latter had the air of one who could remain contentedly himself in any surrounding. He seemed wise beyond his few decades, while retaining the open warmth of the American character. Fleetingly, I experienced a meeting of minds – one of those rarefied passages of time when amid the crowds, you cross paths with one who sees most of what you do.

But here, both Americans thought they were interrupting a romantic liaison. Capoeira Man, nonetheless, moved in with a series of chat-up lines of Stilton-like cheesiness. He leant across me towards her, enunciating his English as if to a small, stupid child, while pawing at her with a lack of dignity that was both appalling and hilarious. She appeared rather nonplussed. I should have been grateful for the diversion, but was irritated by his flagrant attempt to chat someone up he thought I was romancing. And to do it so badly.

The Young American half understood the situation perfectly. ‘I’m sorry about that – he was really out of order,’ he later commented consolingly. He had picked up on my irritation, but not for the truth that I’d rather have gone home than be cuckolded over someone I wasn’t pursuing. Democratically, the three of us walked Sophia home, which was at the top of a steep hill some distance from the bar. We shook her hand goodnight. Even Capoeira Man, who had by now given up on the chase. Sophia looked vaguely amused at the surfeit of attention. The next time I saw her, I waved cheerily without stopping.

~

One night, a bright young Englishwoman invited me for drinks. Lizzy was the social butterfly that enabled a mixed bag of us to hang out when otherwise we might have scented our dangerous differences and warily stayed apart.

In the bar, her friend Margaret insisted on talking to me in French, which is what she became when drinking. Margaret was from Surrey, but most insistent that French was the language of love.

‘Ne pensez-vous pas que le français est la langue de l’amour?’ she cooed across the table… again and again for an hour or so. It was certainly the language to disguise slurring, and despite my efforts to avoid the conversational spotlight, she wouldn’t take oui or non for an answer. Eventually, alcohol overcame her capacity to speak aloud. With her Francophile monologue internalised, her head rocked back and forth with Gallic dreaminess.

Later, we shifted to another bar where a guitarist sang gentle Bossa Nova songs to half a dozen quietly absorbed local couples. Two young Englishmen from our group shattered the peaceful mood with all the bumptious self-importance of Victorian missionaries. Pulling chairs up to a table in the middle of the room, they noisily announced the rules of the drinking game we needed to enjoy a beer. The other patrons looked on resentfully as the music faded beneath the rising foreign tide of voices, the clinking of bottles multiplying exponentially with the passing minutes. Feeling impotent within this obnoxious clash of cultures, I drank shamefully on till the game’s moronic conclusion. I blame myself for protesting too little.

After seven such nights, I fell ill. Given the near impossibility of sleeping to the rhythm of pounding drums, and the surfeit of beer, it was inevitable. Pelourinho was The Most Fun Place on Earth when I rolled up on a Tuesday night. Now that I was glutted on its ephemeral charms, the dream was slipping into sleepless nightmare. On my last night, my fragile health, rather than beer, caused me to vomit suddenly by the side of the road. With the instincts of a poaching striker, an opportunistic bystander burst into the periphery of my blurred vision – pawing at my unprotected pockets while harassing me for change. To his surprise, I stood up on steady feet with fury in my eyes. I clarified my position firmly. The Salvadorian experience was turning nasty on me – it was time to go.

~

Ten of us took a six-hour bus ride to the old mining town of Lençóis. Now that the diamonds were gone, this picturesque inland spot catered for tourists seeking the Great Outdoors. Among our crowd was a young dreadlocked German with a new girlfriend – a Brazilian whose wide smile was industrially strengthened by the thick railway braces straddling her teeth. His self-possession and relaxed demeanour ebbed away whenever she spoke to other men. Industry too must have been behind her spectacular and unlikely cleavage. The stereotypical physique of Brazilian women, Andrea had informed me, tended to couple shapely rears with petite breasts, but the growth of affordable plastic surgery and orthodontics in the country has now transformed many a goofy smile and modest embonpoint.

Also on board was a likeable Londoner called Tony. He first introduced me to Manu Chao – or at least his music. Tony was disturbed by the change in his old-school friend, Mo, who until a month ago was called Mohammed. Until Brazil, Mohammed had lived a life reasonably in keeping with that of his namesake. But now, Mo was embracing the previously foregone sins of the flesh. Alcohol was just the start, women usually the dessert. Tony hadn’t seen him kiss a girl before, but now Mo was racking up sexual conquests like a man possessed.

I first saw Mo when he swaggered into the hostel like a tough-talking sheriff barging through the swing doors of a saloon. Half a step behind was a striking Argentine. Lucia looked pale, beautiful, and uncomfortable in the glow of his youthful arrogance. Despite my friendly familiarity with Tony, or perhaps because of it, several days passed before Mo acknowledged me.

‘Tony seems to rate you,’ he muttered sourly as if fulfilling an unpleasant brief. It wasn’t much to work with so I said something similar back. To our mutual relief, it marked the beginning and end of our relationship.

Mo and Lucia brought a palpable tension to our trip along with their rucksacks. The cocky spring in Mo’s step was noticeably missing suggesting a sobering dose of rejection had stalled his rampaging – given further credence by Lucia’s unequivocal request for a single room at our lodgings. She was returning to the more restrained culture of Buenos Aires in a few days, and not a day too soon, she confided. Her brief journey across the border had confirmed many of the prejudices she brought with her – notably that Brazilians were given to gratuitous excess. ‘No class!’ she whispered to me conspiratorially.

For several days, I slept deeply, and relaxed in the wide-open spaces of this sparsely peopled haven. I quickly overcame my Salvador fever. We lounged in hot springs, dived beneath waterfalls and snorkelled in underground caves lit with eerie phosphorescence. I took a torch-lit tour through some giant caverns strewn with stalagmites and stalactites. Hundreds of metres beneath the surface, the cave extended for scores of kilometres in every direction. Whole armies of troglodytes could be lost and found in its myriad capillaries. Now healthy and refreshed, I made my way back to Salvador for the final leg of my journey. Ahead lay the iconic vistas of Rio de Janeiro.

Flight into the Unknown

The Brazilian hang-gliding club is found at the foot of a near vertical cliff. The precipice from which it operates rises sharply into the sky for half a kilometre. It is much quicker getting from the cliff to the club than from the club to the cliff. To reach the take-off strip, our car creaked and wheezed up its many corkscrew turns, sweating fumes and stress. The stress was mainly mine.

Miguel was a warm and reassuring presence, which helped as I would be tied to him when I plunged into the depths of the abyss. I’d planned to jump the day before, but fierce, screaming winds gave me another 24 hours to ruminate over my fear of heights. When strapped to an expert, there’s little to learn about hang-gliding, but I listened to the instructions intently with my back turned to the Great Drop. A wooden runway sloped down to the cliff edge like an abandoned road. Miguel stressed the importance of us both jumping off the cliff in smooth confident synchronicity.

We did a dry run. It wasn’t hard, but it didn’t end with a half kilometre drop. A few straps, like those you find on a rucksack, vaguely attached us. My rucksack often slips off. It seems I was to simply throw myself off the 500m cliff, limbs akimbo, and trust the harness to stop me plummeting to earth like a very scared stone. Miguel explained how we could be thrown off course if I touched the frame of the hang-glider that lay inches from my hands. I agreed that would be bad, while concentrating inwardly on the soaring and calming bars of a string concerto by the English composer Edward Elgar.

‘So, are you ready?’ he asked. The strings screeched somewhat.

‘Yeah, sure,’ I lied in falsetto staring blankly at my feet while the dreaded countdown started.

‘One…Two…Three…Go!’ The adrenalin marshalled my shaking legs forward within the mincing steps allowed by the straps. My feet were torn between the contradictions of movement and immobility as I looked up at a vast and endless sky. Lurching towards the blue, the ground dropped away from my feet. For a sickening split second… treading into nothing… I embodied the victim of my childhood nightmares falling out of control to an uncertain fate. But I didn’t wake up or hit the bottom.

The wind had caught us. Like some flimsy bug held within its mighty fickle fingers, we were cast off into airy space. As the crumbling cliff-face receded beneath my dangling and redundant feet, the potential nightmare took a dreamy diversion up and away from the threat of a fearful plunge. While I didn’t really doubt our craft’s airworthiness nor its pilot’s abilities, it was good to have them affirmed. The adrenalin still flowed, but the raging torrents required to hurl myself off a cliff gave way to the gentle waves of calm euphoria.

Miguel talked about his love life.

‘I have three girlfriends – that is good, no?’

With his power to cut me loose onto the jagged rocks, I completely agreed. ‘A good number,’ I said. ‘Enough for variety, but not too many to forget names.’

‘The latest is seventeen. You think that’s too young?

‘How old are you, Miguel?’ I parried, while confusing the packed beach below with an ant’s nest.

‘I am thirty-five. She is very beautiful with lots of… you know…’

As we sought the thermals, he flourished his apparently free hands expressively while grasping at the thin air for words to describe her nubile lines.

‘Curves?’ I ventured, settling down into the conversation.

‘Yes, curves!’ he shouted with satisfaction and a far-away look in his eyes. He took his hands off the frame again to celebrate the fact – much like a driver letting go of the steering wheel to discuss philosophy with a nervous passenger.

‘I love curves! Young curves!’

For the next ten minutes, we gently swept back and forth above the strip of land between mountain and sea. While the pedestrian dots in the streets drew no closer, it was the white flecks of the faraway waves that brought back a spasm of fear. Endless miles of dark rippled blue, bar the odd mast to be skewered on.

Our conversation drifted with the wind as we curled slowly downwards in wide sweeps above the villas of the rich. Our flying time reflected Miguel’s inclinations as much as the strength of the wind. Conditions of air and sea must be respected – those who defied the signs suffered the fate that levelled all mere mortals. But when the conditions were right – the Big Forces of Nature let you play awhile – so long as you didn’t forget your station.

My little adventure – pondered over neurotically for several days in advance – would be over in a few minutes. But Miguel would be back in an hour. Braced by my endorsement of younger partners, he could probably squeeze a romantic lunch into the break. His was an unusual office. Sometimes, presumably, he must be bored jumping off a cliff and flying an artificial wingover Rio de Janeiro.

He pointed to a landing spot on the beach in the lee of a smart hotel. The beach began to loom large with its stick figures now fleshing out to life-size humans, while I dimly remembered the importance of the landing process, the details of which I’d largely forgotten. Perhaps because I hadn’t really listened, preoccupied as I was with what would happen if I stopped on the edge of the cliff and Miguel ran off it.

‘Bend your knees!’ he yelled, as the sand grains rose one by one to greet us.

I bent my knees. In one gentle thump our four feet soaked up our collective weight. We were down. Miguel unhooked the hang-glider in one neat movement. A small crowd of Japanese tourists applauded us enthusiastically.

Like moonwalkers returned to earth, we strode up the beach with our kit slung nonchalantly over our shoulders. It was unclear which of us was the pilot. I smiled modestly and gave Miguel a congratulatory pat on the back.

The above extracts come from the journalist Gareth Mason’s recently published illustrated book Rum n’ Coca: Cautionary Tales from Latin America. Go to http://www.garethmason.com/synopsis for buying links, illustrations, excerpts, and other work.