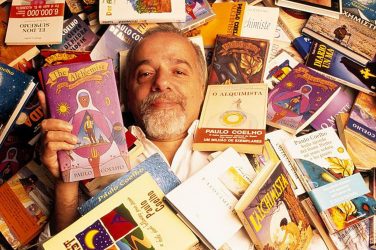

Paulo Coelho’s latest book to be released in the US is neither a memorable tale nor is it particularly well written. While

The Alchemist was an auspicious beginning for the author, if he doesn’t change his tune he may soon lose his American audience.

By the River Piedra I Sat Down and Wept, by Paulo Coelho, trans. by Alan R. Clarke (Harper San Francisco,

240 pp., $20)

“True love is an act of total surrender… This book is about the importance of that surrender.”

Paulo Coelho has taken a new approach with a familiar subject. His fourth novel to appear in English is narrated

by a young woman of twenty-nine named Pilar, whose childhood friend — an unnamed `he’ — is now a reputed

miracle-worker. They have not seen each other in over a decade but have sporadically remained in touch.

Pilar has been going to school in Zaragoza, Spain, and one day she travels four hours by train to Madrid to hear

him lecture. She listens from the audience as he begins: “You have to take risks. We can fully understand the miracle

of life only if we allow the unexpected to happen.”

She waits for him afterwards. “I believe in the feminine side of God,” he tells her; and later he’ll say that “One of

the faces of God is the face of a woman.” Not only is he paying obeisance to the feminine principle in all things —

God is the father, and the mother — he also claims to have seen the Goddess. It was She who bestowed upon him the

powers of healing.

Pilar accompanies the old friend with whom she’s been reunited to Bilbao, where he is to lecture. He reveals to her

that he has loved her consistently these many years, but in this matter Pilar doubts his sincerity. He tells her: “I’m

going to fight for your love. There are some things in life that are worth fighting to the end for… You are worth it.”

If the reader has leafed through any two of Coelho’s three previous books —

The Alchemist, The Pilgrimage, The Valkyries

— then it will be noticed that the same themes are again being explored by characters who tend to

be mouthpieces for the author: “The universe always helps us fight for our dreams, no matter how foolish they may

be. Because they’re our dreams, and only we know the effort required to keep them alive.” Or, “The moment we

begin to seek love, love begins to seek us. And to save us.” Variations of these lines can be found in all of Coelho’s novels.

Pilar, it turns out, is having difficulty in `letting go.’ Part of her is still back in Zaragoza studying for final exams

and relaxing with her friends; the other part really would like to surrender to the passions of the moment. This may be

why Coelho has cast his tale in what is simultaneously an interior monologue and a journal (written after the fact) that

cover the events, day by day, of one fateful week in December, 1993. Since the main thrust of the story is also about

ousting the Other, or presiding over that part of oneself that says we should be cautious, seek money and comfort, the

author could have generated some real inner tension, resulting in believable character growth, but Pilar is not only

childish (headstrong one minute, indecisive the next) as well as a bundle of conflicting emotions, she later spouts the kind

of wisdom that even Socrates would be hard-pressed to top.

Perhaps because of his unexpected proximity to her, our unnamed miracle-worker suddenly seems to be

buffeted about by the winds of uncertainty. When Pilar capitulates to her innermost thoughts and dreams, to paraphrase

another of Coelho’s themes, and then admits that she, too, is in love, he has to decide how to sever and yet retain his ties

to the ways of his church. He seeks to embrace and adapt, and we are led to believe that he resolves his dilemma,

that he has been able to reconcile his proselytizing the faith with his being married to Pilar.

Ultimately, then, this book is a pilgrimage for all concerned, and not just an inner pilgrimage either since the last

few days take place in Saint-Savin, just over the Spanish border into France, and in Lourdes, where in 1858 the Virgin

Mary appeared several times to a poor girl named Bernadette.

One can read By the River Piedra I Sat Down and

Wept as a love story with spiritual overtones, but it is not

a particularly memorable tale nor is it particularly well written. In this regard, it joins

The Valkyries as a book with little to recommend it: both books seem awkward and simplistic. While

The Alchemist was an auspicious beginning

for Paulo Coelho in this country, if he doesn’t change his tune (or at least his presentation of it) I’m afraid that he

may lose his audience. Should that happen, I just don’t think he’ll get it back.

An excerpt:

“The gods throw the dice, and they don’t ask if we want to be in the game or not. They don’t care whether you

leave behind a lover, a home, a career, or a dream. The gods don’t care whether you have it all, if it seems like your

every desire can be met through hard work and persistence. The gods don’t want to know about your plans and your

hopes. Somewhere in the universe, they’re throwing the dice — and you are chosen. From then on, winning or losing is

only a matter of chance.

The gods throw the dice, and free love from its cage. Love is a force that can create or destroy — depending on

the direction of the wind at the time it was set free.

For the moment, the wind was blowing in his favor. But the wind is as capricious as the gods — and, deep inside

myself, I began to feel some gusts.