Since the election victory of Donald Trump, many have tirelessly talked about populism. It is not a first appearance. This phenomenon has been recently experienced in Latin America, it has also been the spirit of the interwar period of fascism in Europe and it has happened in Russia in 1917. In fact, it has happened many times, in many different places.

Since the emergence of so-called left-wing populism in Greece and Spain, with SYRIZA and “citizen platforms” in union with Podemos, up until more recent right-wing populism from the National Front in France, Donald Trump and the Alt-Right, and Brexit and the UKIP, Geert Wilders (in addition to Austria, Hungary, Switzerland, Norway) etc, the “western” world seems to be haunted by the specter of populism.

Finally, has Brazil, which lived its personal drama between the reelection of Dilma Rousseff (November 2014) and her impeachment (August 2016), also achieved this international trend?

Crisis, House of Cards, and More Crisis.

In Political Science, especially in International Relations, a large technical vocabulary is used to refer to Brazil’s position in the International System. It has varied recently from the euphemistic use of the term “peripheral nation” to the ambitious “emerging power.”

In both cases attention is drawn to the geography and mechanics used. It is almost unnecessary to point out that these are relational terms. Someone is peripheral to something or someone, as well as who emerges, does so from one environment to another.

It is derived from this physics that waves originating in the “center” propagate to the “periphery”, as well as that turbulences in an environment can transfer to a neighboring environment.

President Lula da Silva, for example, referring to the 2007-08 Financial Crisis, once said that it was a “tsunami” in the United States, but Brazil would only have a “marolinha” (a wavelet). History proved him wrong, but the analogy still holds some value, after all something arrived in Brazil at last, although late.

One can propose another vision for the mechanics envisaged by Lula if only we look back at the major historical events of the last century. Namely, that the great historical characters and facts, according to Marx, seem to repeat themselves – first as tragedy, then as farce.

Does this mean, for instance, that the tragedy of the 1929 Crisis and its “superstructural” (political and ideological) effects on international politics, of a transnational populist “moment” in the 1930s and 1940s simply returns today as a farce? Difficultly.

World political history does not seem to follow a single unvarying and identifiable flow. In fact, those who are well acquainted with history and politics in general know that there are flows and reflows, movements and counter-movements, revolutions and counter-revolutions.

But the ebbs don’t ever mean a return to the exact previous status quo, but rather a dialectical and historical overtake. The “movement” of history, therefore, is more like a war of position, of trenches, of gains and losses, rather than a frontal, immediate and unequivocal irruption, as Gramsci would say.

Yet, just as so-called “right-wing populism” spread throughout the European scene of material scarcity and personal hopelessness in the first half of the last century, something similar (but not the same) is happening today in Europe itself and in the United States. But how has the “wavelet” arrived in Brazil?

Let us make a rather superficial summary of the last years of Brazilian political life, justified only by the impracticability of dealing fully with the historical conformation of the Brazilian crisis conjuncture.

In 2010, Dilma Rousseff (PT) is elected president after running against José Serra (PSDB) in the second round. In her campaign, Rousseff presents herself as a continuation of her and President Lula’s party policies (such as the welfare program Bolsa Família, which aimed at providing financial aid to poor Brazilian families on condition that children attended school and were vaccinated) – as Lula leaves the presidency with a record approval rating of 87%.

What followed was a slowdown in the Brazilian economy during her first term (2011-2014), a desertion from the counter-cyclical measures taken by the PT government since the end of the Lula administration to combat the international crisis and finally the great protests of June 2013 (Jornadas de Junho).

Nevertheless, Rousseff is re-elected at the end of 2014, defeating Aécio Neves (PSDB), also in the second round, with a difference of only 3% of valid votes.

From the beginning of 2015 onwards, what took place was politics in its purest form. In addition to a dramatic intensification of the effects of the international crisis in Brazil (greater than a wavelet), Brazil experienced an endless series of unpredictable events of greater drama than the Latin American soap operas themselves.

In short, it was part of the everyday life of the Brazilian citizen (and it still is), when opening the newspaper in the morning, to come across: Some new arrest of a high-influence politician or a billionaire from the construction industry as a new phase of Operation Car Wash (Operação Lava Jato).

Some new plea bargain agreement that compromises politicians of almost every party. Conspiracy theories involving people of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Leaks from secret audio recordings of these same people which would prove right or wrong some of the theories. Accidents and tragic deaths of key figures in the investigations.

More conspiracy theories. Motions for impeachment directed to the President of the Republic (Dilma Rousseff). Motion to remove the President of the Chamber of Deputies (Eduardo Cunha, PMDB) who ironically had just accepted the motion against Rousseff and eventually got arrested by Lava Jato.

A suspension order issued by Justice Mello to the President of the Senate (Renan Calheiros, PMDB) who simply decided to ignore it. Impeachment motion directed to the governor of Rio de Janeiro (Luis F. Pezão, PMDB) and the arrest of two former governors of the same state (Garotinho, PR, and Cabral Filho, PMDB). Protests against the government. Protests supporting the government.

Finally, an almost endless chain of events resulted in the Senate vote in August 2016, for the removal of Dilma Rousseff from office. This marks the start of then Vice President Michel Temer’s (PMDB) presidency, raising a heated public debate about the legitimacy of his government.

Populism in Brazil: There and Back Again

On February 15, 2017, the National Transportation Confederation (CNT) and the MDA Research Institute announced the results of their poll regarding voting intention for the 2018 presidential elections: Lula da Silva (PT) leads with 30.5%, followed by Marina Silva (REDE) with 11.8% and, most impressively, Jair Bolsonaro (PSC) with 11.3%.

What is surprising? The accumulation of forces of right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro. Although it’s true little attention has been given to Marina Silva, this is justifiably so. Silva is a former senator from the Amazonian state of Acre, with moderate or unclear positions on most major political issues.

Located at the center of the political-ideological spectrum, Marina Silva is affiliated with the hardly relevant REDE, a party with environmental outfits, but with little theoretical formulation or practical action.

The senator’s performance most likely results from her performance in the 2010 and 2014 presidential elections, ranking third in both and presenting herself as the “middle way” between left and right.

Her seasonal appearance every four years in Brazilian electoral politics usually fails to build up momentum and hardly presents her as a viable political alternative.

The 30.5% obtained by Lula does not fail to impress. As it is widely known, Lula was president of Brazil for two terms: 2003-2006 and 2007-2010. His name is both the most controversial and the strongest of the current political left in Brazil. The progressive field also counts on probable candidates that are critical of Lula.

Namely, Ciro Gomes (PDT), former governor of the state of Ceará, a national-developmentalist, owner of an eloquent and aggressive discourse. Lastly, it is likely that a new candidate will still be announced by PSOL, a party that is more ideological than PT and PDT, but of little strength outside the intellectual and academic circles.

The big news, however, is the inclusion of Jair Bolsonaro in the list. His rise to third place outperforms all other leaders traditionally associated with the political right, such as former candidates Aécio Neves and José Serra (both from PSDB).

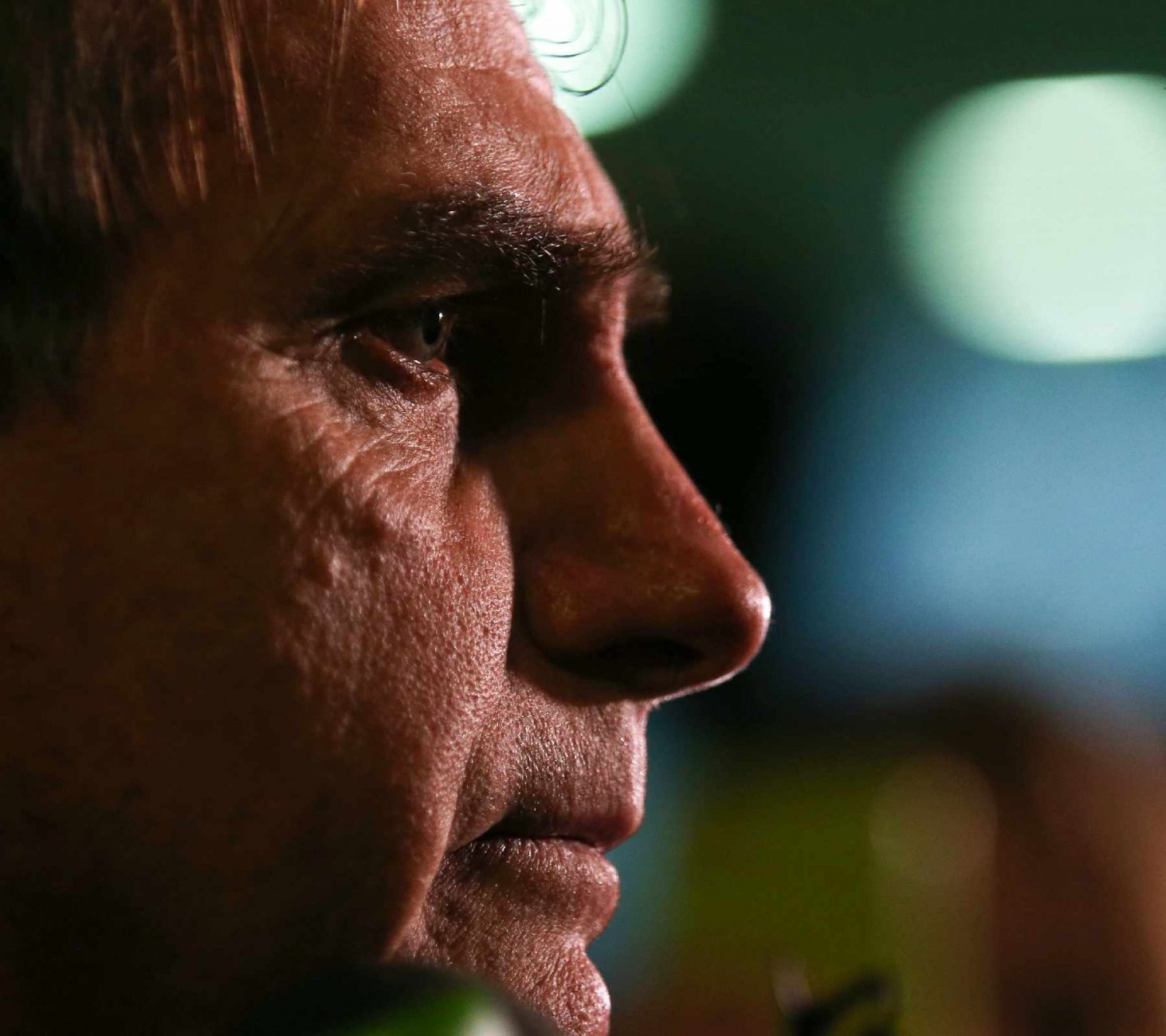

But who is Bolsonaro? Member of the Christian Social Party (PSC), Bolsonaro is a former captain of the 8th Artillery Group of the Brazilian Army, a federal deputy for the state of Rio de Janeiro and father of the also politicians Eduardo, Flávio and Carlos Bolsonaro.

The Bolsonaro family, in general, is unquestionably associated with far-right ultraconservatist politics and they carry out polemic statements ranging from the defense of the Military Dictatorship in Brazil (1964-85), to positions considered intolerant, sexist and homophobic.

In 2015, for example, when asked about an Amnesty International study of the country’s public security crisis (in 2014, more than 3,000 people in Brazil were killed by the police), Jair Bolsonaro literally stated:

“I think the Military Police of Brazil should kill more”. It is unnecessary to clarify that Bolsonaro is critical of the notion of Human Rights and regards it as the creation of socialists seeking cultural hegemony.

In this electoral framework, with no intentions of underestimating Marina Silva, what strikes the attention is the dispute between the populism of Lula and that of Bolsonaro. Is it an “old” populism of the South American Pink Tide against a “new” far-right populism? What do they have in common? And more importantly – what is populism?

Definitions and Non-definitions

Many definitions and interpretations have emerged or been recalled since Donald Trump’s victory. Namely, in December 2016, after the outcome of the American presidential election, Time magazine devoted an entire article, “The Populists” by Simon Shuster, to deal with the populism of Donald Trump and Nigel Farage (UKIP), however, without caring about defining or explaining the phenomenon.

This lack of conceptual clarity on populism is not exclusive to Time. As Ernesto Laclau explains in his book “On Populist Reason” (2005), most of the time, intellectual understanding is replaced by appeals to an “unspoken intuition” or by descriptive enumerations of a variety of “relevant characteristics”.

Appealing to intuition and enumerating “relevant characteristics” is precisely what Forbes does, in its January 24, 2017 article entitled “Why Populism Is Rising and How To Combat It” and signed by IESE Business School.

Astonishingly enough, the article begins with the statement: “Readers relax, I’m not going to talk politics.” What follows are some painful paragraphs of pure ideological verbiage and, finally, a list of characteristics that, in short, associate populism with a deviant practice that divides people between “us” and the “elite”.

Examples multiply. We could also mention the part of the specialized media that tried to deal with the subject with less common sense. Foreign Affairs, in the article of the well-known Fareed Zakaria “Populism on the March” of November/December of 2016. Zakaria points out to economic factors are not the most important to explain contemporary populism, but cultural factors are.

Problems arise here concerning the idealistic ontological foundations of Zakaria. Why, for example, is populism manifesting only now if the cultural components of Western democracies have not changed since the recent past, and more importantly, if these cultural components have recently changed, what made that happen?

We are finally left with a definition that seems to embrace the different types of populism in geography and history as well as to understand it from a process that is historical, conjunctural and comprises changes.

On November 9, 2016, Pablo Iglesias, Secretary General of the Spanish left-wing party Podemos (and a populist himself), describes populism in his article “Trump y el momento populista” in his column “Otra Vuelta de Tuerka” at “Diario Público”.

According to Iglesias, populism is not an ideology nor a “pack of public measures”, but rather it is a way of constructing the political from an “outside” which expands in moments of crisis.

He also claims that populists are outsiders and they can be located anywhere on the political spectrum. However, that should not suggest that the “extremes” (right and left) join together or are similar in any way.

“Trump is not close to Sanders”, Iglesias explains. Rather, Trump’s immigration policies are close to the ones of the Republican Party and the European Union. Therefore, populism doesn’t define political options but political moments. Trump simply took advantage of the moment.

Back to Brazil

The clash between Lula and Bolsonaro is therefore not simply a Brazilian peculiarity. It is contained within a larger logic. One that results from a conjunction of historical factors that go beyond abstract constructs like national boundaries.

It is not our intention, as opposed to cultural variables, to present the international political economy as the “ultimate determinant” of the populist phenomenon, but to understand it as the construction of the political.

Tautologically, it emerges when the conditions for it emerge, that is, it occurs in its moment. This moment, indeed, is constantly found between an “old” and a “new” world orders, that is, between different “historical blocs”.

No doubt an “old” social, political, and economic arrangement has already died in Brazil. The “Jornadas de Junho” in 2013 were a prelude to its deterioration, all the mobilization and all the conspiracies that followed the 2014 elections indicated a worsening of its clinical condition and its death was finally declared by the impeachment in August 2016.

Any deeper analysis to be made of this moment must therefore consider the hegemonic dispute in question. That means it should be taken into account the dialectics “structure” and “superstructure” in the context of a serious economic crisis, as well as the dialectics “political society” and “civil society” in the context of a populist dispute for “empty signifiers”.

In conclusion, some theses can be proposed about the current Brazilian situation. Firstly, the political form based on the polarization PT vs PSDB has reached exhaustion, just as the economic and neo-developmental form ends in the neoliberalism of Michel Temer.

Secondly, Lula’s strength is greater than the strength of his party, and it has to do with his populist political construction, which again finds a favorable moment. Lastly, the emergence of Bolsonaro has little to do with the content of his politics and policies, but only with the populist moment.

Only in the coming months shall we see the development of our crisis, little can be anticipated. Variables that intervene to any predictions may arise from the most diverse possibilities: from a new Lava Jato arrest (and there are those who guarantee that Lula is next in line) to some event that sparks the political violence that lies latent in Brazil.

In any case, politics continues in Brazil as it has never ceased to be: the farce of tragedy and the tragedy of farce

Caio Gontijo is a Master’s student in International Politics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

This article appeared originally in Modern Diplomacy – http://moderndiplomacy.eu/