University of Arizona anthropologist Jennifer Roth-Gordon spent 10 days in Brazil leading up to the 2016 Olympic Games with her children, two of whom are African-American and adopted.

During the visit, one shop owner yelled at her son, assuming he was a pivete (street kid). In another instance, a restaurant owner told the waiter not to let Roth-Gordon order any more food for the children, assuming they were begging.

In Brazil, racism is considered immoral and un-Brazilian and, in both instances, the business owners were excessively apologetic when they realized their mistake.

In her new book, “Race and the Brazilian Body: Blackness, Whiteness and Everyday Language in Rio de Janeiro,” Roth-Gordon explores what she calls the “comfortable racial contradiction” that exists in Brazil, a country that prides itself on its history of racial mixture and lack of overt racial conflict.

The book, published by the University of California Press, looks at how racial ideas about the superiority of whiteness and the inferiority of blackness continue to play out in the daily lives of Rio de Janeiro’s residents.

The book was 20 years in the making. Roth-Gordon, an associate professor in the University of Arizona School of Anthropology, went to Rio de Janeiro in graduate school and has gone back every year since.

Using linguistic and ethnographic analysis, she conducted interviews, recorded conversations and observed the day-to-day lives of people living in the housing projects and in the whiter middle- and upper-middle-class neighborhoods of Copacabana, Ipanema and Leblon. She hired a youth who lived in the housing projects as a research assistant.

Roth-Gordon said that one of the most interesting things about race relations in Brazil is that “there is profound racial inequality in Brazil and yet people do not think of themselves as racist.”

Brazilians have a history of promoting themselves as a racially mixed and racially democratic society. Many view their racial tolerance as one of the ways they are superior to other countries, especially the United States.

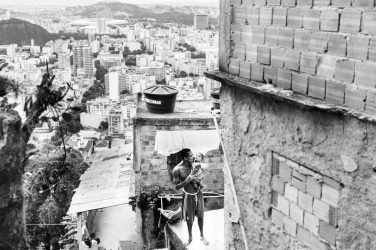

Roth-Gordon said that Brazilians certainly recognize the inequality that exists in their country, as the rich and poor live in close proximity.

All of those famous beaches connect by hills that have favelas, or informal settlements. However, many Brazilians believe that the inequality and prejudice is due to socioeconomic class rather than race.

For her research, Roth-Gordon wanted to dig deeper into day-to-day interactions to explore the discrepancy. “Racial inequality has be reconstructed every single day,” she said. “It has to be reproduced.”

In her book, Roth-Gordon emphasizes how Rio residents “read” others for racial signs. The amount of whiteness or blackness a body displays is determined not only through observations of phenotypical features — including skin color, hair texture and facial features — but also through attention to cultural and linguistic practices, including the use of nonstandard Portuguese and slang, which is associated with “poor, black shantytown living.”

Roth-Gordon made recordings of largely dark-skinned youth and played them for middle-class families. She cites an example of when a youth in the projects was talking about his fear of being robbed.

“I played the recording for a family, and they reacted as if he were the criminal,” Roth-Gordon said. “They ignored what he said. All they could hear, because to them slang is such a clear marker of criminality and poverty, was this is the language of a criminal.

“I have a whole chapter on how the white middle class raise their kids to make sure they are avoiding slang and speaking standard Portuguese. When you ask them why, they won’t tell you ‘I don’t want my kid to sound black.'”

The conversations Roth-Gordon collected include youth in the housing projects talking about their strategies for talking to the police, which include speaking standard Portuguese.

“We don’t just size people up by what they look like, especially in a place like Brazil where people are racially mixed,” Roth-Gordon said. “How should this cop treat this kid? Like a poor black criminal or like a middle-class citizen?”

Roth-Gordon believes that acknowledging or studying only overt acts of racism is like studying the “tip of the iceberg.”

“It’s clearly so much deeper than that,” she said. “What is under the water is creating a base for what we can see.”

For example, with regard to police killing black men, she says many are prepared to punish those instances. “But they are unwilling to go beyond that and say these cops are reacting to these ideas that we have about blackness, linking it to criminality.

“And these ideas are not just ideas. We have a system in both the U.S. and Brazil that disproportionately locks up people of color, a system of justice that has never treated black men fairly. Those ideas are the rest of the iceberg.”

Jennifer Roth-Gordon will speak about her book “Race and the Brazilian Body: Blackness, Whiteness and Everyday Language in Rio de Janeiro” during the Tucson Festival of Books, to be held March 11 and 12, 2017.

Roth-Gordon will be part of the panel “A Conversation on Segregated Spaces” at 10 a.m. March 11 at the UA College of Social and Behavioral Sciences pavilion.

With scholars Reginald Dwayne Betts, Jeff Chang and Tyina Steptoe, Roth-Gordon will explore the ways in which racially segregated spaces are constructed through language, law and culture in the U.S. and beyond.

Lori Harwood – University of Arizona College of Social and Behavioral Sciences