Brazil abolished slavery 130 years ago, but its society has failed to deal with the crimes that took place. Many Afro-Brazilians remain trapped in a cycle of violence and slave labor, legacies of Brazil’s slave trade.

Evidence of the massive crime remained hidden for a very long time. Before his Italian bride arrived in September 1843, Emperor Pedro II of Brazil ordered the wharf at Rio de Janeiro’s old harbor filled in.

Between 1774 and 1831, some 700,000 slaves disembarked here, more than any other place in the world. Yet the emperor wanted nothing to do with that fact.

Africans who died during the passage to Brazil were often carried up into the nearby hills, where their bodies were thrown into piles stacked between household refuse and dead cows.

In 1996, a family discovered the remnants of this “Cemetery of New Blacks” (Cemitério dos Pretos Novos) under the foundation of their house. The commemorative site they created is now about to be closed. Brazil’s government hasn’t given them a penny in years.

Rio’s Valongo wharf, on the other hand, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site a year ago. The excavated slave docklands are the heart of a neighborhood known as “Little Africa.” It is a model tourist magnet. Still, reminders of slavery seem to be unwelcome on an official level in Brazil, even today.

Forced Decision

The Golden Law, issued by Princess Imperial Isabel on May 13, 1888, officially ended slavery in Brazil. Its abolition came without a bloody civil war as in the United States (1861-1865) or a slave rebellion as in Haiti (1794).

When England prohibited Brazil’s transatlantic slave trade by passing the Aberdeen Act in 1845, Brazilian plantations were faced with a labor shortage. That shortage was compensated with European immigrants, who did not have to fight for their freedom as slaves often did.

Brazil did not end slavery until the economic system it was based upon could no longer be maintained. It was the last country in the Americas to do so. The legacy of 350 years was staggering: Half of all slaves that crossed the Atlantic landed in Brazil; two million of them in Rio alone, another 5.8 million along the coast.

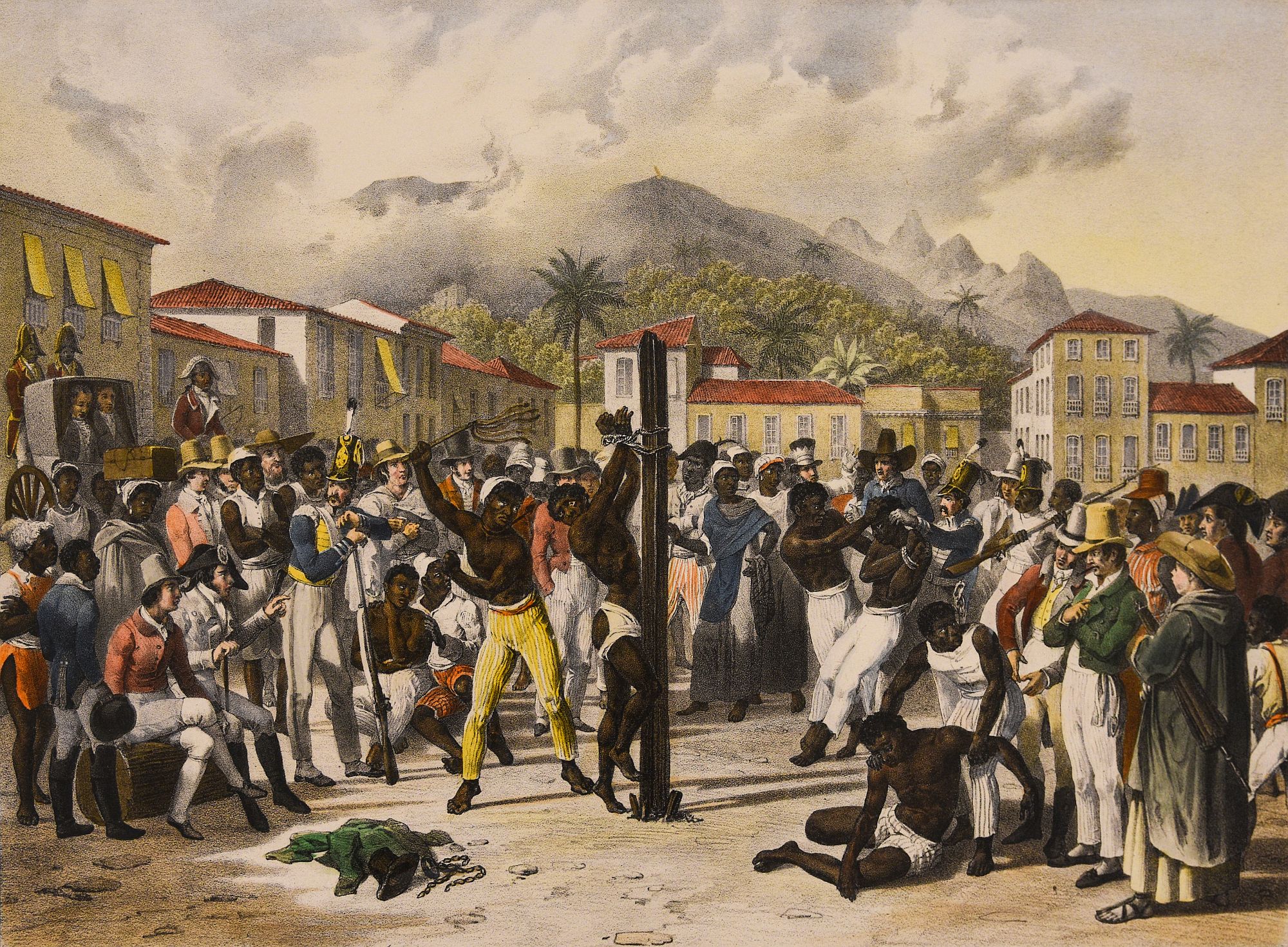

Brazilian plantations exhibited a ravenous hunger for human flesh throughout the era of slavery. It is estimated that 1 in 10 Africans died during the transatlantic crossing. When ships arrived, families were split up.

The men were sent to work the fields of the country’s most remote regions, while the women, raped by their white masters, brought forth generation after generation of new Brazilians. It seems the white masters were not content to exploit nature and man – they dominated their servants literally down to their flesh and bones.

Helplessness Rather Than Jubilation

Despite that, the belief that slavery in Brazil was more humane than elsewhere still persists today. Images and reports from that time – which rarely if ever gave witness to the gruesome reality of the situation – helped create the myth.

When Brazil’s slaves were finally set free in 1888, they faced economic catastrophe rather than experiencing the officially proclaimed jubilation of freedom.

They were simply left to their individual fates – without land, without money and without an education. And that is largely where their descendants still stand today.

Millions of Afro-Brazilians today live in the same precarious circumstances that their forebears faced 130 years ago. The impoverished favela shacks that populate the outskirts of Brazil’s major cities are not unlike those of the 19th century.

Millions of Brazilians have yet to become a welcome part of society. Young blacks make up two-thirds of Brazil’s 60,000 victims of violent crime each year. They also make up two-thirds of the country’s prison population.

Brazil offers them no other perspective than the cycle of violence that is rooted in the age of slavery – namely, rebellion against a hostile society and violence against each other. Whereas whites are as untouchable today as they were back then, black violence in all of its desperation and self-hatred is directed toward other blacks.

The legacy of slavery is not easily shaken off, says Italian psychoanalyst Contardo Calligaris, who has lived in Brazil since the 1980s. He says every Brazilian carries the figure of the brutally dominant “colonizer” and “exploiter” within them.

“Every single relationship in the power structure of Brazil is inhabited by the specter of slavery,” says Calligaris. Power, he says, is also articulated through corporeal dominance – it is the noisy ghost of slavery that refuses to go away.

Modern Slavery

And slavery itself refuses to go away as well. “One still thinks of the Hollywood version of slavery, in which subjects are chained to benches and row under the lash,” says the French Dominican friar Xavier Plassat. “But today people are enslaved by economic dependence rather than chains.”

Since the 1980s, Plassat has been fighting alongside other Catholics against this modern form of slavery. Thanks to their efforts, the Brazilian government passed a law outlawing such modern slave labor in 1995.

Since then, some 54,000 working slaves have been set free. Such people labored in the grazing lands of the Amazon, the illegal sewing factories of São Paulo and the charcoal producing regions of northeastern Brazil for unfair wages.

In 2017, seemingly out of the blue, Brazilian President Michel Temer sought to water down the term modern slavery by removing forced economic dependence as one of its defining criteria. Temer was forced into a quick retreat, however, after he was confronted with a wave of global indignation.

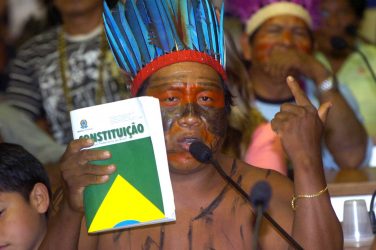

Celso Athayde, an activist in the Afro-Brazilian social movements known collectively as Black Movement, says the cloud of slavery can only be lifted if Brazil’s dark-skinned population finally becomes the protagonist of its own history.

Athayde is the founder of the country’s first political party for blacks, the Frente Favela Brasil. Faced with cries of discrimination from white Brazilians, Athayde points to the country’s samba schools as an example of what happens when predominantly black organizations are opened to whites. Within a very short period of time the whites had taken control of the samba schools. He does not want to see that happen in his political party.

He claims that whites will never be satisfied playing a supporting role, because they want to call the shots. “In contrast, we blacks like to hide behind the whites because we fear playing the leading role. But we need to finally learn how to take the lead.”

DW