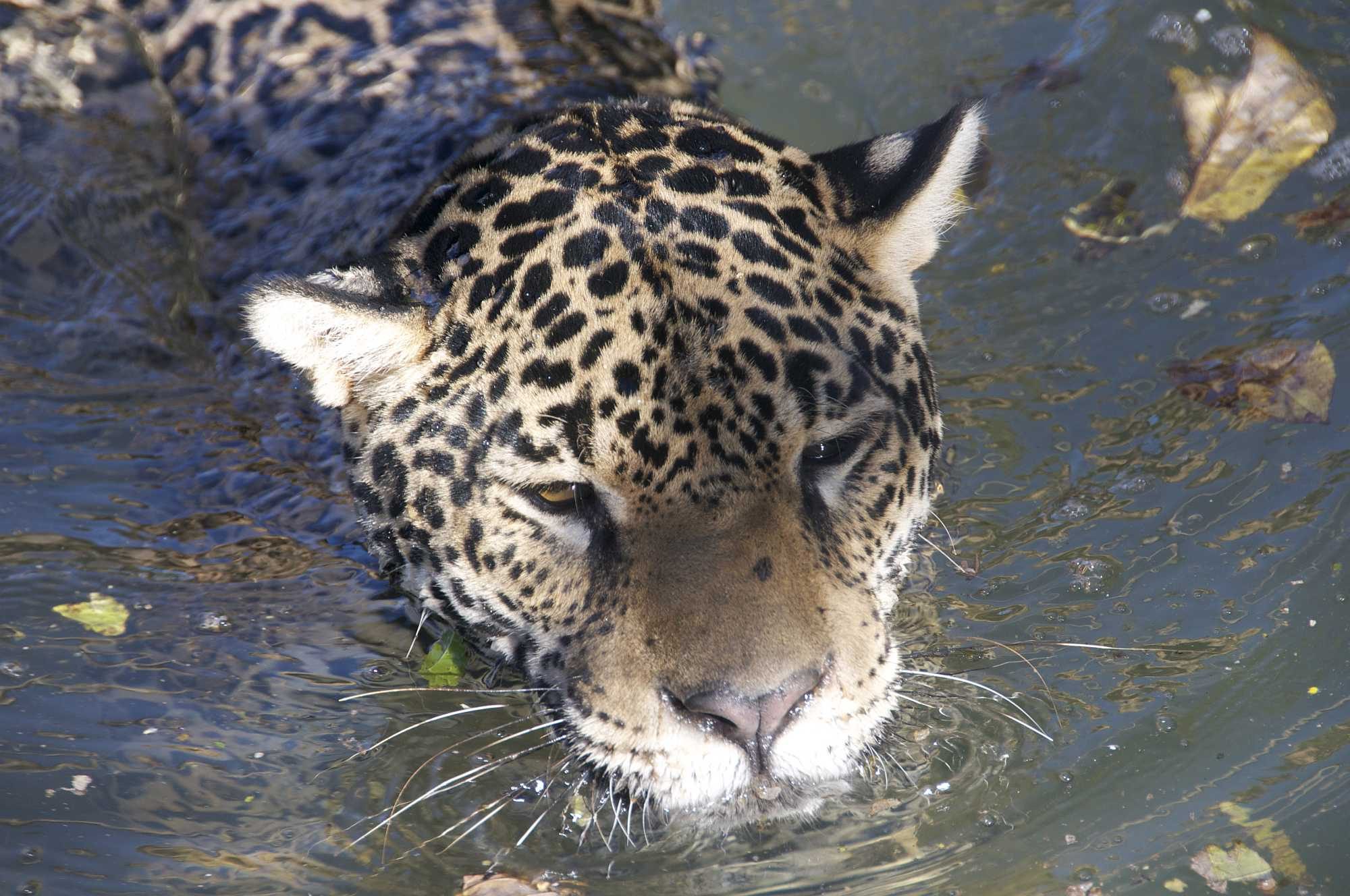

From villain to hero, the jaguar (Panthera onça) stands at the cusp of a radical overhaul in its public image. As the largest cat in the Americas, the species commands a dominant role in the food chain of its native Pantanal – a vast swathe of tropical wetland that encompasses parts of Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia.

Once hunted for its fur, the jaguar’s appetite for the abundant prey in the Pantanal has led it into deadly conflict with ranchers in recent decades, casting it as the stalking menace of livestock and livelihood in a region where much of the land is reserved for cattle rearing.

However, in a hopeful development for conservationists, researchers have revealed in a new study published in Global Ecology and Conservation that jaguars are worth 60 times more to tourism than the cost the big cats inflict on ranchers.

“The study represents a regional reality in the Pantanal,” said Fernando Tortato, research fellow at Panthera, the global wild cat conservation group that helped lead the study. “Where the jaguar brings in far more revenue than the potential damage it can cause.”

Jaguars once abounded from the southwestern U.S. to Argentina, but their numbers have fallen due to hunting and habitat loss. In the Amazon rainforest, deforestation is an ongoing threat, even while the dense foliage often precludes human encounters with jaguars.

In the absence of benign tourism opportunities there is demand for jaguar teeth, paws and claws as souvenirs.

The jaguar’s predilection for lush and low-lying forest makes the Pantanal a stronghold for the species. But wetland’s web-like tributaries also open the wild cat’s home to human exploration, allowing tourists to share in their company.

In the Pantanal, the biggest threat to their survival is conflict with ranchers. To address this tension, the study quantified the value of the jaguar to the growing tourism industry and explored how its benefits could be felt more keenly by those incurring its costs.

Researchers focused on Encontro das Águas State Park, using it as a representative portion of the Pantanal where ecotourism operates near livestock farms. The study defined the total area available here to tourism by mapping the riverside haunts of tagged jaguars that were visible from boats, to give a realistic spatial scale of the costs and benefits of living with the top predator.

The minimum annual income of the tourism industry was calculated from the daily takings of seven lodges operating within this zone. This figure was then compared with a hypothetical estimate of damages to neighboring cattle ranches based on reported jaguar kills and the market value of each bovine.

The difference was startling to the researchers.

“Much greater than expected,” Tortato said.

In comparison to an estimated yearly loss from cattle depredation of US$ 121,500, the researchers found the jaguar tourism sector was taking in a gross annual income of around US$ 6.8 million.

Even then, they write that their potential revenue estimate was conservative – it only accounted for the earnings of established lodges within a specific portion of the Pantanal, not the entire host of smaller outfits operating there and elsewhere.

Knock-on benefits to local businesses from tourists passing through the Pantanal were also not included, so the researchers say the full economic value of jaguar ecotourism is likely far greater.

For conservationists, however, the study brought even better news.

“What surprised us was the interest of tourists,” Tortato said. “Tourists who visit the Pantanal in search of jaguar are willing to pay for damages, and this reaches the root of the conflict, creating a pragmatic solution to the cattle losses of ranchers.”

The researchers reckoned that the cost to cattle ranchers could be met with a one-off donation of US$32 per tourist. But their findings showed that 80 percent of tourists were happy to pay almost three times as much. Over a three-day stay, most were willing to donate an average of US$84 to a compensation scheme for inconvenienced ranchers.

The study indicates that, if rolled out region-wide, the scheme would more than offset the costs of a thriving jaguar population, laying the groundwork for landscape-scale conservation that could overcome present barriers of private land ownership.

Interaction between jaguars and cattle is likely to remain inevitable in the Pantanal, where over 90 percent of the territory is privately owned and overwhelmingly used for rearing livestock. Only five percent is protected today.

Despite the local dominance of ranching, however, jaguars are entwined in the ecology and culture of the region. As an apex predator, they play an important role in the population dynamics of their prey, which include caimans, capybaras and deer.

“In the process, they regulate the transmission of disease between these species, and from them to domestic animals and even man,” Tortato said.

In Pantaneiro folklore, the jaguar is a talismanic symbol of the wilderness – an enduring relic of the region’s exciting and untamed past. From this, the idea of a new source of income sprung forth in one community.

The Ribeirinhos are local people who inhabit the Pantanal’s riverbanks. Many rely on communal knowledge of the rivers to navigate tour boats for visitors. Usually poorer than their landholding compatriots, Ribeirinhos have profited from the new industry that has emerged on the backs of their once-feared enemies.

“Today the jaguars are benefactors,” Tortato asserted. “They’re helping poor river peasants to reach a higher socioeconomic level or better their education, thanks to the employment opportunities provided by jaguar-oriented tourism.”

The experience of one jaguar tour provider seems to lend support to the study’s conclusion that a reward system levied by tourists could promote harmony.

Dr. Charles Munn has been compensating a local cattle ranch for the last seven years and describes the scheme as “spectacularly successful” and responsible for maintaining an “extremely good” relationship between his business and neighbors.

Munn owns SouthWild – a South American-based wildlife tourism company. In addition to his compensation scheme, he claims several “firsts” for Pantanalian ecotourism, such as “the jaguar guarantee.”

“Give me three nights and four days and if you don’t see a jaguar in the day time, I pay back the entire cost.”

Since 2005, he said he has only had to refund customers twice.

“We have jaguar boat drivers with 5,000 hours of face-time watching wild jags with guests, which probably is 10 times more – maybe 20 or 50 times more jag face-time than all biologists have had in the history of our planet.”

The success of SouthWild is one of the reasons why Munn believes the true value of the jaguar is far greater than the study’s estimate. Fifty regular jaguars make up most of Munn’s sightings in a 100-kilometer tract of the Brazilian Pantanal and Munn claims each big cat is worth around US$ 1 million to the country’s economy.

From windfalls for national airlines to a flow of foreign tourists with disposable income, the returns from what Munn describes as “Jaguarland” easily dwarf the costs of cattle depredation. However, despite the enthusiasm surrounding the industry, Munn notes a hesitance by the local government to engage with it.

“In 2006 I proposed that all my guests pay a conservation fee…the state government said that they appreciated the effort but could not accept any donations until there was a written management plan.”

Tortato and his team also argue that greater state involvement could help unlock the full potential of ecotourism for jaguars and people.

“The lack of management, supervision and taking advantage of the financial opportunities offered by protected areas in the Pantanal limits their potential for public use.”

Among its other recommendations, Panthera has advice as to how the proposed donor fund could work in practice, from rewarding landholders for protecting jaguars on their property and regulating hunting so that there is sufficient wild prey for the top predators to ensuring cattle are managed in ways that deter jaguar predation.

Jaguars are “smart,” Tortato said, and any measure would never completely end predation on cattle. But he says they could one day make jaguars a lesser concern than other causes of cattle mortality, such as snakes or disease.

With characteristic zeal that seems to embody the optimism of this new industry, Munn claimed that jaguar tourism is poised to take off – with ensuing benefits for human and wildlife communities in the Pantanal.

“A thousand high-quality jobs have been created already in Brazil by these 50 jags,” Munn said of the big cats his company depends on. “The biggest new source of nature-related jobs in Pantanal since 1960…and jag tourism is just in diapers, it could grow by a factor of 100 in the next 10 years.”

Citation:

Tortato, F. R., Izzo, T. J., Hoogesteijn, R., & Peres, C. A. (2017). The numbers of the beast: Valuation of jaguar (Panthera onça) tourism and cattle depredation in the Brazilian Pantanal. Global Ecology and Conservation, 11, 106-114.

This article appeared originally in Mongabay – https://news.mongabay.com