For long considered a patrimony of Brazilian music, Francisco Buarque de Hollanda, better known as Chico Buarque, has just been chosen Brazil’s Musician of the Century in a competition promoted by weekly news magazine Isto É. Competing with him there were such music legends as Tom Jobim, who came in second, Milton Nascimento, João Gilberto, Noel Rosa, Pixinguinha, Caetano Veloso, and Gilberto Gil. Brazzil tells the story of the genius Chico Buarque.

Since November of last year, Chico Buarque’s name has been in the news quite a bit, after an absence of five years. It started with the launching of his new CD, As Cidades (The Cities) and has continued with the national tour starting in Rio. There had been whispers, some not so softly, that he was washed up. Veja, one of the most widely read magazines in Brazil, carried an article in November of 1998 stating that Chico Buarque was in a creative crisis, and that As Cidades was an inferior CD. The authors blamed it partly on his drinking, partly on the breakup of his marriage of thirty years after some rumored extramarital affairs on his part.

The article was a mean-spirited attempt at trashing one of the great geniuses of Brazilian music—a man chosen as the greatest by the other leading magazine, Isto É, just recently. When this author visited Rio in January, there were no CDs to be had in the stores, and Canecão was sold out with a few standing room tickets left. And when Chico visited Salvador earlier this year for the christening of his grandchildren, Chico and Clara, children of his daughter Helena and musician Carlinhos Brown, Baianos flocked around him as they do to their local heroes, Caetano and Gil. As of March 16th, http://www.musicboulevard.com has As Cidades in their catalog. Log on, get it, listen, and form your own opinion. And now, for the story of Chico, fasten your seatbelts.

On June 19th, 1944 at the maternity ward São Sebastião, Largo do Machado, Rio de Janeiro, Francisco Buarque de Hollanda, Chico, was born the 4th of 7 children of historian and sociologist Sérgio Buarque de Hollanda and pianist Maria Amélia Cesário Alvim. In 1946 the family moved to São Paulo where Sérgio accepted the post of director of the Museu do Ipiranga.

At five, Chico already showed his interest in music with an album of pictures of singers he had heard on the radio. And a year later, as the family was about to make a voyage to Europe, young Chico said to his grandmother, “Grandma, you’re very old, and when I come back, I won’t see you anymore, but I’m gonna be a singer on radio, and you will be able to turn on the radio in Heaven if you miss me.” In 1953, Sérgio was invited to teach at the University of Rome, and the family moved to Italy. It was here that Chico became tri-lingual. He spoke English in the American School, Portuguese at home, and Italian in the streets. It was also here that he composed his first marchinhas de carnaval, little Carnaval marches.

In the house in Rome, the eternally curious Chico would hide at the top of the stairs after having been sent to bed and listen to conversations his parents had with friends, such as the great poet Vinícius de Moraes. Later, the composer Chico Buarque would form a partnership with the poet. About 1956, the family returned to São Paulo. His sister, Ana Maria, Baía, remembers that Chico at the age of 12 or 13 composed some operettas together with sister Miúcha, nicknamed Heloísa. The family moved to a big house in Rua Buri, a couple of blocks from the stadium Pacaembu. Although he was a devoted fan of the Fluminense club of Rio, his idol played for Santos. His name was Paulo César de Araújo, Pagão, a name Chico still uses in homage to the star. Some of his friends joke that Chico Buarque only turned to music because he didn’t shine at soccer.

In school Chico showed great interest in the classic literature of France, Germany, and Russia. His interest in Brazilian literature only started when someone criticized him for not appearing to care about it. His budding interest in Brazilian literature might have gone a little too far when he took a rare first edition of Macunaíma by Mário de Andrade from his father’s book case and paraded around campus with it. That earned him a paternal reprimand.

Youth Follies

In 1958, influenced by a professor, he entered a religious movement called Ultramontanos, a precursor of the ultraconservative organ TFP (Tradição, Família e Propriedade—Tradition, Family and Property). His involvement with the Ultramontanos grew to steady worry for his parents. He even abandoned playing soccer. Concerned, his parents sent him to a boarding school in Cataguases, in the interior of Minas Gerais, for a semester.

Upon returning to São Paulo, he also returned to his involvement in a religious movement, this time one of a social nature called Organização Auxílio Fraterno (Fraternal Aid Organization), which took food and other goods to the homeless. Chico Buarque, who has never been a believer in charity as a solution to social ills, describes this time as “an experience that kept him from becoming alienated.”

It was also during this time that his interest in music flourished. His first love were the traditional sambas of Noel Rosa, Ismael Silva, and Ataulfo Alves. However, he also listened to such varied foreign artists as French Jacques Brel, Elvis Presley, and The Platters. But it was “Chega de Saudade,” Tom Jobim’s song with João Gilberto’s revolutionary beat that turned Chico Buarque’s musical world upside-down. In fact, he drove the neighbors crazy playing the record incessantly. Even his sister, Miúcha, who would later marry João Gilberto, could not put up with it.

His dream at this time was to “sing like João Gilberto, compose like Tom Jobim, and write lyrics like Vinícius de Moraes.” And he followed up his dream by composing his first song, “Canção dos Olhos,” (Song of the Eyes). The sixties expanded his means of expression in that he published his first chronicles in the paper he called Verbâmidas in Colégio Santa Cruz. It became his ambition to one day see his words in print in the weekly magazines side by side with established writers.

He soon did get his wish of appearing in print, but not in the way he had imagined or that would make his parents proud. His photo and that of a friend appeared on the pages of Última Hora (Last Hour), a São Paulo newspaper, eyes covered because of their ages, when they stole a car to do some early morning joyriding _ a favorite pastime of teens then and now. His parents, however, were not amused, and young Chico was grounded at night until he turned 18.

In 1963, Chico Buarque was matriculated at FAU (Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo of the University of São Paulo). But with the military coup in 1964 came repression of all institutions of learning, and after Chico had studied for 3 years, he abandoned his studies and destroyed the dream of his maternal grandmother, Maria do Carmo that her grandson go on to design cities.

Not all the events of 1964, however, were negative. It was also the year in which Chico Buarque first set foot on stage to sing. This happened at Colégio Santa Cruz, and he sang his own “Canção dos Olhos” (Song of the Eyes). The song “Tem Mais Samba” (There is More Samba), made for the musical Balanço de Orfeu, is one that Chico today considers the starting point of his career.

It is also during this time that the groundwork is laid for the craze of the music festivals. The most famous of the shows was the one presented at the Paramount on Avenida Brigadeiro Luís Antônio in São Paulo. At the show O Fino da Bossa under the leadership of Elis Regina, were introduced such luminaries and future stars as Alaíde Costa, Zimbo Trio, Oscar Castro Neves, Jorge Ben, Nara Leão, Sérgio Mendes, and Os Cariocas. At Colégio Santa Cruz, the show Primeira Audição (First Audition), made room for musicians of the new generation. Chico Buarque presented here his new song “Marcha para um Dia de Sol,” (March toward a day of sunshine).

1965 saw his first single “Pedro Pedreiro,” (Pedro the Stonemason) and “Sonho de um Carnaval,” (Dream of a Carnaval), arrive on the market. “Sonho” was the first song entered into a festival at TV Excelsior. The song, sung and subsequently recorded by Geraldo Vandré, did not classify.

Chico also tried his hand at acting and appeared with Eva Wilma and John Herbert on a soap on TV Tupi, Prisioneiro do Sonho (Prisoner of the dream), in which he played “one of those performers of bossa nova.” He wrote the music for the poem “Morte e Vida Severina” by João Cabral de Melo Neto whose production won praise by critics and public in Nancy, France.

It was in 1965, at the João Sebastião Bar, a Paulista stronghold for bossa nova, that Chico met Gilberto Gil for the first time. Later, the same year, he met Caetano Veloso, who was very enthusiastic about hearing Olê, Olá in a show. The basement of the architectural faculty was often the site of parties and musical encounters, and it was here that Chico became familiar with Taiguara and João do Vale, composer of the famous “Carcará.”

Inspired and encouraged by previous successes, TV Record launched the program Fino da Bossa with a special segment called First Audition, which allowed the appearance of new composers. Chico found out what it meant to be a professional musician. He received his first pay, 50,000 cruzeiros, about $30 for his participation in O Momento da Bossa promoted by Walter Silva.

At the second Festival de Música Popular Brasileira, in October of 1966, Chico’s song “A Banda” (The Band), shared first place with “Disparada” (At Full Tilt), by Théo de Barros and Geraldo Vandré. The song was an immediate success that sold over 5,000 records in a week. The poet, Carlos Drummond de Andrade acclaimed the song in a chronicle, and the song was soon translated into several languages. An unusual honor was bestowed on the song in that since 1978, it has been part of the repertoire of the Irish Guards Band, one of the musical bands that play at the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace.

New Image

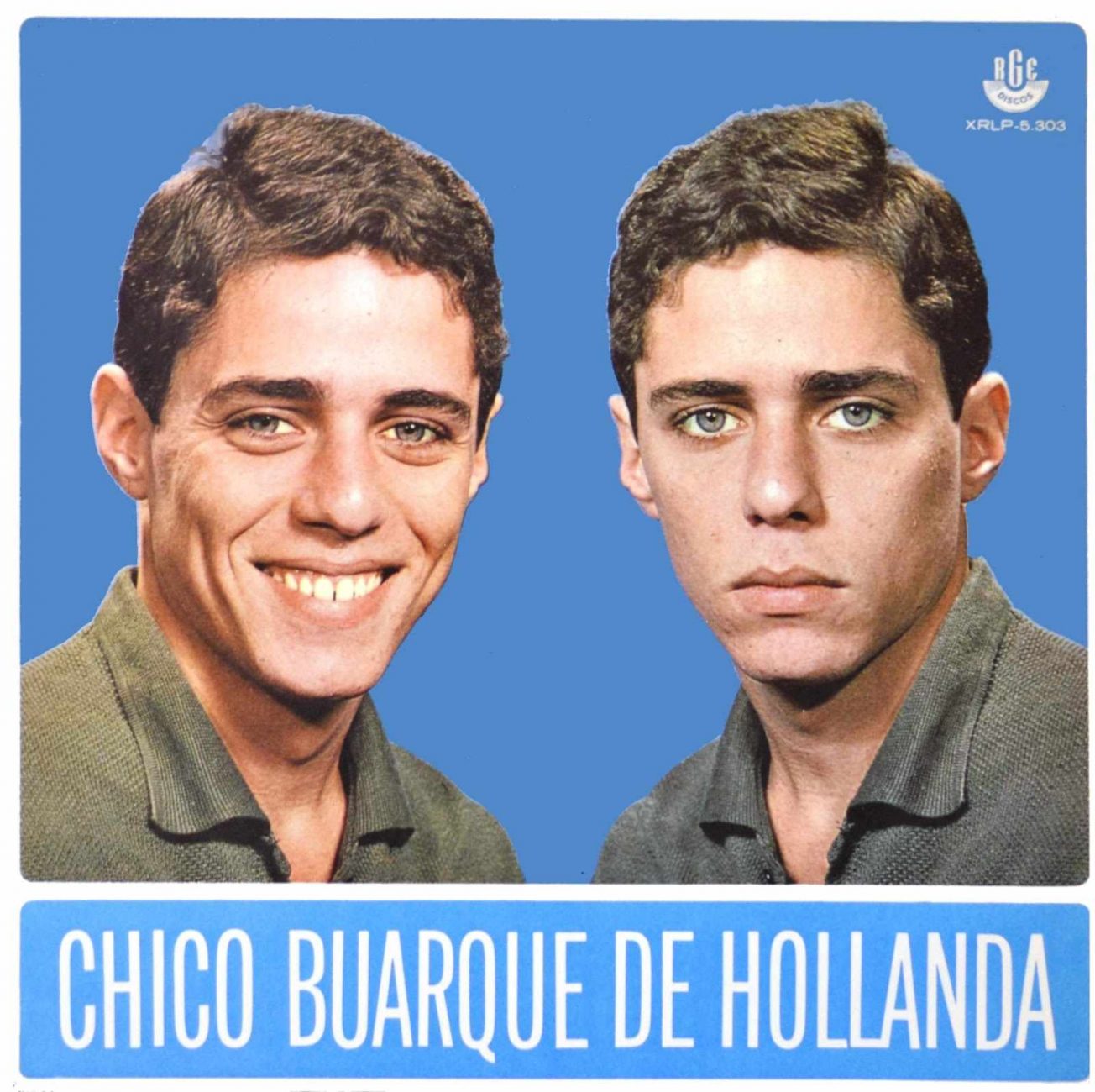

It was about this time that he moved to the city of his birth, Rio de Janeiro, and issued his first LP on RGE, Chico Buarque de Hollanda. Thus occurred also his first run-in with the military dictatorship’s censors. The song “Tamandaré,” which was on the repertoire of the show Meu Refrão (My Refrain), with the group MPB4 and Odette Lara, was prohibited after six months for a few phrases considered offensive to the navy admiral whose face appeared on the old cruzeiro note.

He received a great honor during this time, namely that of being the youngest artist to record an entry for the Museum of Image and Sound—something hitherto reserved for older generations. It was his first foray into writing music for children when he composed the music for the play The Ugly Duckling. Almost simultaneously, he launched his first songbook A Banda with manuscripts of lyrics and the story Ulisses. He then met the actress Marieta Severo, whom he would later marry and with whom he would have three daughters.

At a time when political uncertainty was the only sure thing in Brazil, Chico Buarque became a national symbol of unity, “the man every woman wanted to marry and every man wanted to emulate.” Renowned writer and cartoonist Millôr Fernandes called him “the only national unanimity.” He represented a return to better times before the military regime.

Although living in Rio, Chico continued to appear on and record programs in São Paulo, such as the music program on TV Record Pra Ver a Banda Passar (To See the Band Pass By), with Nara Leão. Plagued by shyness, Chico did not much like television and only felt comfortable about appearing on Esta Noite Se Improvisa (Tonight We Improvise) also on TV Record where he alternated with Caetano Veloso for the first place in knowledge of lyrics of Brazilian songs. He had his debut as a film actor in Leon Hirszman’s Garota de Ipanema (Girl from Ipanema), alongside Tom Jobim, Nara Leão, and Ronnie Von, in which he played himself.

One of Chico Buarque’s most beautiful songs, “Carolina,” took 3rd place in FIC (Festival Internacional da Canção—International Song Festival) promoted by Rede Globo television network, and his “Roda Viva” as well came in 3rd in III Festival da MPB on TV Record. It was a time of transition in MPB. A group of musicians, among them Gilberto Gil, Elis Regina, Jair Rodrigues, and the members of MPB4 organized a protest march against electric guitars in MPB, and although agreeing with them, Chico did not participate. He was in the process of writing the play Roda Viva, but did have time in between to record Chico Buarque de Hollanda vol. 2.

When a student was shot and killed in Rio in 1968, it resulted in a protest march in which Chico participated. Along with his growing popularity among Brazilians, his problems with the government grew. Seeing him as a rebel causing “dangerous” thoughts, the military censors prohibited many of his works—contributing, of course, to their popularity. That was not the case, however, with his play Roda Viva, a satire portraying a popular singer as being devoured by his fans. The military and the people were offended, and on the 18th of July, 1968, members of the CCC (Comando de Caça aos Comunistas—Comando for the Hunt of Communists) invaded a theater in São Paulo and beat up on actors and stage workers.

Meanwhile, Chico continued his victorious ways with “Sabiá”, made in partnership with Tom Jobim, who also composed “Pois É” (That’s Right) and “Retrato em Branco e Preto” (Portrait in White and Black). The press was full of stories of disagreements between Chico Buarque and the Tropicalistas who criticized Chico. Caetano Veloso is quoted as having said, “Chico Buarque continues making that which is pretty, while we’d also like to see things that are ugly.”

Days after the Institutional Act No 5 on December 13th, which strengthened the military government’s grip on the population, he was detained at his house and taken to the military barracks and questioned about his participation in the 100,000 person march as well as the scenes in Roda Viva considered subversive.

Likely because of his family background, he was treated less harshly than other dissidents of the military. Thus, with authorization from a Colonel Átila, whom he had to ask permission to leave town, Chico left Brazil in January and attended a large trade show for the phonographic industry held in Europe. After its conclusion, he went into a self-imposed exile in Italy. His song “A Banda” had been recorded by Italian singer Mina and had landed on the charts, but even so, his next two LPs met with little success in Italy. After some hard financial times, things started looking up with a contract from Phillips for a new LP. His payment for that was about $21,000, enough to sustain the young family which on March 28th was enlarged with Sílvia Severo Buarque de Hollanda, the first of his three daughters, who had as godfather none other than Vinícius de Moraes.

Chico was doing well in Europe, touring and being the opening act for Josephine Baker. He contacted Toquinho and invited him to join him in shows in Italy. Chico Buarque, being a life long lover of soccer, had the great pleasure of spending time with Mané Garrincha, by many considered the greatest soccer player ever. Not only did he enjoy the times they spent together talking about music and soccer, it also earned him great respect in his neighborhood bar in Rome.

From time to time he contributed to the political satirical O Pasquim in Brazil with articles. O Pasquim was, at the time, one of the landmark periodicals of Brazilian journalism. In 1970, Chico Buarque had had enough of exile and returned to Brazil amidst a grand scale welcome at the airport with the attendance of a large crowd of people, press, and cameras—a spectacle arranged on the initiation of Vinícius de Moraes, to show the military how much he was missed in Brazil and demonstrate that they were not to “mess with him.” Scheduled was also a show at the club Sucata to launch his 4th LP—a work of transition, recorded under adverse circumstances. On it he stays away from traditional samba and reveals new influences.

It was not long, however, before Chico was in trouble again with the censors. The single Apesar de Você, (In Spite of You), surprisingly passed the sharp eye of the censors and sold over 100,000 copies. That is when it must have dawned on somebody that the lyrics were highly political. The mighty seemed to have missed what everybody else in Brazil knew without a doubt, namely that the você, you, in the song referred to general Emílio Garrastazu Médici, then president of the republic, in whose government were committed the worst atrocities against the opposition to the regime.

Upon being interrogated, Chico was asked who você was. His response was, “It’s a very authoritarian woman.” After this episode, his songs were always besieged by censors. He participated in the Counsel of Cebrade (Centro Brasil Democrático—Democratic Brazil Center), an organization of intellectuals, publicly against the military, alongside such notables as the architect Oscar Niemeyer, the editor Ênio Silveira, and his own father. His association with the Cebrade earned him, for a while, the label of member of the auxiliary line of one of the two communist parties, the pro Moscow PCB (Partido Comunista Brasileiro—Brazilian Communist Party). Along with the struggle and problems was also good news in the Buarque family. On December 22nd, little Helena was born to the proud parents.

Other

Interests

In 1971, his samba “Bolsa de Amores” (Purse of Love) composed as a play on words on the Bolsa de Valores (the Stock Exchange) for Mário Reis, a trader there. It was immediately banned as “offensive to the women of Brazil.” The new LP came out with one cut less than the usual 12. He had a run-in with TV Globo and cancelled his enrollment in the VI International Festival of Songs in protest against the policy that more famous singers did not have to pass through the eliminating phases.

In 1972, he performed with Caetano Veloso at TCA, Teatro Castro Alves in Salvador—a performance that resulted in the LP Juntos (Together). There always existed a kind of rivalry between the two. Why is anyone’s guess. Perhaps it is that they are both intellectuals who appear to attack their art from diametrically opposed angles. Perhaps, merely “one of those things.” At any rate, when launching his new CD, Livro (Book), which contains the song “Pra Ninguém” (For Nobody)—a kind of answer to Chico’s “Paratodos” (For Everybody), Caetano said, “It seems as if my career has been in pursuit of Chico’s.”

The seventies was a decade of artistic expression going in many different directions for the multi talented Buarque. He launched a double album Ópera do Malandro (Opera of the Crook), he wrote music for film and theater, such as República dos Assasinos (Republic of the Assassins) by Miguel Faria, Jr.; Sob Medida (To Measure); Não Sonho Mais, (I Don’t Dream Anymore); Bye Bye, Brasil by Cacá Diegues for which he wrote the song of the same name, and “Dueto” (Duet) for the play O Rei de Ramos by Dias Gomes. If that weren’t enough, his literary career took off with his first children’s book Chapeuzinho Amarelo (Little Yellow Hat), illustrated by Donatella Berlendis.

After 12 years with PolyGram, Chico left them and signed a recording contract with Ariola. Ironically, PolyGram bought out Ariola the following year. Along with many other artists, he participated in Festa do Avante, the official organ of Partido Comunista Português and Projeto Kulunga in Angola. He was joined by 64 other Brazilian artists at a charity performance for the construction of a hospital.

Argentine filmmaker, Maurício Berú made a documentary about Chico Buarque, Certas Palavras (Certain Words), with participation of Caetano Veloso, Maria Bethânia, and Vinícius de Moraes, who appeared here for the last time. Toquinho, Francis Hime, Ruy Guerra, Miúcha, Sérgio Buarque de Hollanda, as well as other friends and acquaintances.

While this was going on, Chico was busy writing songs for the play O Último dos Nukupirus by Ziraldo Gugu Olimecha and launching a new album Vida (Life), which has, among others, the track Eu Te Amo (I Love You), composed especially for the film of the same name by Arnaldo Jabor.

In 1981, he tried his hand at writing a screenplay with Sérgio Bardotti, Antônio Pedro, and Teresa Trautman for the film Saltimbancos Trapalhões. At the same time, he published a poem which had been put away in a drawer for the past 17 years. It was “A Bordo do Rui Barbosa” (Aboard the Rui Barbosa), written between 63 and 64, with illustrations by his friend Valandro Keating. At the same time, he also issued two new albums, Almanaque and Saltimbancos Trapalhões.

In 1982, in partnership with Edu Lobo, he composed the songs for the ballet O Grande Circo Místico (The Great Mystic Circus), which would be issued on LP the following year. Sadly, during this year, Sérgio Buarque de Hollanda, his father, died at the age of 79.

During 1983/84, Chico worked with filmmaker Miguel Faria, Jr. On the adaptation and screenplay for the film Para Viver um Grande Amor (To Live a Great Love). In 1983, he wrote his classic song Vai Passar (It will Pass), a powerful song, which became a reference for the movement Diretas Já (Popular Vote Now), although Chico denied having written it for that purpose.

The prolific artists composed “Mil Perdões,” (A Thousand Pardons) for the film Perdoa-me por Me Traíres (Pardon Me for Betraying Me) by Braz Chediak. For the play Dr. Getúlio by Dias Gomes and Ferreira Gullar, he composed the song of the same name. Having been away from the stage for nine years, he appeared again at Luna Park in Buenos Aires. During a taping at TV Bandeirantes, he had a surprise encounter with his idol, Pagão, former soccer player with Santos—arranged by director Roberto de Oliveira.

Not satisfied with all his accomplishments, Chico Buarque published, in 1991, his first novel Estorvo (Trouble), which was quickly translated into a variety of languages and published in Europe and the United States. In Portugal, it sold 7,500 copies in just 3 days, to the amazement of the publishing house Dom Quixote. In 1994, after a recording pause of four years, Chico Buarque launched his new CD Paratodos (For Everybody). After much anticipation, he toured with the show to rave reviews.

Always a man of social consciousness, he participated in the Campanha Nacional Contra a Fome e Pela Cidadania (The National Campaign Against Hunger and for Citizenship) initiated by sociologist Herbert de Souza, Betinho. His second novel Benjamim received less favorable reviews in the literary press, in spite of being a success in the bookstores and receiving praise from other writers. Another pause followed the success of Paratodos. A collection of his best songs was issued under the title As Palavras (The Words).

In 1998, Chico Buarque was the subject of the Carnaval theme of the samba school Mangueira, which went on to win the competition. It was a great triumph for Chico Buarque who participated in the parade in Rio. And it was in 1998 that his new CD As Cidades (The Cities) hit the stores. A quiet, contemplative CD, it gets better for every time one hears it.

His Works

Literature

The first songbook, A Banda, Chico Buarque published in 1968 contained lyrics and musical charts, the story “Ulisses,” which he would later call “a little weak,” and a chronicle by Carlos Drummond de Andrade about “A Banda,” which had already been published in the literary section of daily O Estado de S. Paulo.

Chapeuzinho Amarelo (Little Yellow Hat). This book/poem from 1979 is the first publication dedicated to children. A little girl illustrates in a humorous manner, the comings and goings of child like fears. The book was considered highly commendable by the National Foundation of Child and Youth Books in 1979.

Fazenda Modelo—Novela Pecuária (Fazenda Modelo—Cattle-raising Story). “Chico Buarque weaves an allegory of a society of men—speaking, however, exclusively of bulls and cows. It is a parable of power, in respect to forms of social dominance over the human herd. And the more radical domination is to usurp the individual—always in the name of more sacred principles, any possibility of assuming one’s own personal destiny.

The Fazenda Modelo is a bovine community which begins to grow and which is seen—through the calm leadership of the bull Juvenal, the good—subjected to a radical process of transformation of “progress,” in which everything natural is considered backwards or sinful and becomes scientifically regulated.

“All forms of self regulation of the individual are eliminated—from food intake to sexual expression; procreation is guaranteed through artificial insemination from the sperm bank of the bull Abá, the Great Reproducer. Juvenal abolishes sexual relations of the herd. And the son of Abá, Lubino, is supposed to succeed his father in the glorious role at Fazenda Modelo. It is exactly at the moment of “initiation” of Lubino by Juvenal that the chosen path will present itself.” Adélia Bezerra de Menezes, Literatura Comentada, 1980.

A Bordo do Rui Barbosa (Aboard the Rui Barbosa). “The poem is from 63 or 64. Years during which we dedicated ourselves to not study architecture. We made bossa nova in the basements of the FAU, Vallandro on guitar and I with lyrics. 15 years later, Vallandro appears before me with this poem all crumpled up. It took me a while to recognize it. After he showed me his idea of the designs, I found it beautiful. It was like he had put music to my lyrics.” Chico Buarque, Rio, 1981

Estorvo (Trouble). “This novel by Chico Buarque, at the first reading, affirms itself as an exemplary demonstration of a novel. Estorvo, is as far as I’m concerned, a hallucinated pilgrimage in search of lost roots, through an existential journey populated with amazement and solitude. Here, all the functions of the equilibrium of social structures—family, friendship, power—lose their formal consistency from the first clash and ruptures when the glance of the protagonist (and the writer) extends over them.” José Cardoso Pires, Folha de São Paulo, 1994.

Benjamim. “It is a story of blame, bitter, dense, almost suffocating. Narrated in third person, it permits the narrator to know the facts and points of view of the other characters. The word is the basic character of Chico’s new novel, as in his last CD, Uma Palavra, also issued this year. Benjamim, by definition is the favorite son. Benjamim Zambraia, the protagonist, is not, nor will he be the favorite of anyone. He is in front of the firing squad from the first sentence of the book. When he hears the shots, his existence—the time is another character—projects itself, as he already expected, “from the beginning to the end, just like a film.”” Jornal da Tarde, 1995

Theater

Roda Viva. The play, which was written as a satire, is about a popular singer who feels used and “devoured” by his audience. At the performance, actors offered pieces of his “liver” to the audience. At a performance of the play in July, 1968 in São Paulo at the Teatro Galpão, some 100 members of the CCC (Comando de Caça aos Comunistas—Comando for the Hunt of Communists), invaded the show and beat up on actors and stage hands. The following day, Chico was in the audience to support the group and began a movement organized in defense of Roda Viva and against censorship on the Brazilian stages.

Calabar. Calabar was written at the end of 1973, in partnership with filmmaker Ruy Guerra and directed by Fernando Peixoto. The play depicts the position of Domingos Fernandes Calabar during the historic episode in which he chose to take sides with the Dutch against the Portuguese crown. It was one of the most expensive theatrical productions of the time, costing about $30,000 and employed more than 80 people. As always, the censors of the military regime had to approve and release the work at a rehearsal dedicated to that purpose. After the show was ready, there was a wait for the final approval. That took 3 months, and in October 1974, General Antônio Bandeira of the Federal Police, without apparent motive, prohibited the play, prohibited the name Calabar, and if that weren’t enough, even prohibited that the prohibition be divulged. The damage to the authors, actor Fernando Torres, producers of the play, was enormous. Six years later, a new production had its début, this time released by the censors.

Gota D’água (Last Straw). In 1975, Chico wrote with Paulo Pontes, the play Gota D’água, inspired by a project of Oduvaldo Viana Filho, who had already done an adaptation of Medea by Euripides, for television. The urban tragedy, in the form of a poem with more that 4,000 verses, has as its backdrop the bitterness suffered by the inhabitants of a joint community, the Vila do Meio-Dia, and, in the center the relationship between Joana and Jasão, a popular composer under the influence of the powerful manager Creonte. Jasão ends up leaving Joana and the two children to marry Alma, daughter of the manager. The first showing had Bibi Ferreira in the role of Joana and was under direction of Gianni Ratto.

Ópera do Malandro (Opera of the Crook). “The text is based on the Beggar’s Opera of 1728 by John Gay and The Threepenny Opera by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill. The work originates in an analysis of those two plays by Luís Antônio Martinez Corrêa and counted on the collaboration of Maurício Sette, Marieta Severo, Rita Murtinho, and Carlos Gregório. The team also cooperated in the realization of the final text through readings and suggestions. During this stage of the work, we benefited a great deal from the films Threepenny Opera, by Pabst, and Getúlio Vargas by Ana Carolina, the studies of Bernard Dort O Teatro e Sua Realidade (The Theater and its Reality), the memoirs of Madame Satan, as well as the friendship and testimony of Grande Otelo.

“We also relied on Professor Manuel Maurício de Albuquerque for a better perception of the different historic moments through which the three operas passed. Professor Luiz Werneck Vianna contributed, later, with very informative observations. And Maurício Arraes got together with our group in the phase of transposition from text to the stage.

We are grateful to Dr. João Carlos Muller for the commitment with which he fought with the Federal censors for the release of the play, in the courts. In the same sentiment we are grateful to Messrs. Luís Macedo and Humberto Barreto. Finally, a hug for the cast who understood our creative process and became part of it. This play is dedicated to the memory of Paulo Pontes.” Chico Buarque, Rio de Janeiro, June 1978.

Julinho de

Adelaide

One cannot mention the works of Chico Buarque without talking about Julinho de Adelaide. At the height of the military rule, when the censors mercilessly prohibited everything Chico Buarque touched, a new star appeared to hit the market, Julinho de Adelaide. Chico would record the songs of this new artist whose songs were so lyrical and not dissimilar to his own. Songs like “Acorda Amor” (Wake up, Love), “Jorge Maravilha” (Jorge Marvel), “Milagre Brasileiro” (Brazilian Miracle) passed through the censors without major problems, until at one point it became known that Julinho de Adelaide and Chico Buarque were one and the same. After that, a copy of a person’s identification papers was required when a text was submitted for the censors.

Kirsten Weinoldt was born in Denmark and came to the U.S. in 1969. She fell in love with Brazil after seeing Black Orpheus many years ago and has lived immersed in Brazilian culture ever since. E-mail: kwracing@erols.com

THE SONGS

Samba do Grande Amor, 1983 Chico BuarqueTinha cá pra mim Que agora sim Eu vivia enfim o grande amor Mentira Me atirei assim De trampolim Fui até o fim um amador Passava um verão A água e pão Dava o meu quinhão pro grande amor Mentira Eu botava a mão No fogo então Com meu coração de fiador Hoje eu tenho apenas uma pedra no meu peito Exijo respeito, não sou mais um sonhador Chego a mudar de calçada Quando aparece uma flor E dou risada do grande amor Mentira Fui muito fiel Comprei anel Botei no papel o grande amor Mentira Reservei hotel Sarapatel E lua-de-mel em Salvador Fui rezar na Sé Pra São José Que eu levava fé no grande amor Mentira Fiz promesssa até Pra Oxumaré De subir a pé o Redentor |

Samba of a Great LoveI had it here for me That now, yes I was finally living my great love A lie I threw myself this way From a diving board I went until the end as an amateur I spent a summer On water and bread I gave my quota to the great love A lie I put my hand In the fire then With my trusting heart Today, I have just a stone in my chest I demand respect, I’m no longer a dreamer I even cross to the other sidewalk When a flower appears I laugh at the great love A lie I was very faithful I bought a ring I put on paper a great love A lie I reserved a hotel room Sarapatel And a honeymoon in Salvador I went to pray at the Sé To São José Since I had faith in the great love A lie I even promised Oxumaré To climb the Redeemer on foot. |

Choro Bandido

Edu Lobo/ Chico Buarque Mesmo que você feche os ouvidos |

Bandit Choro* Even if the singers are false like me They will be beautiful, it doesn’t matter When the songs are beautiful Even if the poets are miserable Their verses are good Even because the notes were muffled When a god sly and crooked Made from the guts the first lyre Which animated all the sounds And from there were born the ballads And the ecstasy of the bandits Just like I am singing: You were born for me You were born for me Even if you stop listening * choro is a type of music, possibly |

A Ostra e o Vento from the new CD As Cidades, 1998 Chico BuarqueVai a onda Nem um barco Se o mar tem o coral |

The Oyster and the Wind The wave goes The cloud comes The leaf falls Who whispers my name? The day shines There is drizzle The father scolds Did my love bring a scent? My secret friend Set my heart fluttering Father, the time is turning Father, let me breathe the wind Wind Neither a boat If the sea has the coral |

A Banda, 1966

Chico BuarqueEstava à toa na vida A minha gente sofrida O homem sério que contava O velho fraco se esqueceu do Mas para meu desencanto E cada qual no seu canto |

The BandI was without reason in my life My love called me To see the band pass by Singing things of love My suffering people The serious man counting The old, weak man forgot But to my disenchantment And everyone in his corner |

| A Mais Bonita, 1989

Chico Buarque Bonita |

The Most Beautiful

No, solitude, today I don’t want Beautiful |

Anos Dourados, 1986 Tom Jobim/Chico BuarqueParece que dizes Não sei se eu ainda |

Golden YearsIt seems that you say I love you Maria In the photo We are happy I call you, nervous And leave confessions On the recorder It will be funny If you have a new love I see myself at your side Do I love you? I don’t remember It seems like December Of a golden year It seems like bolero I want, I want To tell you that I don’t want Your kisses ever again Your kisses ever again I don’t know if yet |

Caçada, 1972Não conheço seu nome ou paradeiro Adivinho seu rastro e cheiro Vou armado de dentes e coragem Vou morder sua carne selvagem Varo a noite sem cochilar, aflito Amanheço imitando o seu grito Me aproximo rondando a sua toca E ao me ver você me provoca Você canta a sua agonia louca Água me borbulha na boca Minha presa rugindo sua raça Pernas se debatendo e o seu fervor Hoje é o dia de graça Hoje é o dia da caça e do caçador Eu me espicho no espaço De tocaia fico e espreitar a fera |

Hunting TripI don’t know your name or whereabouts I guess your trail and smell I set out armed with teeth and courage I’m going to bite your savage flesh I cross the night restless and troubled And wake up imitating your cry I get closer to your burrow And when you see me you taunt me You sing your crazy pain Water bubbles in my mouth My prisoner bellowing her race Legs debating each other and her fervor Today is the day of grace Today is the day of the hunt and the hunter I stretch out in space From an ambush I spy on the beast |

Morena dos Olhos D’água, 1966 Chico BuarqueMorena dos olhos d’água Descansa em meu pobre peito Morena dos olhos d’água, etc. O seu homem foi-se embora Morena dos olhos d’água, etc. |

Morena with Eyes like Water(Morena: Dark Woman) Morena with eyes like water Rest on my poor breast Refrain Your man went away Refrain |