The bones of Josef Mengele, the infamous German doctor who conducted experiments on prisoners at the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II to the point of becoming known as “Angel Of Death,” are now at the service of Brazilian medical students.

Mengele drowned off the coast of the state of São Paulo, after over four decades on the run. After the war, as leading members of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich were put on trial for war crimes, Mengele fled to Argentina and lived in Buenos Aires for a decade.

He later moved to Paraguay as Israeli Mossad agents were closing in on Nazi fugitives. In 1960, he arrived in São Paulo, where he received shelter from German couple Wolfram and Lisolette Bossert and a family of Hungarian immigrants. Also in 1960, Holocaust mastermind Adolf Eichmann was captured by an Israeli group and flown to Jerusalem for trial.

In 1979, Mengele, then 67, died while swimming in a beach in the coastal town of Bertioga. The Bosserts buried him in Embu on the outskirts of São Paulo city, under the name of Wolfgang Gerhard.

Years later, German authorities intercepted a letter sent by the couple to Mengele’s family with news of his death. They alerted Brazilian authorities.

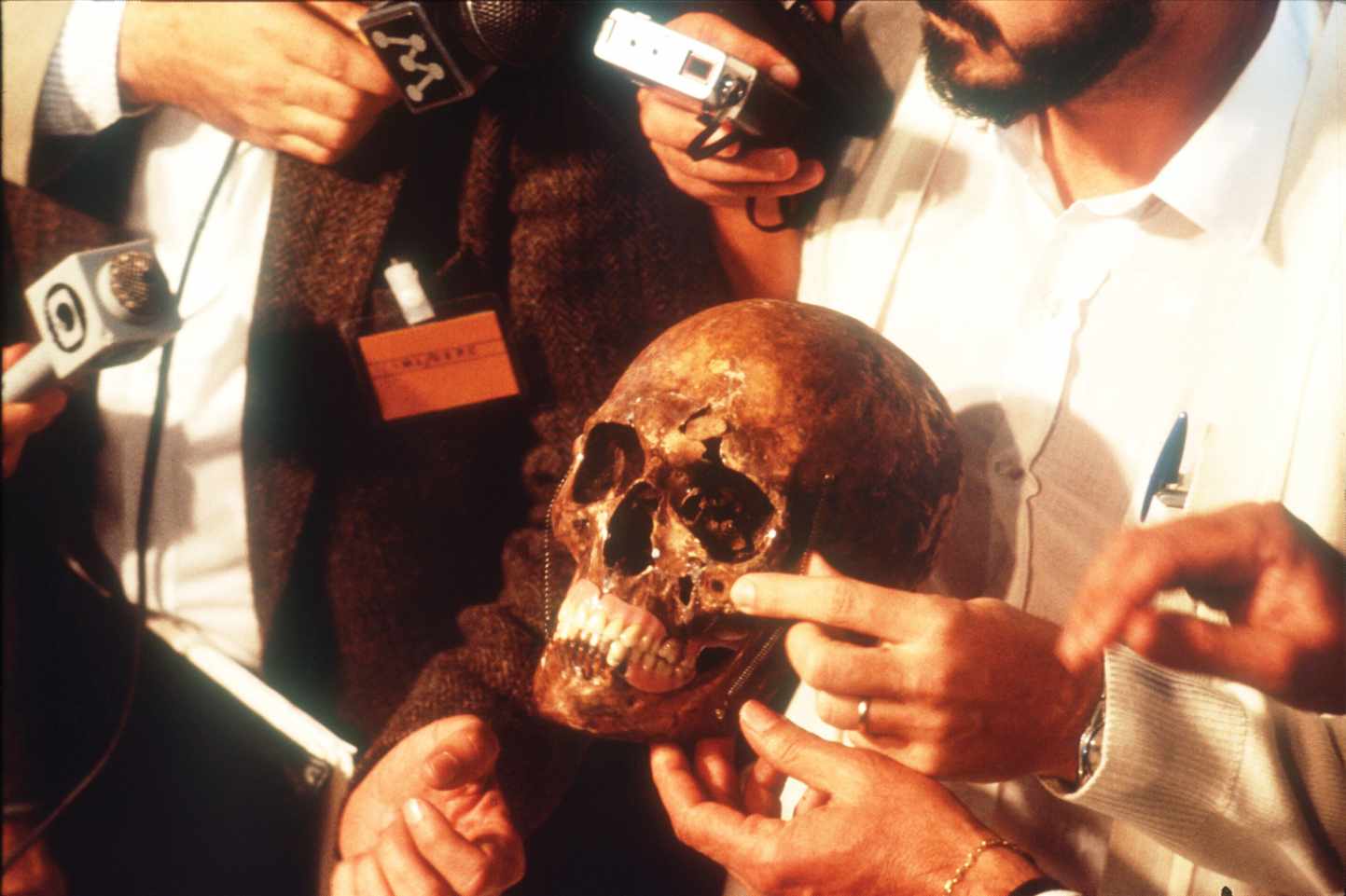

In 1985, his body was exhumed. Teams from Germany, Israel, the United States and Brazil confirmed it was Mengele, using methods including the vetting of personal accounts from people who knew him in Brazil, comparing handwriting in seized letters and analyzing the recovered cranium to see if it matched old photos of Mengele.

Among those experts who identified the remains as Mengele’s was Doctor Daniel Romero Muñoz, who heads the Department of Legal Medicine at the University of Sao Paulo’s Medical School. He has finally obtained permission to use them in his forensic medical courses.

His students are now learning their trade studying Mengele’s bones and connecting them to the Angel of Death’s life story. “The bones will be helpful to teach how to examine the remains of an individual and then match that information with data in documents related to the person,” Muñoz said recently, flanked by students.

Mengele’s life on the run, and the mystery surrounding his whereabouts, are part of what make his bones a useful teaching tool, Muñoz said. “For example, examining Mengele’s remains, we saw a fractured left pelvis,” he said, adding that “information found in his army record said that he fractured his pelvis in a motorcycle accident in Auschwitz,” the notorious Nazi death camp in Poland.

Holding Mengele’s skull, Muñoz pointed to a small hole in the left cheek bone, which he said was the result of long-term sinusitis. Muñoz said that a German couple who harbored Mengele in Brazil told police that he often suffered from dental abscesses that he himself would treat with a razor blade.

“I don’t know what I feel” about Mengele’s bones being studied, said Cyrla Gewertz, a 92-year-old Holocaust survivor. “I already have too many painful memories of him and what he did to me and others at Auschwitz. These are memories I cannot erase from my mind.”

After the war, Gewertz, went to Sweden, where she lived for seven years and where she met and married her husband with whom she came to Brazil in 1952. Originally from Poland, Gewertz has a tattoo on her left arm identifying her as an Auschwitz prisoner: A24840. She said she came face to face with Mengele on several occasions.

“Mengele told me to strip and step inside a large vat with extremely hot water,” said Gewertz during an interview in her São Paulo apartment. “I said the water was too hot and he said if I didn’t do what he ordered, he would kill me. After that I had to step into a vat with freezing water.”

Gewertz said she once saw Mengele kill a newborn baby girl by throwing her off the roof of the camp’s barracks. “He was an evil, perverse man,” she said “He was a torturer.”

Professor Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro, a historian who coordinates the University of Sao Paulo’s Laboratory for the Study of Ethnicity, Racism and Discrimination, said she hopes the classroom learning eventually goes beyond the science to history and ethics.

Students should also learn “how physicians, psychiatrists and other leading scientists were in the service of the Reich, lending their knowledge to exclude the ethnic groups classified as belonging to inferior races,” said Carneiro. “An exclusion that culminated in genocide.”

Mercopress