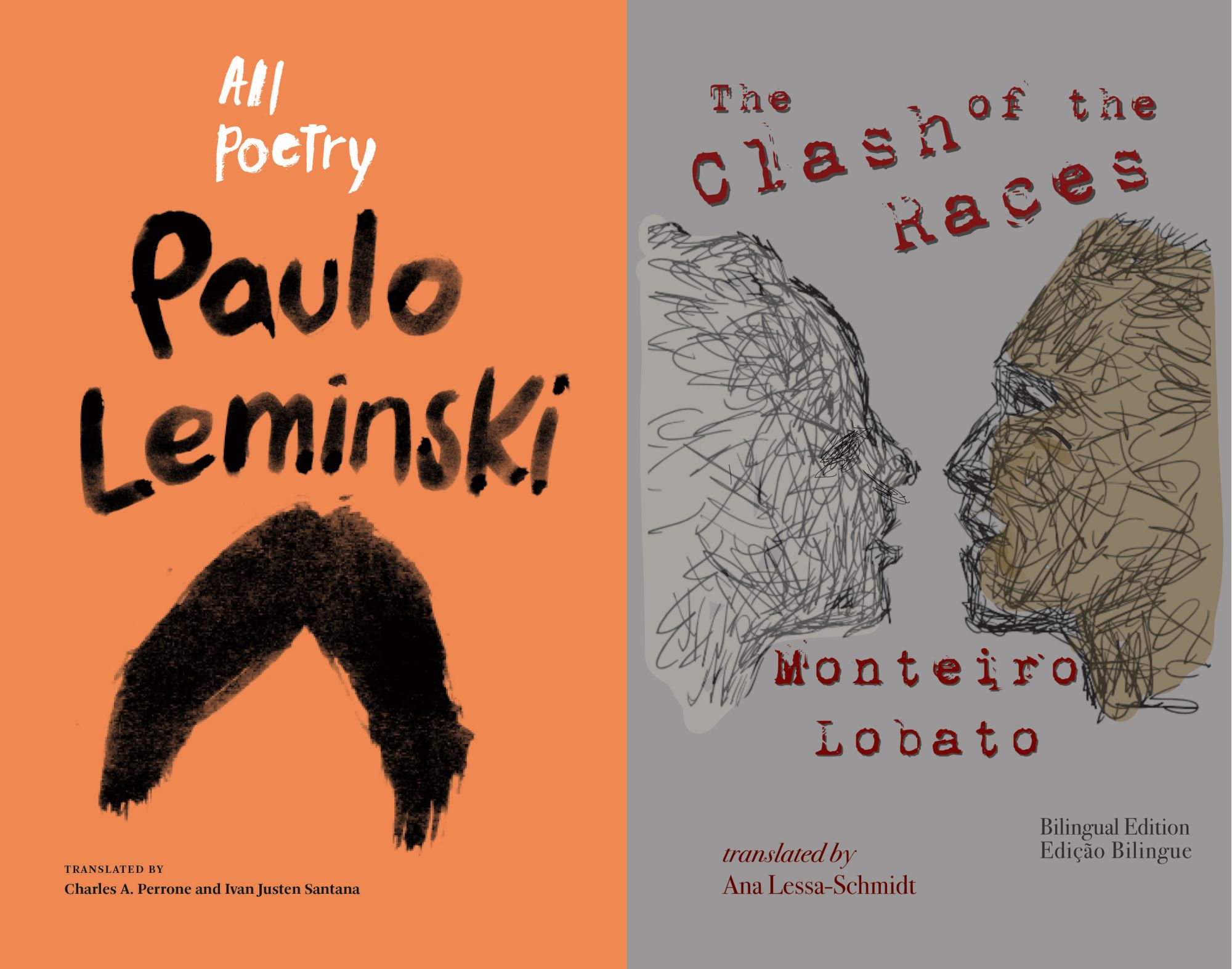

New London Librarium, a premier publisher of translations of Brazilian classics, has just released two books that introduce two writers, Monteiro Lobato and Paulo Leminski, who are famous in Brazil yet still little known in the Anglophone world.

Paulo Leminski’s All Poetry (Toda Poesia), translated by an American, Charles A. Perrone, and a Brazilian, Ivan Justen Santana, is a most impressive accomplishment. Leminski’s unique use of language, often breaking words into graphic images, often rhyming, often playing with puns and slang in Portuguese, would seem impossible to render into another language.

But with twists of the English language (and often a bit of a stretch), the binational duo has managed to pull off the impossible.

For example:

o p que

no pequeno &

se esconde

eu sei por q

só não sei

onde nem e

gets rendered as:

the p that’s

in the poky &

hides itself

i know y

i just don’t know

where neither and

The 348-page volume is the first and only translation of all poetry attributed to Leminski, which was originally published as Toda Poesia.

Leminski (1944-1989) was one of Brazil’s most popular poets. Toda Poesia sold in excess of 200,000 copies, a number reached by few poets in any country.

Leminski was born in Curitiba, Paraná. Once intending to be a monk, he studied Latin, theology, philosophy, and classic literature. After abandoning his pursuit of a religious life, he became an ardent Trotskyist and avant-garde writer and poet. His literary works included translations, journalism, advertising copy, song lyrics, literary criticism, and biographies.

Some of Leminski’s songs were sung by such greats as Caetano Veloso, Ney Matogrosso, Zizi Possi, and Gilberto Gil, among many others.

The Black President

New London Librarium has also just published a translation of a startling novel by Monteiro Lobato, O Presidente Negro ou O Choque das Raças, under the title The Clash of the Races.

Translator Ana Lessa-Schmidt, who has also translated works by Machado de Assis, Mário de Andrade, and João do Rio, was courageous to take on this novel. On the one hand, the plot reaches into the future with astonishing accuracy. On the other hand, however, it harks back to Lobato’s time with what today would be considered off-putting, if not quite malicious, racism.

Like many New London Librarium translation, Clash is bilingual, with the English and the original side by side on page spreads.

Lobato is most known for his children’s books, many of which feature the famous Yellow Woodpecker Farm (Sítio do Pica-Pau Amarelo). Clash, however, delves into some of the most serious of adult socio-political concerns.

The plot posits a scientist who has invented a machine, a “porviroscope,” that can look into the future. While a nascent love affair occupies key characters in the 1920s, the porviroscope watches an election in the United States in 2228.

The prescience in the plot is uncanny. In a three-way election, a conservative white male candidate runs against a white feminist and a Black male. The nation is on edge with imminent racial violence. Unable to retain their power through elections, whites revolt in a violent effort that resembles the Nazi’s “final solution” of the 1940s.

Lobato also conjures up technologies that were still half a century or more in the future — cell phones, email, television, the internet, instant election results, and the one we are still waiting for, the object transporter imagined in Star Trek films.

There are many angles to consider in this convoluted plot and its underlying stereotypes of Blacks. In an Introduction well worth reading, Vanete Santana-Dezmann offers insights into the book, the author, and the nature of dystopian fiction.

Readers will have to decide whether the racism in Clash was worth reproducing in translation. The stale prejudices of the 1920s are unlikely to inspire racist values today. Rather, they should remind readers of the stereotypes of a century past, prejudices worth remembering without emulating. The novel is worth reading for its many intriguing insights into the nature of men, women, society, science, and democracy.