Alongside the Brazilian Amazon’s vast soy and cattle ranching economy – a major driver of deforestation – sits an older, more sustainable system of families and cooperatives producing forest products including the palm fruit açaí, rubber and pharmaceutical ingredients.

That “bioeconomy”, with its legions of small producers, including Indigenous communities, receives just a fraction of the flood of investment pouring into expanding soy and cattle.

As Brazil tries to protect its fast-vanishing rainforest, reduce inequality and build a more sustainable economy, finding ways to shift investment toward expanding the bioeconomy may be the best chance to protect the Amazon and its people, experts say.

“We have a model that looks at our natural resources from an exploitation point of view,” said Carina Pimenta, a founder of Conexsus, a Brazilian non-profit that helps traditional producers get the business expertise and investment they need to grow.

By instead proactively developing and strengthening the bioeconomy, Brazil can not only protect its forests and meet its climate change and biodiversity commitments but boost its economy and channel cash to communities with a stake in keeping nature intact, she said.

“The economic benefits are larger in this sustainable system” – not least because continuing Amazon destruction will disrupt the rainfall Brazil’s cattle and soy economy depends on, said Pimenta, who was recently named National Secretary for the Bioeconomy in President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s environment ministry.

“The problem is we have not promoted it as a development path. People are used to another means of production – and this is a cultural change that needs to be induced by public policy.”

Chocolate to açaí

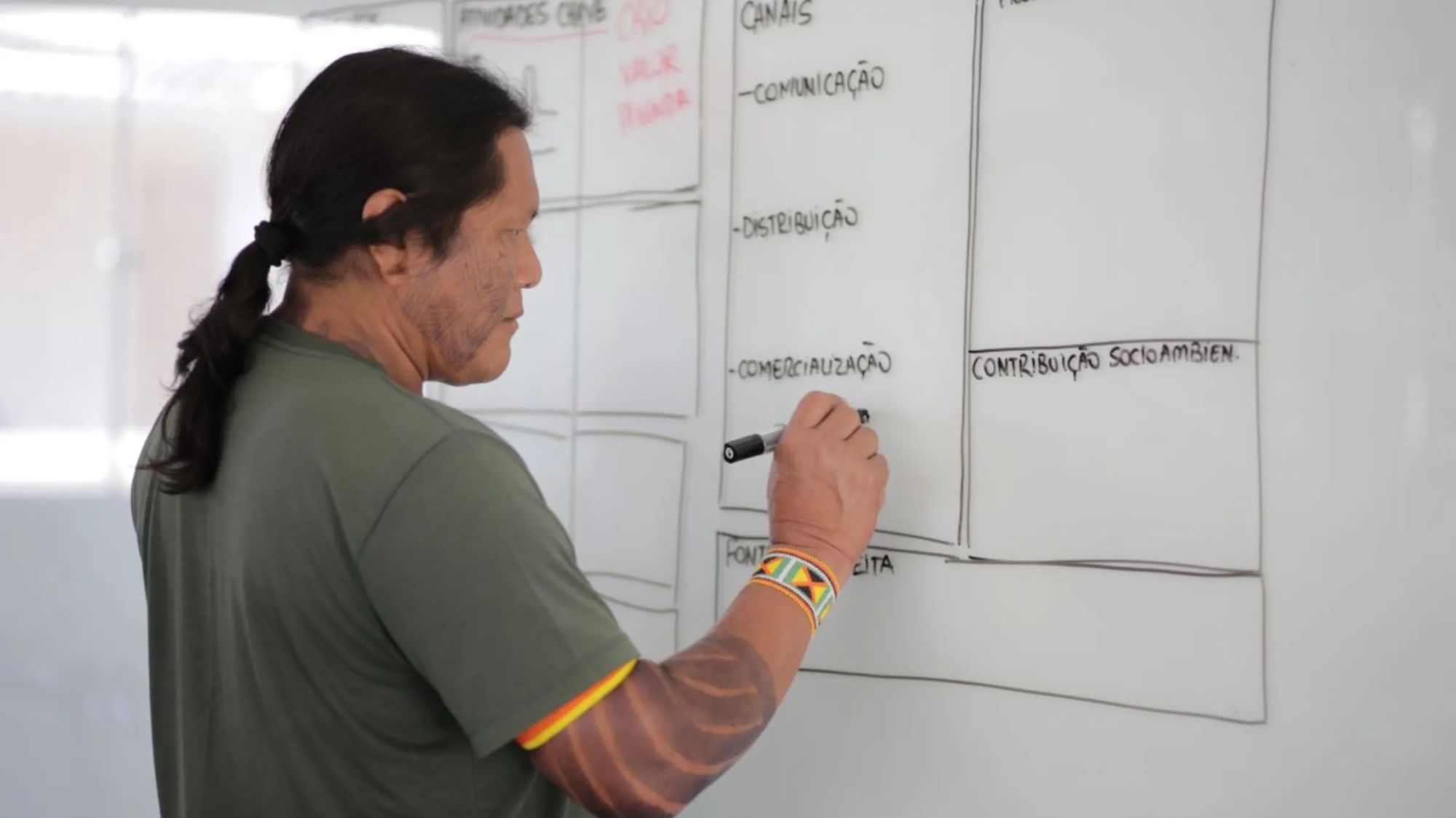

Conexsus, which won a US$ 2.25 million prize for social innovation this month from the U.S.-based anti-poverty Skoll Foundation, works on the ground with small producers of products such as açaí and chocolate, improving practices, adding skills, and helping line up finance.

The aim is to turn small cooperatives and subsistence-level production into thriving, sustainable businesses.

In the Amazonian state of Pará, for instance, Conexsus has helped Coopatrans – a cooperative of cocoa farmers that produces their own brand of chocolate, Cacauway – with technical assistance on how to produce better quality cocoa beans.

Cooperative members also have access to mentoring on how to more effectively run their growing business, and have received a line of low-interest credit which has helped them pay farmers on time, improving relationships.

“Before, it took us 30 to 60 days to pay them, or sometimes even longer than that,” said Hélia Félix, a member of the collective. “Now our associates know that if they deliver their produce, they’ll be paid upon delivery.”

With help from Conexsus, “we now see (Coopatrans) as a business” rather than just a collective, she said.

In Marajó, a region of Pará, Conexsus has similarly helped açaí producers cut waste, get access to credit, process açaí into higher value products and sign supply contracts, including with schools.

“They are on this path. The potential is to accelerate this path and offer the tools, the solutions and investments for this to happen faster,” Pimenta said.

Rising deforestation

Conexsus got its start in 2018, as Pimenta and other sustainable development experts, many of them Amazon specialists, watched in dismay as the country’s Amazon deforestation rate rose, largely as soy and cattle ranching expanded.

They formed a collective, aiming to use their experience to try to reverse the trend and drive investment to more sustainable economic activity, said Marco van der Ree, interim executive director of Conexsus and a member of the original 40-member expert group.

Intact Amazon forest has an economic value four times higher than the same land turned into cattle pasture, if benefits such as the forest’s contribution to producing rainfall, clean air and a stable climate are considered, according to work by Carlos Nobre, a leading Brazilian scientist and climate change expert.

But “the financial system doesn’t look at things in that way,” van der Ree noted – which is one reason most finance continues to go to cattle and soy expansion.

Today just 22% of subsidized rural credit channeled through Brazil’s public banks goes to support bioeconomy businesses, Pimenta said – something she hopes to change.

Even more important is persuading Brazil’s private banks that the bioeconomy is a good investment – a change that can be encouraged with new government incentives and policy, and through philanthropic investments that prove the case, van der Ree said.

“It’s hard work, to get change done,” he said. But as private banks begin to see returns, the hope is that funding for the bioeconomy could become self-sustaining.

Broader aims

While about half of Conexsus’ work focuses on the Amazon, the organization – with its team of on-the-ground advisors – also targets other key Brazilian ecosystems, from the Cerrado, a highly endangered tropical savanna, to the coastal Mata Atlântica rainforest.

“There are amazing biodiversity products in all those biomes,” van der Ree noted.

Efforts to build a Brazilian bioeconomy could also happen on about 50 million hectares of degraded land in the country that has the potential for restoration, Pimenta said.

But whether selling carbon offset credits from protected forest will become a big part of a more sustainable Brazilian forest economy remains unclear, she said.

Carbon credits could play an important role in paying for land restoration – but issuing credits for protecting existing forest is more complicated, with carbon markets unregulated, land ownership often unclear and “carbon cowboys” moving in to profit, she said.

“This is spreading across Brazil. Communities are not well prepared and equipped. That’s why regulation is important to protect their rights,” Pimenta said.

Building sustainable nature-based businesses in the Amazon is a surer bet, she said, particularly because “they generate wealth that stays in the region,” unlike large-scale soy and cattle production and many carbon credits.

The shift to a new economy “is not going to happen very quickly because the complexity of this is high,” Pimenta noted. But “we have the right path for it to happen. We are in the right moment, with the right people to do this.”

Laurie Goering is Climate Change Editor for the Thomson Reuters Foundation based in London. Previously she was a Chicago Tribune correspondent based in New Delhi, Johannesburg, Mexico City, Havana, Rio de Janeiro and London.

Fabio Teixeira is a Climate Correspondent for the Thomson Reuters Foundation based in Brazil, covering climate change and labor issues. Fabio has worked for national newspaper O Globo and has a post-graduate degree in Investigative Journalism from the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism.

This article was produced by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Visit them at https://www.context.news/