“Name at least one way to tame the upsurges of tiresome suns, though the uncontrollable in me is the same – endless flows of answers fleeting fiercely, stuck in this stuck pond of the mind. Cathedrals and skyscrapers in sight, towering high up where I am supposed to belong, still so low, still a crow, croaking the never-ending cycle of life, which I observantly go past and beyond, shedding my blood for marble and gold, till the process is complete, and I am loaded to the database of essence”.

“Man of The Future”, in A Lingua do Pulsar

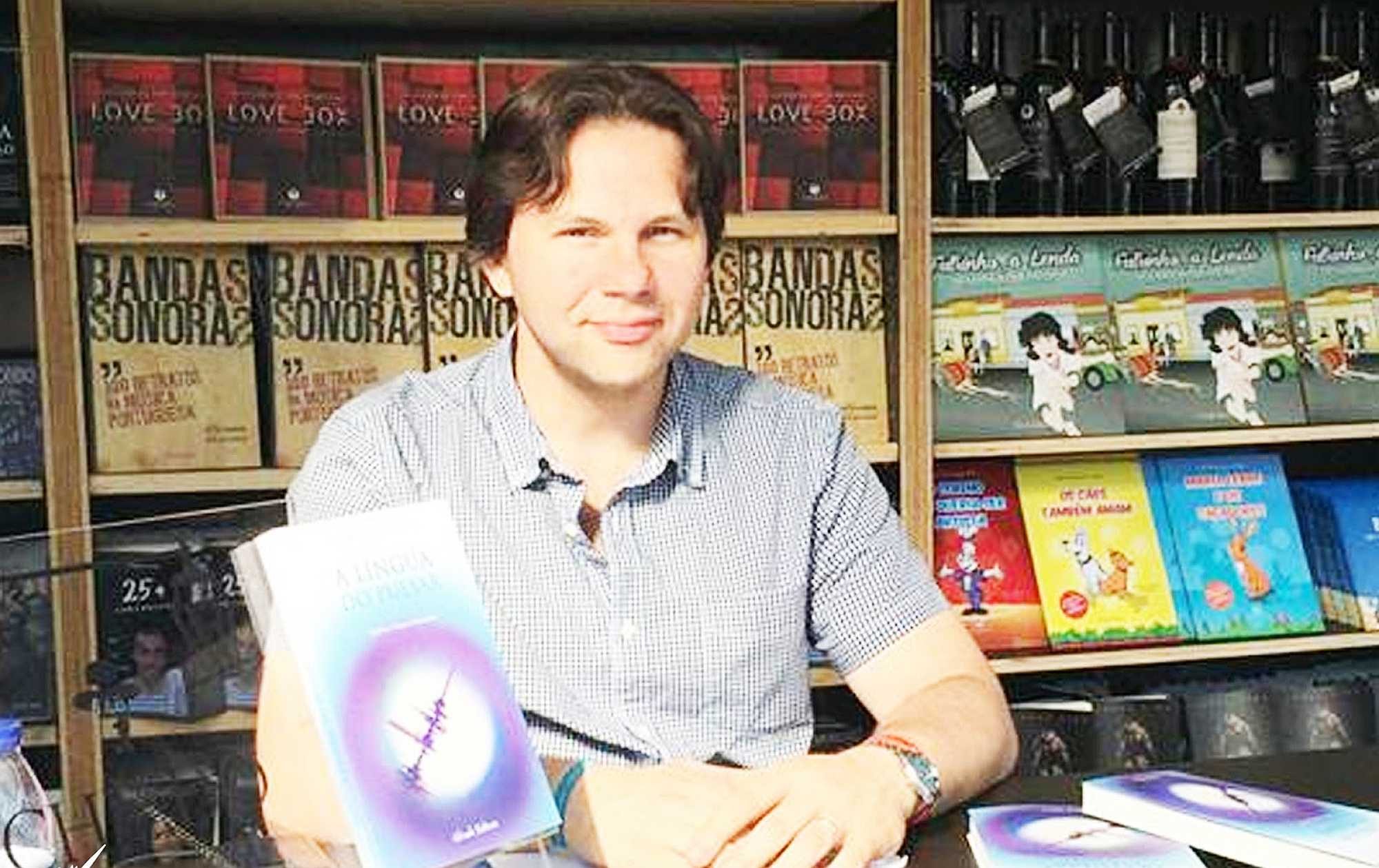

Leonardo Lopes da Silva was born in the Rio de Janeiro suburb of Campo Grande, Brazil, where he lived until he was 28 years old. Brazilian by birth, teacher by trade, writer by impulse.

A wandering man of letters, familiar with being a stranger on strange lands, Leonardo writes in bursts of inspiration, drinking in from Brazilian, Portuguese, American, British, French, Spanish and Russian influences, himself of Portuguese, Native Brazilian, African, and Dutch ancestry, taking residence in cities as diverse as Rio de Janeiro, London and Moscow, where he was based for several years, and currently, in Lisbon.

Manuel Serrano: Leonardo, you have lived in very different countries, amongst different peoples and within contrasting cultures. What have you learned from such experiences and how have they changed the way you understand the world?

Leonardo Lopes da Silva: One of the main eye-opening realizations that I had was when I walked the streets of London by myself as a teenager in 1997, and it was this funny feeling that I had been there before, that every person I walked past shares the same little joys and struggles that I and my fellow countrymen back home did, that we were not that different after all.

I grew up in a world where everything was clearly delineated, North and South, East and West, the rich and the poor, developed and underdeveloped countries (the term “developing” was not yet common at the time).

Living in London has shown me that there are no such absolutes, and that the lines were becoming blurrier and blurrier all the time. You can be a citizen of a multi-cultural, multi-national patchwork of a city which encourages individual freedom, respect and tolerance of different cultures and traditions, but which still put up invisible borders for some urban areas according to the ethnicity or social class of those who lived there, and unwritten rules for relationships and mobility

(“Why on earth would you go shopping in Kilburn? Don’t you know who lives there?”, I was once asked. Or “I would not walk around Brixton at this time of night if I were you”). And that is the London I grew to love deeply, the place where I would be so impressed to see two orange and blue haired punk rockers sucking each other’s faces on the Tube, between an elderly lady with her face buried in a book and a Sikh man fingering his beads.

In this regard, I understood that Rio de Janeiro, my hometown, could be seen as a more egalitarian city, with its geography (poor communities huddled together with upper-class high rise buildings by mountains and seaside locations) and beaches as places where people of all kinds and walks of life come together.

That understanding has changed, however. It all comes down to places of congregation, which are offered by every city, and temporarily lift the tensions and differences between all members of society. London has pubs, parks and the Tube. Rio has its beaches.

Moscow has the 9 May parades and processions. So, going back to my main realization, we are all the same, but we express ourselves in a different way, with varying degrees of introversion or extroversion, in different settings, trying to fool ourselves into thinking that we are doing something unique, with our own language.

Strangely enough though, we are always trying to compare ourselves to others, seeing them as either superior or inferior, more Christian or less Christian, more Muslim or less Muslim, more civilized or less civilized, more authentic or less authentic. Our cultural upbringing is our blessing and our curse.

MS: Brazil, your country of birth, is going through an endless crisis, as corruption and polarization have become common. Meanwhile, in Russia, freedom of expression and political participation is often curtailed by the regime. What can you tell us about these two, very different, crisis?

LLS: They are not as different as you might think. Both crises are features of a trend towards stasis in the democratic scene. The majority of Russians, with some very notable exceptions, have become rather jaded with regards to how much they could achieve by voting, as the result is always the same.

The regime works relentlessly to deprive them of viable options, and there is a growing risk that their machine might have become too efficient at that. It is an environment that is wary of sudden changes, and where the unpalatable items in their agenda – suppression of the rights of “undesirables, almost full control of the media by the government, the pursuing of an untenable economic policy based almost on oil and gas – is offset by the distribution of benefits to the elderly in an ageing population, and the constant expansion of facilities and services in a few privileged cities (Moscow, St. Petersburg, Sochi, key towns in Siberia) at the expense of the impoverishment of the country.

It is important to note, though, that none of that is new. It has, in a way, always happened, since Czarist times, and will keep on happening, in the minds of many Russians. What is familiar and known is always better than the unplanned and the unknown, and they had a very painful lesson with unchecked “democracy” and “capitalism” under the rule of Boris Yeltsin, which led millions to poverty and economic instability. Stability seems to be at the top of the Russian mindset, and it should be pursued at all costs. Vladimir Putin was the answer to their prayers.

What is happening in Brazil is a process of awakening but also quick jadedness. Many Brazilians who came out of poverty joined the middle classes in protesting for changes, but are beginning to realize that the political system has been “rigged”, to use a Trumpism, against them for a long time, maybe since its very beginning.

There is the dismal disillusionment about the value of taking part in politics, as they are under the impression that every single politician is corrupt, at least the ones they do not support.

Ricardo Boechat, one of the most popular newsreaders in Brazilian media, calls this process the footballization of politics – people start consuming political news like sports and taking political sides on social media is a kind of a national pastime, with truculent and foul-mouthed “debates” about which side is better, as if they were supporting their local football team.

We’ve got the “bolsomitos” (supporters of far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro), the “petralhas” (supporters of the Worker’s Party – PT), the “coxinhas” (anyone who opposed the Worker’s Party government initiatives and supported Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment), and this sort of hysteria is making so much noise that it is turning people off political engagement, as well as the growing perception that there are no alternatives left, which gives rise to dangerous precedents in Brazil, such as movements calling for the return of the military dictatorship in Brazil, and historical revisionism – they (the generals who ran Brazil from 1964 to 1985) were not so bad after all, were they?

At least, they were not as corrupt, were they? We had a great deal of economic development, didn’t we? Education in our schools was better, wasn’t it? – these arguable points are being used to slowly gnaw at and undermine Brazilians’ belief in their democratic institutions. That is the most worrisome and terrifying sign, as Brazilian population in 1964 was also divided, and the military solution was offered to them as a way of making life less political, or even apolitical.

It was the aspiration of the military – to remove politics from the equation, and make everything more predictable, more rational, easier to plan. Men will be men, women will be women. Rich will be rich, poor will be poor. The same familiar faces will be on TV and the news, and the scum will be swept under the carpet, or locked up underground.

The yearning for something safe. Something stable. Perhaps it rings a bell?

MS: Leonardo, what would you say that led you to become a writer? It was your family, living in a city like Rio, a very united community? When – and how – did you find your voice?

LLS: I would say that reading so much compelled me to write. My mum encouraged me to read when I was really young, and I haven’t stopped ever since. But I did not write until I was asked by a dear teacher of mine (thank you, Monica Janara) to submit a poem to a school creative writing contest, which I won in my category.

I found it, and still find the poem very mundane and ordinary (it’s got the less than remarkable title “Under the Starry Night”), and have tried to come up with original ways of saying the same things ever since. I used elements of my life in Rio to forge the poetic settings, but they were not always the primary drivers.

I found my poetic voice at an early age, when I tried to put my feelings for girls on paper, and have been verborrhegic, restrained, revolted, meditative, spiritual, passionate, surreal. I wrote my poems inspired by muses, poetic parents and writers I read compulsively, burning images in my mind.

I believe that writing is an enlightening, experimental – shall I say masturbatory? – experience whereby the writer rubs himself against reality and the dictatorial forces of the senses to try and impose his own view of the world, drown, overwhelm the reader with a raw, resounding truth only he and the reader could experience.

I apologize for the image, but I find it hard to avoid using it. Once I started writing, I developed a certain form of blindness and disregard for other contemporary writers’ work, an involuntary misreading of their work, and cultivated a quasi-religious relationship with dead poets and writers. I became a kind of virulent sectarian for my writings, overprotective of them to the point of not even sharing them with anyone but a select few.

Fortunately, with age came the maturity to let go and share them with the world. Writing feels like the ultimate act of self love to me sometimes. You stubbornly keep churning out page upon page of your own views, your own images and words and metaphors, so you will not be silenced by others’.

It is a strange form of egotism to me. Obviously, it is my personal impression, and it is definitely not shared by everyone. I write out of desperation, out of the feeling that I can not hold it in any longer, and this urgency results in something sloppy but spontaneous, cryptic but mesmerizing, dense but true (to my internal reality).

I find myself puzzled when I read my own poems, and they feel as though they did not come from me, but from someone else, with a somber, utterly confident, ultra-masculine (in the sense that it is out to conquer and dominate) voice.

I cannot read any of my poems in their entirety by heart, and that is a sign of the estranged relationship I have with my own voice. I wish to get people to tell me their own impressions about my poems by publishing them in print and online.

MS: And, have you found your audience?

LLS: I have had family and friends and acquaintances who became more than family to me by reading my poems and purchasing my book. But I can’t say I have found a readership beyond this beloved universe I share with my family and friends. And that is one of the things that I am most disappointed in myself with.

Perhaps I should make the poems more reader-friendly? But even if I knew how, I don’t think I would be able to. Once you start writing in your own language, there is no going back from using those sounds, words, phrases, syntax and imagery, unless it comes from within you.

MS: You published a poetry book entitled “The Pulsating Language”. Would you please explain the concept to our readers?

LLS: I came across the idea of calling the book “The Pulsating Language” or “The Language of a Pulsar” (the word “pulsar” in Portuguese has two different meanings, and I did want to make it this way) after being inspired by my good friend Daniela Euzébio from São Paulo.

She once called my poems “pulsemas” (her neologism brought together the words “pulse” and “poem”), as she believes they have a beating rhythm, akin to heartbeats. If the poems are born out of my compulsions and obsessions, it makes perfect sense to see myself as a pulsating being.

It is also a really beautiful image in astronomical terms. Pulsars are stars which have collapsed upon themselves, shrinking in size and increasing their mass to astonishing high rates, revolving around themselves at much higher speeds, and emitting these radio signals that are broadcast throughout the universe.

If one was to pick up these signals on their radio, they would believe that they come from another civilization, as they so regular and have a fixed pattern. Pulsars are believed to be our future GPS system to guide us through the universe once we finally master interstellar travel in a distant future.

I find this image to be suitable to writers and poets, even though it is terribly presumptuous and utterly inappropriate for our times. I try to cover up the blasphemy of wanting to recreate the world in my own image with ritualistic words that explain our sense of birth, of loss, of deep desire and yearning, of anger, of fear, of awe and wonder.

With every new poem and story that I write, I attempt to create my own language, a hybrid and macaronic mix of all of my experiences, cryptic and visually alluring enough, to broadcast it to the world around me, whether they listen to me or not. The pulsating language. The language of a pulsar.

MS: Rather than indicating your reader where the path is, and where the path leads to, you encourage them to find their own way. With their expressions, with their words and their interpretations, you help them find their voices…

LLS: That is the goal, yes. We all build our own universe as we read and interpret the world around us, and it is up to writers and poets to put up a mirror consisting of their words and narratives to show the readers their own reflection. Harold Bloom states that by reading, we might find fragments of ourselves, our own words, which we have long forgotten.

We usher in the familiar by grafting unto ourselves what is not familiar to us at first, until we realize it was part of us all along. All of us have been Hamlet, Robin Hood, Don Quixote, Madame Bovary, Elizabeth Bennett, and Capitu at one point in our lives. Or will be. At least in our imagination.

MS: How difficult do you find it to be a writer nowadays, in a world that sometimes fails to perceive the importance of anything that doesn’t generate vast sums of money? Can you believe in a world without philosophy, without poetry, without literature?

LLS: It is a Herculean undertaking, like Sisyphus on his daily errand. Especially because time is such a valuable commodity nowadays, and I just cannot live off my writing. As a teacher, I can do that, but it is something that takes a lot out of you, in all possible aspects.

I have resigned myself to that fact, and try to keep expectations as low as possible. As those who wrote poetry in World War I, you are supposed to keep writing, not because you can afford to, but because you HAVE TO. Onward and forward. I suppose you might encounter notoriety and financial success in your lifetime, but that will be the culmination of a combination of factors you might not entirely be on top of.

Even if, in my honest opinion, there is little room for the appreciation of poetry as it used to be, stuffed on a piece of paper, I must remain essentially optimistic in believing in the reinvention of poetry, as the media and the messaging format we use can give us conditions to do that.

A tweet could be turned into a poem. A photograph shared on your Facebook page could be turned into a super condensed poem, as a meme. Poetry is supposed to merge with film, with music, with all sorts of art or non-artistic undertakings, to survive as the supremely human form of expression.

As long as we keep our eyes open and our ears unpeeled, human arts will go on, to speak truth to power, to comfort us from the unrelenting truth of our mortality, to remind us of who we are, we were, who we can be. Otherwise, if we keep quiet, the stones will cry out.

Leonardo Lopes da Silva is Brazilian citizen currently residing in Lisbon, Portugal. As a language teacher, he lived in cities as diverse as Rio de Janeiro, London and Moscow. He has been a poet and writer since the age of 16, published his first book of poems, “A Lingua do Pulsar”, at the age of 34. You may read more about his works at facebook.com/alinguadopulsar, http://leon-keatsisms.blogspot.pt, and @TristanPulsar (Twitter).

Lisbon-born Manuel Serrano holds a Bachelor’s degree in Law from ESADE Business and Law School and a Master degree in International Relations from the Barcelona Institute for International Studies (IBEI). He currently works as Junior Editor at DemocraciaAbierta.

This article appeared originally in https://www.opendemocracy.net/