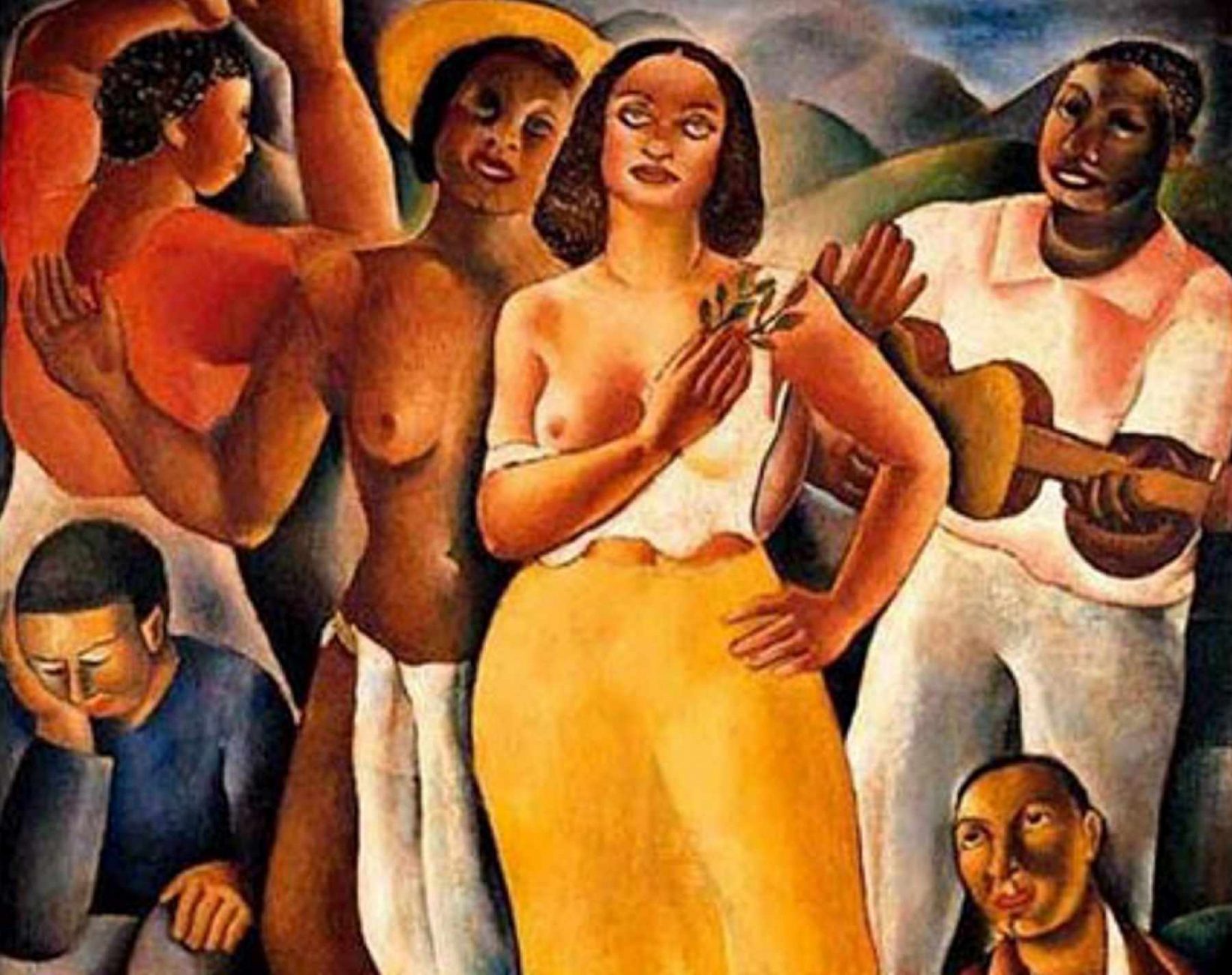

As the world gets into the Carnaval spirit, we look at how Brazilian music has contributed to the fight for social justice.

The famous Brazilian rhythm of samba, the soundtrack to annual Carnaval festivities, has been more than just a reflection of the happiness and celebration the South American nation is known for. It has also been a form of activism against repression in Brazil.

For decades, several artists have used samba music to express their opinions on the social, economic and political issues in the country. Artists who were censored during the country’s dictatorships managed to pass along their political protest messages disguised as happy tunes.

During the military dictatorship of General Getúlio Vargas in the 1930s, the government used the development of samba as a way to unify Brazilian culture.

As escolas de samba (samba clubs) expanded, Vargas used the style of music to wash away any signs of social struggle. The dictatorship prohibited any criticism during the parades to prevent any awareness of class struggle by the poor.

Then, during the military dictatorship of the 1960s and ’70s, samba music became a symbol of resistance. One of the main artists who became a worldwide figure for his lyrics and music is Chico Buarque, who mixed popular culture and poetry to criticize human rights abuses in the country.

After the 1964 military coup in Brazil, Buarque began writing social and political songs, which were in return censored. He began using analogies, puns and subtle references to avoid censorship.

Buarque was arrested in 1968 and lived in exile in Italy in 1969. He returned to Brazil in 1970 and continued writing songs as a protest against the dictatorship.

One of his songs, called “Despite You,” has become a hymn for social struggles. The lyrics say:

“Today you are the one who rules / What you say is a fact / There is no discussion / Today we are talking secretly / And looking at the floor / You who invented that state / And invented all obscurity / You who invented sin / Forgot to invent forgiveness.”

Another one of his popular songs, “Calice,” talks about a biblical story, but it really refers to the military repression. He plays with the Portuguese word “cale-se,” which means shut up, and the religious “chalice.”

One of the verses says: “How to drink this bitter drink / Swallowing the pain, swallowing the hard work / Even if the mouth is silent / Silence in the city is not heard / What’s the use of being a saint’s son? / It would be better to be the other’s child /Another less dead reality / Such a lie, so much brute force.”

Carnaval 2017

Carnaval celebrations began on Friday in Brazil, drawing thousands of costumed revelers to block parties in 32-degree Celsius (90 degrees Fahrenheit) heat.

Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets on Saturday for Rio de Janeiro’s oldest and biggest block party, the Bola Preta. In the past, the “Black Ball” has drawn up to 1 million revelers dressed in black and white to Rio’s historic center.

The five-day festival is expected to generate an estimated US$ 1 billion in revenue for Rio, but the celebrations began on an odd note when the city’s deeply religious mayor didn’t show up for the starting ceremony on Friday.

After delaying the start of the ceremony for two and a half hours in the Sambodromo stadium, Mayor Marcelo Crivella never came. Instead, the city culture secretary arrived to give the Carnaval king or “Rei Momo” the ceremonial key to the city.

When asked why Crivella, a retired evangelical bishop, did not attend, the culture chief said: “His wife is sick.”

In Salvador, an enormous crowd gathered on Saturday to hear musicians Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso sing as they celebrated 50 years of the Tropicalia musical movement that they started.

São Paulo, Brazil’s business capital, party-goers clogged traffic while its Carnaval parades made their way down a main city avenue.

Celebrations will continue across the country until Tuesday.

Old Tunes for Pain

Several musicians go to a hospital in São Paulo and play old songs for the terminally ill to calm their pain and suffering.

Sebastiao gasps, unable to control his breathing, but suddenly the sounds of a flute calm his discomfort. They are the chords of a song he remembers from long ago, played by one of the musicians dedicated to alleviating the suffering of patients being treated for their pain at a Brazilian hospital.

“When I first came here there were about 13 people in the ward. Sebastião wore an oxygen mask and breathed with great difficulty, very fast. But when I started playing his breathing calmed down in 10 seconds. Everybody started crying and I almost cried myself,” Brazilian flutist Antonio Carrasqueira told reporters.

Antonio’s story is one of the many emotional accounts told by musicians who every week go to São Paulo’s Premier Hospital, not to play songs from their own repertoire but rather songs that the patients remember from long ago.

Several years ago Samir Salman, director of the clinic for those suffering degenerative diseases or for seniors who need pain relief, decided to include music in the “hospital’s strategy, as one more therapeutic treatment.”

“The idea is that the musician brings back the patient’s musical memories with the help of the medical staff and the sick person’s biography,” he revelade.

teleSUR/DW