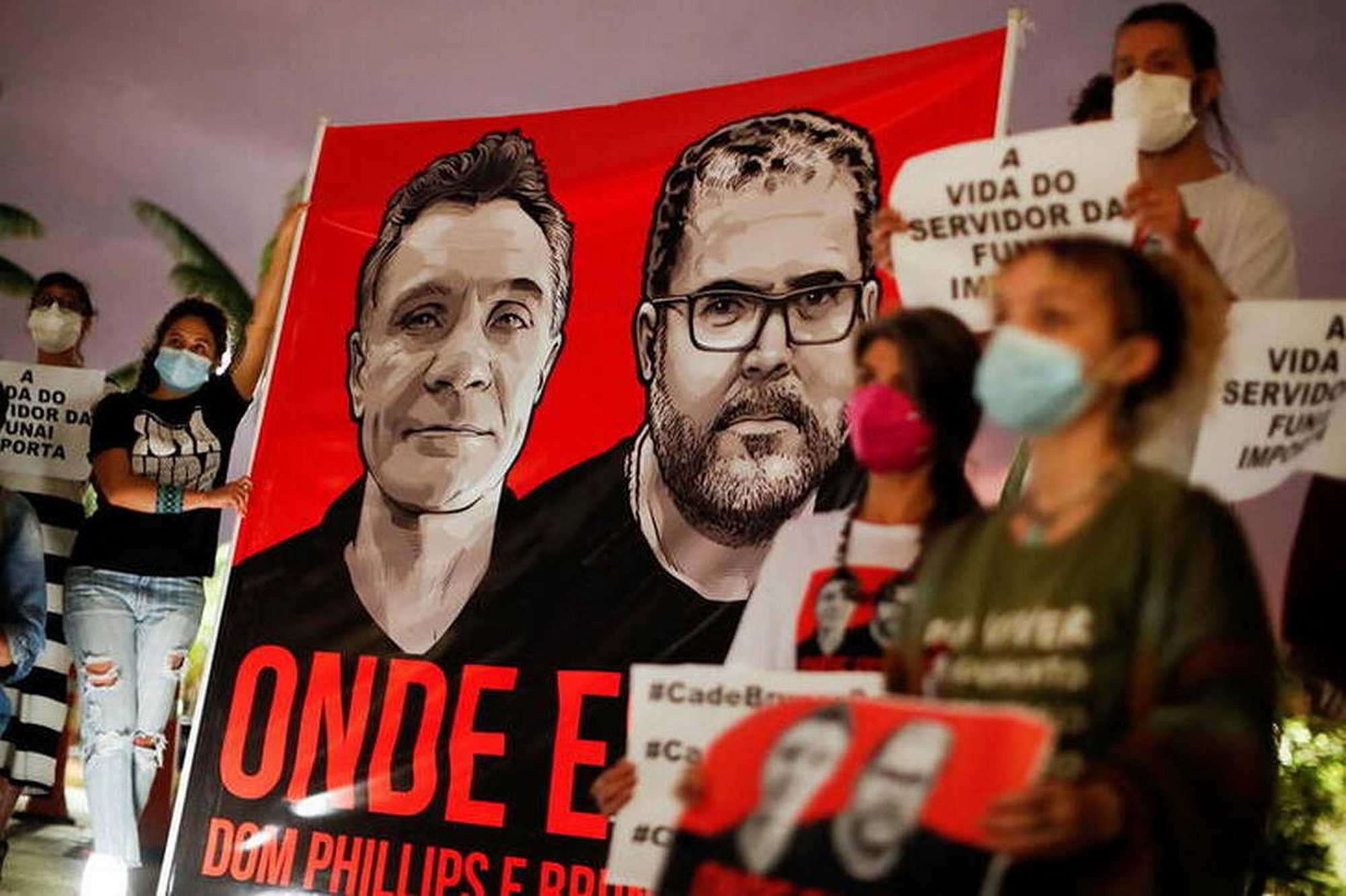

Sent to a desk job after President Jair Bolsonaro’s election, indigenous protector Bruno Pereira took leave and returned to the field – but is now missing with British journalist Dom Phillips

Until far-right Jair Bolsonaro took office as Brazil’s president in 2019, missing Amazon expert Bruno Pereira coordinated efforts to protect isolated indigenous people at Funai, the government agency in charge of protecting native peoples.

But as Bolsonaro made good on a campaign pledge to take a “scythe” to Funai for its role in formally recognizing more indigenous territories, Pereira was taken off field activities and replaced with an evangelical missionary.

Pereira – like some other colleagues sidelined at Funai – found his way back to the work he felt passionate about, taking leave from his government job to return to the frontline of indigenous protection: the remote Amazon Javari Valley.

The 41-year-old had already worked as a Funai coordinator in the Javari Valley reserve, the country’s second-biggest indigenous territory.

On June 5, Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips, who was researching a book there with Pereira’s guidance, disappeared along with their boat, a day after Pereira was threatened by an illegal fisherman in the area.

A threat letter accused Pereira of “telling the Indians to arrest our motors and take our fish”. A fisherman is under investigation in association with the pair’s disappearance, police said.

A television channel quoted Phillips’ wife on Monday as saying the two men’s’ bodies had been found, but Brazil’s federal police denied that, saying only that items belonging to the men had been recovered in a river near where they disappeared.

Both were veterans of travel in the remote valley near the Peruvian and Colombian borders, home to the biggest concentration of Brazil’s remaining isolated and uncontacted indigenous tribes.

But under what analysts say is a weakened Funai, indigenous areas in the “wild west” of the Amazon have faced worsening incursions by land grabbers, gold miners, illegal hunters and fishermen and drug trafficking gangs.

‘ANTI-INDIGENOUS’ AGENCY

On Monday, Indigenistas Associados (INA), an institution that represents Funai agents, released a dossier in partnership with the Institute of Socioeconomic Studies, a nonprofit Organisation focused on public policies, accusing Bolsonaro’s government of persecuting public employees such as Pereira and transforming Funai into an “anti-indigenous” agency.

The document said Bolsonaro had carried out his threats to weaken Funai and not recognize “one more centimeter” of indigenous land with formal protection.

The changes have put indigenous communities – and those who work to protect them, such as Pereira – at greater risk, said Fernando de Luiz Brito Vianna, president of INA and one of the authors of the dossier.

In response to the charges in the dossier, a Funai spokesperson said that the agency “acts in strict obedience with the principles of legality, impartiality and morality” and that its work is in the public interest.

Charges of persecution of agents within Funai were unfounded, the spokesperson added, noting agency heads had the right to hire and fire directors and other key staff as they wished.

According to the dossier, career Funai officers have been sidelined since Bolsonaro’s election and replaced with people with far less experience of indigenous matters.

Of 39 coordinators currently working in the agency, 17 are military officials, five are police officers and six have no previous experience in public administration, it said.

Pereira was replaced as coordinator in 2019 shortly after dismantling illegal mining operations in the Yanomami indigenous reserve, part of his efforts to protect uncontacted indigenous groups at Funai.

After taking leave from Funai, he went on to support the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley (Univaja), teaching activists to operate drones and map and document crimes to report them to authorities.

FRUSTRATIONS

Two former colleagues of Pereira at Funai, who were not given leave from the revamped agency and quit to continue their indigenous work with nonprofits, said they understood the frustrations that took Pereira back to the Amazon.

“I left Funai a year ago after asserting that the indigenous policy was being dismantled,” one of them said, asking not to be named.

The former employee quit after fearing “I would be called to take part in a disciplinary process against a colleague” who was pushing ahead the agency’s indigenous protection work, they said. Another said they did take part in such a process.

Four indigenous protection agents still working with Funai said staff who remained at the agency have faced ongoing pressure to change the way they do their jobs.

“We are considered opposition … we are ostracized or treated as untrustworthy,” said one Funai agent, speaking on condition of anonymity.

According to the dossier, agents have been told not to use terminology deemed “subversive” by Bolsonaro’s administration, which can include terms such as “indigenous movements” or “indigenous assemblies”.

One source in Funai said staff have been told to avoid using the term “peoples” – seen as leftist – for indigenous groups.

In a similar vein, the red logo of Brazil’s Indian Museum in Rio de Janeiro – its color inspired by a symbol of the indigenous Kadiweu people – was switched to blue, to avoid a “leftist” color.

Other Funai field agents were transferred to administrative work in Brasilia or “left in the fridge” after doing work contrary to the government’s new vision, another Funai agent said, also requesting anonymity.

Last year, a report by Funai agents that recommended maintaining protections for indigenous groups in an area where signs of isolated populations had been spotted was internally classified as “ideological” and “unsuitable”, the dossier said.

FARMERS AND LAND GRABBERS

On several occasions, Funai’s president, Marcelo Xavier, not only questioned studies developed by agents but reported them as misconduct to Funai’s internal affairs department and the Federal Police, the dossier said.

Xavier did not respond to requests for comment.

A Federal Police agent, Xavier comes from a family of farmers. In 2014 he was removed from police operations aimed at driving farmers out of indigenous land after wire-tapped farmers said he was on their side, the BBC reported.

He is backed by Brazil’s powerful agricultural lobby in Congress, which frequently opposes the recognition of indigenous territories, underscoring Funai’s transformation under Bolsonaro, analysts say.

“You have now in Funai people who three years ago were preparing documents favorable to farmers and land grabbers,” said Ricardo Verdum, who is a member of the Indigenous Issues Commission at the Brazilian Association of Anthropology.

Under the current administration, Funai has pressured the indigenous Waimiri Atroari people to reestablish talks about the construction of a long-distance electrical power line across their territory, the dossier said.

Xavier also moved to limit the agency’s protection efforts only to areas formally recognized as indigenous territories – a position later partially reversed in February 2022 by the Supreme Court.

Currently, 123 mostly Amazon territories covering 10.57 million hectares are undergoing the often decades-long process of seeking official recognition as indigenous land, according to data from the Instituto Socioambiental, a nonprofit focused on defending the environment and traditional communities in Brazil.

Another 118 territories are in the first phase of study by Funai, which is responsible for identifying the total area they cover.

Funai’s decision under Bolsonaro to protect only officially recognized indigenous land effectively helped open traditional indigenous areas not yet afforded formal protection to invasion by non-indigenous settlers, said INA’s Vianna.

Funai has seen its mission reversed under Bolsonaro, said Leila Saraiva, political advisor of the Institute of Socioeconomic Studies and co-coordinator of the dossier.

“The government is doing more than leaving Funai inactive … it is stealing it to defend anti-indigenous interests,” she said.

Vianna said he believed change at Funai would come only with a change of government, as Brazil heads toward elections in October.

Polling published in late May by agency Datafolha showed leftist former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva leading Bolsonaro in the race, with 43% of the vote to Bolsonaro’s 26%.

Andre Cabette Fabio is a journalist based in Brazil for the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

This article was produced by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Visit them at https://news.trust.org/