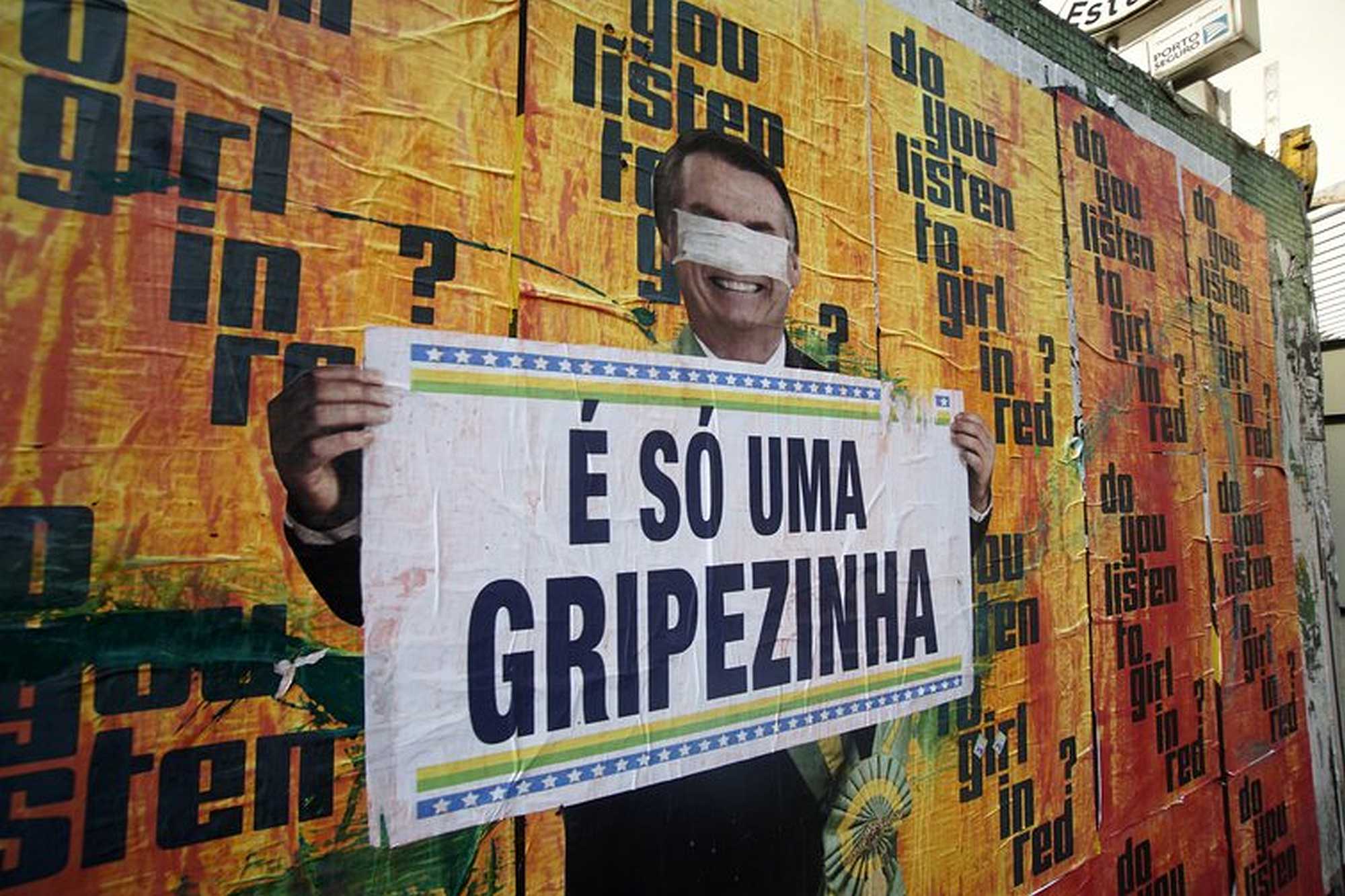

Throughout the pandemic, Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, downplayed the threat posed by Covid-19. In March 2020, he publicly stated that the virus’s effects were like that of “a minor cold” and asserted that he was not concerned about contracting it because of his “athletic physique”.

A month later, Bolsonaro callously brushed off criticism from the press about Brazil’s spike in coronavirus deaths, answering: “So what’? My name is Messiah [a reference to his middle name], but I cannot work miracles.”

In the same month, April 2020, Brazil’s foreign affairs minister, Ernesto Araújo, published an article in Metapolitica, an anti-globalization blog, titled “Here comes the communist virus”.

In it, he declared that “the coronavirus wakes us up again to the communist nightmare”, adding that, “the virus appears, in fact, as an immense opportunity to accelerate the globalist project.

“It was already being carried out through climaticism or climatic alarmism, gender ideology, politically correct dogmatism, immigration, racialism or reorganization of society by principle of race, antinationalism, scientism.”

By giving the pandemic an ideological spin, the Bolsonaro administration compromised Brazil’s response to the crisis. With more than 230,000 Covid-19-related deaths, Brazil has the world’s second highest toll, behind only the US.

Such crises breed sinister opportunities, and Brazil’s has created a political environment of chaos, allowing Bolsonaro’s authoritarian project to thrive. With the nation’s Covid cases seemingly still rising, could impeachment efforts finally be successful?

Military Threat

Amid an unprecedented public health crisis, Bolsonaro has shown an increasingly authoritarian attitude. At the onset of the pandemic, Bolsonaro sacked Brazil’s health minister, Luiz Henrique Mandetta, who had been strictly following the World Health Organization guidelines for managing the pandemic. A week later, the Brazilian justice minister, Sergio Moro, resigned, creating an unprecedented political and constitutional crisis.

Moro rose to prominence for leading the mega anti-corruption initiative Operation Car Wash (Operação Lava-Jato), which resulted in the arrest of several politicians, including the former president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Worker’s Party.

Moro’s resignation was explosive: he accused Bolsonaro of meddling in Brazil’s Federal Police by appointing Alexandre Ramagem, previously the head of Brazil’s intelligence agency, as the new federal police director.

Ramagem had close ties with the Bolsonaro family. High Court judge Alexandre de Moraes vetoed his appointment, deeming it unconstitutional. Bolsonaro regarded Brazil’s Justice Moraes’s decision “as an interference” and urged his supporters to protest against Brazil’s Supreme Court and Congress.

In response to the High Court’s decision, Bolsonaro’s supporters organized a series of anti-democracy protests. After joining protesters in Brazil’s capital, Brasília, Bolsonaro gave a speech in which he stated: “I am the constitution”.

Throughout April and May, Bolsonaro’s supporters took to the streets of Brazilian cities to demonstrate their support for the administration, calling for the military to step in, as well as for the shutting down of Brazil’s High Court and Congress.

During the 2020 anti-democracy protests, Bolsonaro not only incited his base to subvert the constitutional stay-at-home order, but hinted at a possible military intervention. Many protests turned violent, with reports of journalists being physically attacked.

Bolsonaro’s increasing radicalization was coupled with assaults on Brazil’s free press, with him verbally attacking journalists during a press conference, yelling at them to “shut up”.

Brazil’s political temperature soared last May, following a Supreme Court request to access Bolsonaro’s mobile phone as part of a corruption investigation.

Bolsonaro defied court orders by refusing to surrender his phone and threatened to send the military to the streets and “interfere directly” by shutting down the Supreme Court and Congress. Defense minister Augusto Heleno, however, contended “it is not the time for that”.

Anti-democracy protests have cooled off since. In subsequent statements, however, Bolsonaro expressed his view that the military is above Brazil’s constitution, making assurances that the military will not follow “absurd orders” and that he will not accept “attempts to seize power by another power of the Republic, contrary to the laws, or on account of political judgements”. These are matters of growing concern for the survival of the constitutional order in Brazil.

Within a month, as the pandemic ran out of control, Bolsonaro presided over administrative chaos with the resignation of Moro, ongoing anti-democracy protests, – and the sacking of yet another health minister, Dr Nelson Teich, also over diverging views on social distancing measures and the use of the anti-malarial drug hydroxychloroquine for patients with coronavirus.

(There is no medical evidence that the drug can prevent infections or heal coronavirus patients.) Teich’s questionable replacement, Eduardo Pazuello, is a former army general with no medical training, indicating an increasing militarization of Bolsonaro’s cabinet.

Bolsonaro’s attacks on Brazil’s free press, including personal attacks on journalists, are a matter of constant concern. This year, Bolsonaro live-streamed a video, with the foreign affairs minister and other advisors by his side, in which he cast aspersions on William Bonner, the anchor of Brazil’s most popular daily news broadcast, ‘Jornal Nacional’.

Bonner had aired reports criticizing the Bolsonaro administration’s foreign policy, arguing that it has had a negative impact on Brazil-India relations and Brazil-China relations – which are regarded as crucial for the country’s coronavirus vaccination strategy.

Does Impeachment Beckon?

Between April 2019 and June 2020, Bolsonaro’s approval ratings remained stable, at 30%. According to Statista numbers, however, the president’s popularity soared in August 2020, even after downplaying the pandemic and his constant attacks on Brazil’s democratic institutions and the free press.

Curiously, the majority of Brazilians believe Bolsonaro and his administration are not responsible for the coronavirus crisis, or for Brazil’s high rate of coronavirus-related deaths.

Some analysts argue that the coronavirus emergency stipend bolstered Bolsonaro’s popularity levels, but the president’s increased popularity between August and December 2020 signals an erosion of democracy, raising fears for Brazil’s democratic future.

There have been 69 requests for the impeachment of the president. So far, five have been filed or disregarded, while 64 await review. Despite Brazil’s accelerating pandemic, delays in the country’s national coronavirus immunization roll out, and the collapse of the health system in the city of Manaus, where hospitals have run out of oxygen, Bolsonaro’s approval rate of 30% remains untouched.

The remaining question is whether the impeachment requests will be considered impartially. Bolsonaro recently struck a deal with Brazil’s centrão, a well-known coalition of center-right and right-wing parties that aims for political leverage within the government.

With the support of the centrão, Bolsonaro had Arthur Lira elected as the president of the House of Representatives and Rodrigo Pacheco as the president of the Senate, both of whom support the president’s political agenda, earlier this month.

Although Bolsonaro might now be hostage to the centrão’s political ambitions, this latest move can be seen as checkmate for his opponents.

With Bolsonaro’s growing political influence in both chambers of Congress, it will be increasingly difficult for Brazil’s legislative branch to exercise checks over his authoritarian project, and to hold him accountable.

Flavia Bellieni Zimmermann is a Brazilian-born International Relations Analyst. She is a Teaching Fellow and a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Western Australia School of Social Science, Political Science and International Relations.

This article appeared originally in Open Democracy – https://www.opendemocracy.net/