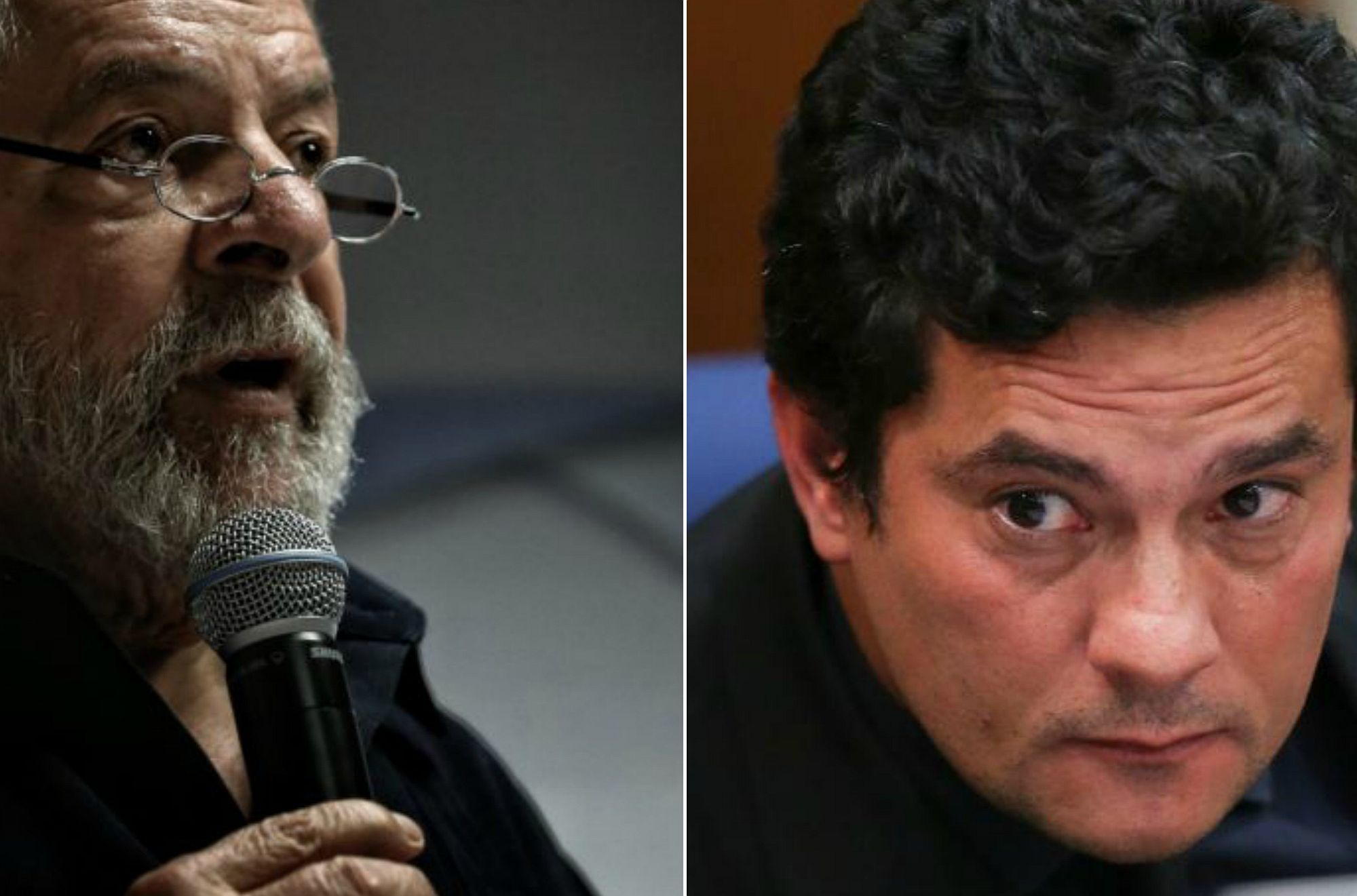

On Thursday, April 5, Judge Sérgio Moro of Curitiba issued a curt prison invitation to former President Lula in the latest chapter of Lava Jato, the biggest corruption scandal in Brazil’s history. Judge Moro gave Lula, co-founder of the Workers’ Party (PT), until 5 pm the following day to arrive in Curitiba to be jailed in a specially designed room.

Lawyers advised Lula to accept Moro’s invitation, but PT’s party leaders objected, preferring to force the lawyers to continue filing additional last-minute appeals to postpone Lula’s 12-year prison sentence.

Lula, age 72, received a string of visitors at his office at the Lula Institute in São Paulo on Thursday, including former President Dilma Rousseff. Moro’s deadline came and went with Lula spending Friday surrounded by his sons, friends, and party leaders at the Metalworkers Union in São Bernardo do Campo, a suburb of São Paulo. This is the Union that provided Lula with his first national stage.

In a close vote by the Supreme Court late Wednesday night, 6-5, which took nearly eleven hours to complete, Lula, Brazil’s first working-class president, lost his last hope to escape prison.

Unlike in the US, Supreme Court decisions here are televised live, and each Supreme Court justice is permitted to speak for as long as s/he wishes detailing the rationalizations behind their vote. At the conclusion of the monologue, the justice casts a vote, but until then nobody knows with certainty which side the justice will take.

Court observers predicted a close vote as the eleven judges wrestled with the implications of sending a former president to prison. Justice Gilmar Mendes, traditionally a critic of Lula, voted in favor of him. “If a court bows, it might as well not exist,” said Mendes.

Past midnight on Wednesday with the vote tied 5-5, Chief Justice Cármen Lúcia cast the deciding vote. She knew if she allowed Lula’s request for habeas corpus and let him free after his conviction on corruption charges, it would open the prison door to other indictments stemming from Lava Jato.

The president of the Workers’ Party, Senator Gleisi Hoffmann of Paraná, told journalists that Lula should not give Judge Moro the satisfaction of having Lula voluntarily come to Curitiba on Friday to be arrested. “Lula remains our candidate, first of all because he is innocent,” Hoffmann said. “If he is jailed, we will consider him a political prisoner and we will be by his side.”

Under the so-called Clean Slate Law (Lei da Ficha Limpa), a convicted criminal may not serve in public office. Should Lula’s candidacy for president be rejected by the Superior Electoral Court (TSE), PT does not have a candidate with Lula’s popularity to replace him.

In fact, there isn’t another candidate from any party who has Lula’s popularity. When Lula finished his second term as president in 2010, he left office with an 87 percent approval rating, which is unprecedented for any president in any country. At the time, US President Barack Obama called him “the most popular politician on Earth.”

Lula today maintains a loyal following, particularly among the working class and the Unions, and for good reason. First, PT played a key role in easing out the military regime and opening the door for democratic rule in the 1980s. As the head of the Metalworkers Union, Lula organized several critical strikes against the military dictatorship.

Second, PT, launched in 1980, influenced the government, as the opposition party, in its writing of a new Constitution, which was signed in 1988. In the Constitution are numerous laws protecting workers, both blue- and white-collar. For example, the Constitution guarantees women paid maternity leave and all workers receive at least 30 days paid vacation annually.

Third, during Lula’s two terms as president with his PT as the ruling party, many laws benefiting the poor and working class were passed. Some of the laws were so extensive, such as Bolsa Família, that they will have a lasting positive effect in Brazil for generations.

Bolsa Família is a social welfare program providing small cash awards to mothers who must verify that their children are attending school and being vaccinated. PT didn’t invent Bolsa Família; it was started by former President Henrique Cardoso.

Nevertheless, PT greatly expanded its size and tied payments to the health and welfare of children. Also, the disbursements were restricted to only women, as their husbands were found to be less financially reliable.

This system of direct social welfare has been so successful that it has become an international model for the eradication of poverty. For the first time in its history, the government, led by PT, found a way to ensure that the majority of Brazil’s children are in school and vaccinated.

In addition to bolstering the working class and ensuring vaccinated children, during the 13 years that PT was the ruling party, it passed a series of anti-corruption laws, such as Ficha Limpa, which are altering the history of impunity for Brazil’s richest and most powerful men.

Besides Ficha Limpa, federal prosecutors like Sérgio Moro and his team in Curitiba were given greater leverage in using plea bargains (Delação Premiada). (The extensive use of plea bargains has been a standard practice for prosecutors in the US for fifty years.)

It is only by utilizing plea bargains that the Lava Jato corruption investigation has been able to convict 120 powerful politicians and businessmen, such as billionaire Marcelo Odebrecht, the CEO of his family’s company, the largest construction company in Latin America.

Today, many of these powerful men remain in prison, including Eduardo Cunha, the former Speaker of the House, who was one of the most influential politicians in Brazil at the time of his arrest. The scandal has also resulted in the government collecting billions of dollars in restitution payments from Odebrecht and other construction companies like OAS.

In the fight against corruption and oligarchy, Sérgio Moro is hailed as a hero, and his efforts have become a rallying point for anti-corruption movements throughout Latin America.

In a final blow to the wealthy and powerful, another law was passed during the PT administration that puts all people into prison after they’ve suffered a court conviction and then lost their first appeal. In the past, anyone convicted of a crime would remain free until all their appeals had been exhausted, which could take decades.

In a sad irony not lost on Lula’s supporters, Moro is able now to incarcerate Lula because of a change in the appeals law championed by Lula himself, when he fulfilled a pledge to clean up political corruption during his four campaigns for the presidency.

Thanks to a libertarian approach by Brazilians to the laws of the land, there is an abundance of lawsuits clogging the court system. There are more lawyers per capita in Brazil than in the US. The abundance of lawsuits, combined with an appeals process that allows for multiple appeals of the same case with the lack of legal precedence, creates an ineffectual judicial system.

Now, anyone convicted and losing a first appeal has to conduct any further appeals from prison. In the past, the upper class who could afford to hire powerful legal representation have been able to avoid prison because after their case reaches its final appeal, a decade or two later, the statute of limitations has run out and the case is dismissed.

The statute of limitations in Brazil includes all subsequent appeals. In the US, the statute of limitation applies only to when the initial case comes to trial. Any appeals to a conviction are not included in the deadline limitation.

Thanks to these critical changes in the legal system that occurred during the PT administration, which gave far greater power to the judiciary, Brazil’s oligarchs, once addressed as Coronéis, are now becoming an anachronism.

They have ruled Brazil like a personal fiefdom since the country’s independence from monarchy. For two centuries, Brazil, like other developing countries, has been forced to live under the chains of a socioeconomic system that was not all that different from monarchy. Remarkably, in just 13 years in power, PT found a way to break those chains.

In addition to the end of impunity for the wealthy and expanding workers’ rights and children’s healthcare, during Lula’s presidency Brazil experienced its longest period of economic growth in three decades, allowing his administration to spend lavishly on social programs. Tens of millions were lifted out of poverty.

Not only have the poor and working class benefited financially thanks to Lula, but the country’s commitment to democracy has been solidified with a stronger judiciary to challenge the impunity of the wealthy.

Today, what is tearing Brazil asunder is the agony of watching a political hero go to jail. Lula was convicted last July of accepting US$ 1.2 million in bribes from contractor OAS in the Lava Jato investigation. (Although Lula served two consecutive terms as president, he is permitted to run again after taking a term off.)

Lula was given a sentence of 9 ½ years by Judge Sérgio Moro stemming from plea bargain testimonies. On appeal, the court review upped Lula’s sentence to 12 years.

While the official line from PT, as noted by Gleisi Hoffman, is that Lula is a political prisoner who is guilty of nothing, most people in Brazil aren’t buying this line. The general consensus is that Lula is guilty of corruption, but if the majority of the people wish to vote for him they should be allowed.

In Brazil there is a famous expression regarding politicians: “He may be corrupt, but he gets things done.” Political corruption has been so endemic throughout the country’s history that it’s easy to overlook.

The country’s Unions, which represent all workers other than the self-employed – from bus drivers to teachers to bank employees to factory workers – are in strong support of PT. Frequently they appear in protest marches in support of Lula wearing red, brought together by CUT, a national federation that organizes the country’s Unions.

What is the most painful element in all this for PT and its supporters is the knowledge that Lula would never be facing a prison term if it weren’t for the anti-corruption laws that PT itself championed, giving more power to the weak judiciary – namely, Ficha Limpa, Delação Premiada, and mandatory imprisonment following the first lost appeal.

In fact, it was this final law change that erupted on Wednesday, April 4, when the Supreme Court ruled on Lula’s lawyers writ of habeas corpus. The Court was asked to decide whether Lula should be allowed to remain free while he continues his appeals process, having lost his first appeal.

Although Lula lost his first appeal in the regional federal court in Porto Alegre, he has one or two more possible avenues of appeal of his 12-year sentence. However, critics of PT point out that even if Lula should win his case on appeal and have his conviction overturned, there are at least six other indictments pending against him in Curitiba and Brasília on similar corruption charges linked to the Lava Jato case.

Brazil is now witnessing the imprisonment of a former president, the first time in the country’s history. It’s worth noting that this has happened in other countries and not only developing countries.

The former president of South Korea is currently in prison, as she was sentenced last week to 24 years on corruption charges, illustrating ties between a country’s political elite and its largest corporations.

“Wednesday was D-Day in the fight against corruption,” tweeted Deltan Dallagnol last week, a lead prosecutor in Lava Jato, referring to the Supreme Court decision. He was worried that a decision in favor of Lula would send a message of impunity to other Latin American countries.

Also last Wednesday, General Eduardo Villas Boas, the commander of the Brazilian army, tweeted that the military “repudiates impunity” and said the army was “attentive to its institutional missions.” His comments were seen as an effort to influence the Supreme Court to rule against Lula.

The details of the Lava Jato scandal have been headline news for years in Brazil and are so ingrained in the Brazilian psyche that Netflix this month launched a series based on the details of the arrests of the Lava Jato participants, told from the perspective of the Federal Police. It’s called “O Mecanismo” and was made in Portuguese by Brazilian director José Padilha with a Brazilian cast, subtitled in English.

Corruption allegations against PT began before Lava Jato in a case known as Mensalão, which went to the Supreme Court at the end of Lula’s first term and saw jail sentences handed out to several high-ranking PT members, including Lula’s right-hand man, José Dirceu, his Chief of Staff, who probably would have been Lula’s handpicked successor and Brazil’s president instead of Dilma Rousseff had Dirceu not gone to prison.

While Lula supporters may be invigorated by his imprisonment, many others have been equally vocal in support of Judge Moro and his anti-corruption efforts. Thousands marched on Wednesday in several cities including Rio, São Paulo, and Curitiba in favor of seeing Lula in prison.

With Lava Jato indictments continuing in the courts, combined with the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, who had never held public office before being elected president, PT supporters see Lula’s prison term and Dilma’s impeachment as an affront to democracy.

Supporters believe Lula is being imprisoned solely because he’s the front-runner in polls for this year’s election, and similarly view Dilma’s removal from office as a “political coup.”

They think the public prosecutors are waging a personal war against PT. Lula has stated publicly he would not have been convicted were it not for the prejudice of the media, in particular Globo news.

What’s even more troubling than the irony of an extraordinarily popular president going to jail because of laws that he himself pushed through congress, is the political and economic instability Lula’s incarceration is creating. Political instability always has a negative effect on the economy, something Brazil can hardly afford at this juncture.

Following the impeachment of Dilma in 2016, the country has been led by Dilma’s Vice President, Michel Temer, who is not in PT. Temer, like many of his colleagues in congress, is not considered a clean politician, and his approval ratings are in the single digits.

Nevertheless, despite Temer’s lack of popular appeal or electoral mandate, Brazil’s economy has been successfully struggling back this year from a two-year recession that began with PT. While unemployment remains very high, about 12 percent, the inflation rate has fallen below the government’s predictions, down to developed-country levels, and the country’s economy is officially growing again.

Brazil’s Selic, the federally mandated interest rate, has fallen from a high of 14 percent to 6.5 percent today, adding fuel to the fire of the anti-PT forces. As the American saying goes: “People vote with their pocketbooks.” A strong economy is the only hope for financing desperately needed social programs.

Meanwhile in a nutshell, the current political situation here is chaotic and dangerously unstable. The polarization between PT supporters and critics is extraordinary and unyielding. When Lula finally arrived in Curitiba late Saturday night to begin his incarceration, he was greeted on one side by people weeping and on the other side by people celebrating with fireworks.

Not surprisingly, some Brazilians have become confused in this political dichotomy. For example, retired employees from state-owned companies like Caixa Bank and Petrobras are facing devastating losses of their retirement funds.

These retirees have been forced to give back a percentage of their monthly pension checks to offset the losses that occurred from bad investments made by their pension funds. These losses occurred during the PT regime and are linked to Lava Jato.

Thus, Union members who could always count on the support of PT are now confronting an economic corruption fallout caused by PT, as the pension fund losses are taken directly out of the retirees’ pension checks.

For those who are fortunate enough to be gainfully employed, an equally troubling crisis is arising for this year’s presidential election. A fundamental question of political philosophy has presented itself: In a true democracy, shouldn’t the populace be permitted to elect whom they choose even if he’s a convicted criminal?

A statement issued by PT on Thursday said, “The Brazilian people have the right to vote for Lula, the candidate of hope.” As a result of his popular support, it would not be surprising to see Lula freed from incarceration this year, and it is also possible to imagine a scenario where his name is on the ballot in October, even if he’s still in prison.

However, it seems extremely unlikely that the courts will allow him to serve another term as president even if he were elected because of the Ficha Limpa rule. While PT affirmed again on Monday, April 9, that Lula would be their candidate in October, they also possibly signaled their doubts by announcing on the same day they would be moving their headquarters from São Paulo to Curitiba.

PT does not have another candidate who could easily win an election should Lula’s name not appear on the ballot. As most politicians outside PT are betting on this scenario, a huge vacuum has opened up, allowing for at least a dozen candidates to express their interest in running for president this year.

In Brazil voting is mandatory, but it’s legal to vote for no one, a null vote (nulo). With so many candidates vying for attention and PT supporters threatening millions of nulo votes, the field is wide open.

Additionally, it remains to be seen how much power Lula, as a prison martyr, will have in influencing his party’s direction and the upcoming election. Will he convince PT to nominate another candidate?

The two largest parties will certainly back traditional candidates like Geraldo Alckmin (PSDB), the governor of São Paulo state. Aécio Neves, who ran previously, is interested as is the current president, Michel Temer, although they both have been linked to Lava Jato.

The Finance Minister, Henrique Meirelles, who wants to take credit for bringing the country out of the recession, has resigned from his position in the Temer administration in an apparent move toward running. Brazilian financial markets rallied after the Supreme Court vote, which investors believe increases the chances of a market-friendly candidate like Temer or Meirelles winning in October.

Meanwhile, the left has a slate of candidates ready including Marina Silva, who has run twice before for president, coming in third in the last election. She was formerly a Minister with PT, then resigned and later ran for president as the Green Party candidate, and now has founded her own party (Rede).

Silva was a colleague of the assassinated environmental hero Chico Mendes. Another strong candidate on the left is Ciro Gomes (PDT). Fernando Haddad (PT), the former mayor of São Paulo, is a possible replacement on the ballot for Lula.

In addition, there are rumors that Joaquim Barbosa, the retired Chief of the Supreme Court, who was appointed by PT to the Court but instead put PT politicos in prison during the Mensalão trial, may be running. Last week he announced he was leaving PT and joined the Socialist Party (PSB).

In Curitiba, October voters may capitalize on the anti-PT, anti-corruption fervor to push out Senator Gleisi Hoffman, who is the head of PT and under investigation for corruption along with her husband.

Alvaro Dias, a senator from Paraná who is not up for re-election this year, is viewed by some as an example of a new wave of young, honest politicians. He has been encouraged to run for president but has shown no signs of moving in that direction.

“It’s going to be a very tumultuous election. The left has lost its reference,” said Carlos Melo, a professor of political science at the Insper Institute of Education and Research in São Paulo. He added, “The party doesn’t have many options because Lula was so central and important. But you can’t keep insisting on Lula forever. Someone will have to take over this role.”

Should the Superior Electoral Court vote to keep Lula’s name off the ballot, the candidate who is currently in second place in the polls behind Lula is an ex-military congressman, Jair Bolsonaro (PSL). His support comes from the military and social conservatives who applaud his law-and-order agenda of greater police power and making guns easy to obtain for the average citizen.

Bolsonaro celebrated the Supreme Court’s decision against Lula. “Brazil scored a goal against impunity, against corruption, but it is just a goal,” he said in a video. “The enemy has yet to be eliminated.” His respect for the two decades of military dictatorship in Brazil is well known.

However, Bolsonaro has his own problems with the courts, being fined two years ago for insulting a female congresswoman. That, along with his opposition to progressive issues such as legalizing abortion and gay marriage, have made him an easy target for liberals and leftists. Brazil’s LGBT community has labeled Bolsonaro a cleverly disguised fascist.

Experts say Lula’s chances of making it onto the ballot are not good, but some think that could work in his party’s favor. “They have the victim card on their side, they’re going to play that,” said Monica de Bolle, a Brazil expert at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

“They won’t jail my thoughts, they won’t jail my dreams,” Lula told a crowd of 5,000 people in Rio de Janeiro on Monday before his arrest. In a survey conducted by DataFolha Institute back in January, 53 percent of Brazilians felt that the former president should be arrested; however, 56 percent did not think this would happen.

Because of the diminishing power of PT, many fear the imprisonment of Lula will signal an end to Brazil’s commitment to social justice and equality. It’s conceivable that the anti-corruption backlash stemming from the enormous extensiveness of Lava Jato could open the door to a strong-arm, right-wing candidate like Bolsonaro.

This October we will witness the most unpredictable election in the past 30 years in Brazil. Lula’s conviction has polarized the country in the same way Trump has in the US. However, there is a significant difference between Lula and Trump.

Trump supporters are galvanized by his rhetoric and his promises, but Trump has done nothing concrete in the way of political or economic achievements. Lula’s supporters, on the other hand, cannot be refuted when they lament how much the incarcerated Lula has done for Brazil.

There is no question that Brazil needs powerful leaders to fight political corruption and put an end to impunity. Without justice for the oligarchs, there is no justice at all. What’s required is honest leadership with a commitment to social equality, alongside financial policies to bring jobs back into the economy.

There must be a balance of power between capitalists, socialists, and environmentalists. Strong opposition parties such as PT provide that balance, a way to ensure capitalist policies to keep the economy growing are balanced with heavy infrastructure spending.

Brazil must invest in public education and healthcare, along with rewriting the tax laws making it easier to start and own businesses, and signing international trade agreements to open Brazil’s closed economy.

In the coming years, Brazilians must demand leadership from men and women who have proven their commitment to honest governance. Men like Lula, charismatic leaders, are critical in a dynamic government, even if they represent the opposition party.

B. Michael Rubin is an American living in Curitiba, Brazil. He is the editor of the online magazine, Curitiba in English. www.curitibainenglish.com.br