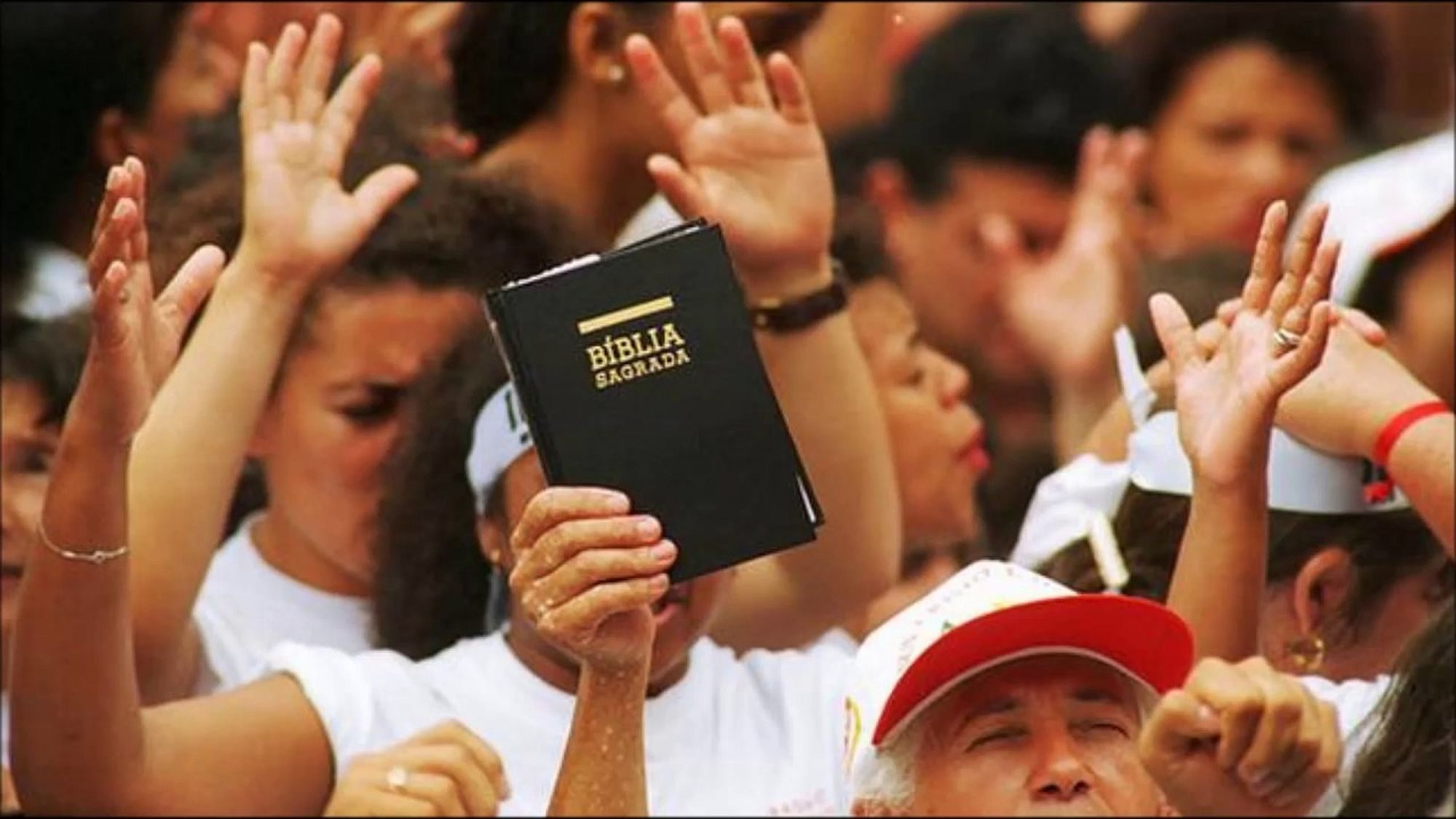

The influence of the Catholic Church has waned in Brazil, where people have been flocking to evangelical churches. Now these churches have their sights set on the presidency, signaling a possible shift to the right.

Brazil once had the reputation of being the most Catholic country in the world. With the exception of General Ernesto Geisel, an evangelical Christian who ruled the country from 1974 to 1979 during the military dictatorship, Brazil has only ever had Catholic heads of state.

However, the upcoming presidential election on October 7 sees two candidates with an evangelical profile — Marina Silva and Jair Bolsonaro — vying for the highest office in the land.

Silva, an environmentalist, is a convert from Catholicism who joined an evangelical church several years ago. Bolsonaro, actually a devout Catholic and often called Brazil’s Donald Trump for his outrageous views and focus on law and order, was baptized in the Jordan River by an evangelical preacher in 2016.

For decades now, people have been flocking to Brazil’s Evangelical Protestant and Pentecostal churches. Around 42 million Brazilians (22 percent of the population) registered as “evangélicos” in the 2010 census, while around 123 million (64 percent) described themselves as Catholic.

Experts estimate the number of “evangélicos” is currently at around 30 percent, yet they are still politically underrepresented. A cross-party federation of evangelical politicians says only about 100 of the 513 representatives in the lower house of parliament belong to the “frente evangélica,” founded in 2003.

According to media reports, only five of the 81 senators in the upper house of Congress are evangelical.

Viable Competitors

In the upcoming election, that number could increase by at least 10 percent, “thanks to a good performance by the candidate Jair Bolsonaro,” said Ricardo Ismael, a political scientist at the Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. “What’s new is that the evangelicals are becoming viable competitors in elections to the executive branch.”

The election of Marcelo Crivella as mayor of Rio de Janeiro in 2016 set the pattern. Crivella, a bishop in the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, had the might of a Pentecostal church behind him; it was founded by his uncle, Edir Macedo, who also owns a TV station called Rede Record.

Its pastors are reported to have drummed up support for Crivella in their sermons. It’s not known how much money the church contributed to his costly election campaign.

Not all evangelical candidates are backed by such rich, influential churches. But they are winning voters from the new lower middle class, whose numbers greatly increased under the government of the Workers’ Party, in power from 2003 to 2016. “Many low-income earners and lower-middle-class people felt the promises of the evangelical neo-Pentecostal churches spoke to them,” said Ismael.

Seeking Moral Rigor

Francisco Borba Ribeiro Neto, of the Catholic University of São Paulo, sees the rise of the evangelicals as a consequence of the rural exodus in the second half of the 20th century. In the cities, this deeply religious rural population encountered a secularized, permissive, Catholic urban society — and took refuge in the morally stricter, more conservative and purist evangelical Pentecostal churches.

“For a population that was suffering in terrible living conditions, in shock at losing their traditional values and feeling lonely in the big cities, their message was very attractive,” he said.

In recent decades, this formerly rural population has been particularly successful in advancing economically to become part of the new middle class — and it now tends to vote for right-wing conservatives. Opinion polls show that evangelical voters are considerably less likely (6 percent) than Catholics (21 percent) to vote for left-wing parties.

“The Catholic discourse focuses more on social issues, the rights of the poorest in society,” said Borba Neto. “Meanwhile, the evangelical discourse — and particularly that of the neo-Pentecostal churches — concentrates on moral values.”

Evangelical Head of State?

Unlike the poorer classes, who depend on welfare assistance and tend to vote for the left wing, people who have moved up into the lower middle class no longer rely on aid directly provided by the state.

“The neo-Pentecostal churches occupy a hegemonic position in this new middle class, in which they concern themselves with moral values, fight against the lack of security in cities and call for an end to the welfare state — which is no longer relevant to their needs,” said Ismael.

Furthermore, he said, the vast majority of evangelical politicians reject the agenda of left-wing minorities. “The evangelical parliamentary group has positioned itself against a left-wing agenda that advocates more rights for minorities, for new family models calling for a debate around gender issues and the education system,” said Ismael. “It’s still too early to say whether they will be successful in blocking this agenda. But they do have the power and the influence to have a say.”

The latest presidential opinion polls show Bolsonaro in the lead at 28 percent, with Silva trailing far behind at 5 percent. “Bolsonaro reproduces evangelical sermons in his discourse, adopting a stance against the left-wing agenda in questions of traditions and customs,” said Ismael. “This is why he has such high approval ratings among evangelicals.”

Silva, on the other hand, doesn’t limit her discourse to evangelical sermons, instead putting an emphasis on social policy as well as environmental protection. “Oddly, Marina Silva is an ideal Catholic candidate, although she is divided in her views,” said Borba Neto. “She’s left-wing on social affairs, and closer to the right on issues of morality.”

Bolsonaro, by contrast, represents par excellence “the ambition of the new middle class. For both evangelicals and ultra-conservative Catholics, Bolsonaro is the populist alternative — a leader who professes that, if necessary, he’ll go it alone to deal with problems that cannot be resolved by democratic dialog.”

DW