“Workers of Brazil, you exist and are valuable for us!

Women of Brazil, you exist and are valuable for us!

Black Men and Women of Brazil, you exist and are valuable for us! […]”

Silvio Almeida

Author’s note. As this article was going to print, the assault on the Three Powers Plaza in Brasília began. This is no mere repetition of January 6, 2021, however. It is yet another step in a military coup d’état in the making. Amidst the plundered symbols of democracy, we unconditionally assert that the Beauty of the Commons shall prevail against far-right Terrorism.

When pitching his last book of memoirs for a Brazilian television network in 2020, Barack Obama was asked about his statement likening Lula da Silva to a New York City mobster. The ex-president Obama had referred to at a G20 meeting in 2009 as “my man” had recently been released from a federal jail by the Supreme Court. Following the leaks compromising the ethical soundness of the anti-corruption Operation Car Wash (or Lava Jato), the Court deemed Lula had been thrown in jail before exercising his full right to an appeal. As such, due process failed to prevail. Closer to the truth was how the Operation had established a court of exception that sought to override even the powers of the Supreme Court. Moreover, Lava Jato aimed to eviscerate the Workers’ Party (PT) in a move to make Lula ineligible for the 2018 presidential elections. Technically, there was no evidence to support the allegations of corruption.

Unbeknownst to most at the time, the court had been set up by federal prosecutors who received training in the matter from the U.S. Department of Justice (D.O.J.). Behind the scenes, they were egged on by the upper echelons of the country’s judiciary and military. After 2.5 billion BRL were transferred by the D.O.J. to the court in exchange for classified information on two companies operating in the U.S., the Supreme Court moved in to overturn its sentences. Meanwhile, Bolsonaro appointed its prosecuting judge, Sergio Moro, as his minister of justice.

On television, not only did Obama prefer not to minimize the claim made in A Promised Land, he reiterated them unconditionally. “I will say that the reports of corruption that arose, have obviously played out in the Brazilian system. At that time, you know, I was not aware of all of them”, he said before veering off to speak of what “can’t be denied”, namely regarding the “gift Lula had for connecting to the people”. As the custodian of the Monroe Doctrine, the former President of the United States knew full well what the PT meant for geopolitical relations. Cynicism overcame his otherwise lucid glance as he mentioned the “real economic progress” made by Lula’s government. He could have also snickered over how Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, was under direct surveillance by the NSA during his second term, as Edward Snowden revealed in 2013.

If Obama was plausibly abreast of the lawfare techniques triggered by the D.O.J., he must have also been keenly aware of the regime change plot set into motion through means used mainly against Russia at the time. For apart from the playbook version of lawfare that landed Lula in jail for a year and a half, what strengthened the Brazilian military’s objective at gaining power was a color revolution staged mainly in São Paulo in 2016. Ties to Euromaidan in Ukraine may have eluded most at the time, despite how many of Bolsonaro’s most fanatical militants had either sought inspiration or direct training from the various ultra-nationalist groups marching through Kiev in 2014. Bolsonarist sectarians began sporting the Wolfsangel or Trident symbols standing for the white supremacist Idea of Nation. Substituting the Stepan Bandera lore, the Brazilians added t-shirt prints in homage to condemned torturers. The message began to embrace a violent anti-nationalism, subservience to the foreign hegemon and a will to destroy social programs for personal gain – a list of ingredients Bolsonaro had always stood for.

I had initially written optimistic words on how the money trail was being successfully followed now and how the public would soon discover how much of public taxpayers’ money had been spent on the color revolution that shook Brazil in 2016. Now we have confirmation it has not ended yet, though we know how many stars adorn the generals who support what is indeed a coup d’état in the making.

With Lula’s investiture into a new term of presidency now (somewhat) secured, one can (only hesitatingly) breathe beyond the airs of torment. Obama may have been the first American president to address the Arabic and North African world in Cairo, but from the Global South, whether in Africa or South America, he has fooled nobody. Lula is the Man bringing hope to the poor. For that, he has triggered the ire of the oligarchs.

Solemnity

Notwithstanding the grave events of January 8th, let us get back to the narrative. Since the end of the Cold War, there have been few cases of collective, working-class joy to be seen on the stages of liberal democracy. If sighs of relief were present in the early days of Obama’s first mandate, they were quick to disappear as the outflow of the 2007-2008 financial crisis plunged tens of millions of citizens into dire poverty.

Private property amounts to debt when it fails to capitalize. Obama’s role was to keep small-scale property from capitalizing in the hands of commoners. He allowed its transfer to the bankers responsible for the mess, and kept the latter out of jail while he was at it. While Obama’s next step for containment aimed to snuff out the movement for Black Lives, triggering its first sparks, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff jammed the thirst of private banks for astronomically raising interest rates on credit cards and overdrafts. She capped energy prices and prevented the privatization of the country’s most valuable industrial assets. By doing so, she channeled oil-derived profits directly into the various tiers of education and public health, thus benefitting above all the country’s Black and mixed-raced populations. It must be recalled that African-Brazilians are no minority in demographic terms, although, like in the U.S., they are as disenfranchised and prejudiced.

Six years after the parliamentary coup, the Afro-Brazilian majority has been resilient. A decade’s worth of fresh graduates held the crashing wave of Bolsonarism from forming an undertow. In a week of ministerial investitures, none better reflects Lula’s turn to those his programs helped enfranchise than that of Silvio Almeida, the new head of Human Rights and Citizenship. Almeida holds Ph.D.s in law and in philosophy from the University of São Paulo, and has been visiting professor at Duke and Columbia. Almeida also happens to be connected to the Sampa Hip Hop scene, made clear by his citations of Emicida and Racionais MC’s headman turned Spotify podcast star, Mano Brown. Without caring to diminish the brilliance of Marina Silva’s own address upon receiving the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change, Almeida’s speech, given on January 3, has defined him as the country’s foremost Black leader.

In his speech, Almeida minutely detailed every civil society group left defenseless in a society priding itself of its 1988 “Constitution of Citizenship”. As such, rarely have human rights converged with the right to economic equality on a federal stage. To each oppressed collectivity, he declaimed: “you exist and are valuable to us”. Head of the Luiz Gama Foundation, named after the leading 19th century Black abolitionist lawyer, Almeida came to public prominence with his 2017 essay, Structural Racism. Published by Djamila Ribeiro, he joins a now growing list of distinguished Black intellectual and artistic activists. His portfolio will be strenghtened at the Ministry of Racial Equality by Anielle Franco, sister of iconic Rio de Janeiro state representative, Marielle Franco, machine-gunned down in 2018 in as yet unsolved circumstances linked to Bolsonaro’s rise to power.

As driver to the most innovative sectors of sustainable development, Marina Silva has made a spectacular return to a most strategic ministry. Lauded for her dynamic work in Lula’s first and second governments, she fell out of favor with the PT’s more technocratic wing thereafter. Her growing public popularity and importance as protector of the Amazon forest brought her close to getting elected president. Now Lula has knighted her to oversee the Amazonia Fund, and its BRL 3 billion, a resource that has sat in stagnation for the last four years.

Through an undeniable sense of empowered, Ms. Silva presented her ministry as the cross-section of all the others. As important as the Amazon is for the climate crisis, Silva can also lead Brazil to bring peace, prestige, and power in a global south environmental alliance. A potential ally that certainly shouts out for attention is the Democratic Republic of Congo. Both countries mirror each other as clean air and fresh water suppliers, as well as strategic mineral holders. As Brazil continues to fester in world inequality indices, such an alliance could reorganize the mechanism of the wealth concentration feeding the flames on this overheated planet.

Colors and Sunlight

The January 1st investiture of Lula’s presidency had to confront the constitutional dilemma of the outgoing (p)resident’s absence in the event. As the four stars swiftly exited him on December 21 aboard the nation’s Air Force One, nobody can pretend the government he symbolized was anything less than military in structure, disposition, and will. As he signed no decree passing power to the vice-president, Bolsonaro could already have been considered a fugitive. Following the events of January 8th, he must now be charged with high treason, according to Article 308 of the Constitution.

The high command of the armed forces have snubbed the will of the people, doubling down in its opposition to social and economic changes. For decades, the generals’ enemies have lain within the state, an obsession that has left the nation’s borders frail and fissured. As absurd as it might seem from a liberal perspective, the high command’s main function has been to prevent at all costs a transformation of the country’s tax code. Today, it proved to be an enemy from within. Power recognizes no vacuum. Income and corporate tax has been weaponized to perpetuate its concentration of oligarchic wealth.

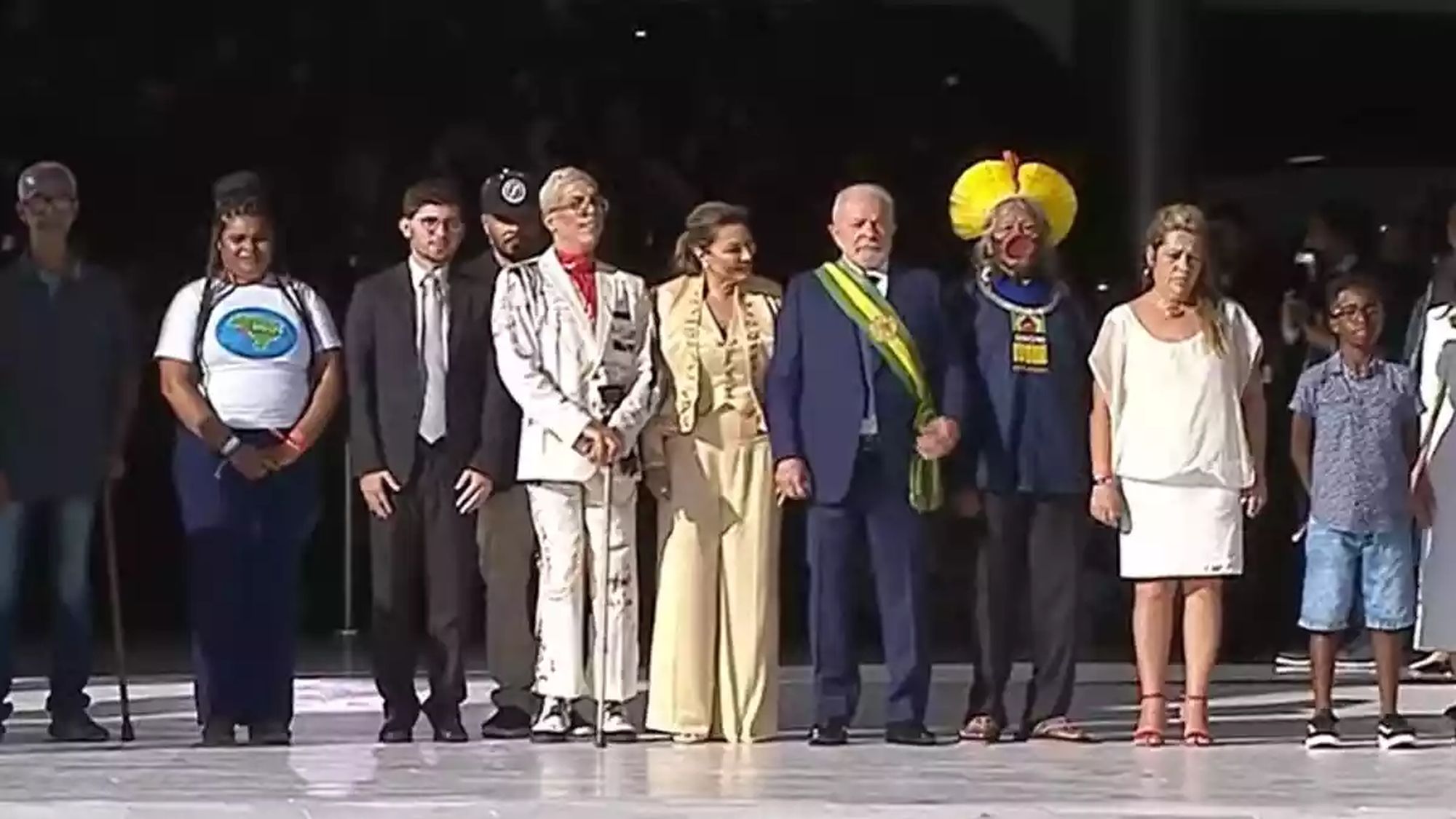

To disapprove smoothly and lovingly of such constitutional insubordination, Lula, and his wife, Rosangela’s, idea for the passing of the presidential sash brought beauty to Jean- Jacques Rousseau’s political concept of the general will. Six persons from civil society transferred the presidential sash amongst each other, the first being the Elder of Brazil’s first peoples, Chief Cacique Raoni Metuktire of the Kayapo. The Black garbage recycler, Aline Sousa, was the woman to finally lay the sash on Lula’s shoulders, proclaiming him President.

Happiness in the future perfect

Earlier in December, Lula revealed how his choice for Minister of Culture would go a step further than what Gilberto Gil did masterfully as of 2003. One recalls how Gil made the U.N. General Assembly dance to his sun soaked beats in 2009, with then Secretary-General Kofi Annan keeping the beat on the atabaque. Now, it is singer and actor Margareth Menezes’ turn. Like Gil, she hails from Bahia State, thus representing Afro-Brazilian music even more at the roots level than did her predecessor’s tropicalist vibe. Her nomination to a ministry Bolsonaro had extinguished outright made the energy and joy overflow during the week of ministerial investitures.

One wonders whether political radicalism has ever appeared as colorful as in a LGBTQIA+ flag. Also part of the festivities saw a Ministry for Indigenous Affairs finally headed not only by a leader of a first and traditional nation, but by a woman. As witness to the genocidal reality facing the first nations, Sonia Guajajara will propel indigenous cultures to the center of the political arena, as she intends to make demarcation of lands a shift in the country’s legal tradition. After Bolsonaro had turned the riot police against First Nations women on the Esplanade of the Ministries during a peaceful protest in 2021 against Covid-19 exposure and genocide, a time of national redefinition seems to have arrived.

Fernando Haddad, another University of São Paulo Ph.D. in philosophy, with a Master’s degree in economics, takes over a ministry that under Bolsonaro had privatized everything but itself. Surely, São Paulo residents are disproportionately represented in the new federal government. Yet considering how state electors chose one of Bolsonaro’s lieutenants as governor, Tarcisio de Freitas, Lula’s cabinet cannot be judged on its São Paulo portfolio alone. Such suspicions were confirmed today as a muzzling order came from Freitas’ cabinet about the attack on the federal buildings of the Three Powers. São Paulo is thus set to be the next stage for the Bolsonaro project. The governor’s slippery remarks about his Don do little to change the plan to continue the same wave of destruction undertaken thus far: super-salaries for the executive and senior members of the state apparatus; hyper-privatization; tax protection for the wealthy through minimal tributes on corporate profits, dividends, and inheritance. These measures only embolden the traditional landed and financial oligarchy, which sees no difference between entitlement and crime.

By contrast, Haddad is the man of the hour. PT candidate in the 2018 presidential elections and former Minister of Education, he has a truly impressive record as both a social theorist and public administrator. But unlike another famous USP intellectual, the once “radical sociologist” Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Haddad has never renounced the authors on whom his scholarship is based: Karl Marx and Jürgen Habermas. These German thinkers have framed his dual commitment to social justice, deep economic analysis and discourse ethics.

To propel the country out from its noxious inequality, he has no choice but to halt the extremist programs of privatization and deindustrialization of enterprises, and revert the submission of the country’s workers to conditions of pauperism. What is the problem with privatization, and what is the link between the three focal points listed above? For one, privatization places national assets into the hands of the wealthy. Granted they might be Brazilians, although they tend not to reside in the country. Second, privatizations when undertaken as state policy rarely tend to be properly taxed—if taxed at all. Such policies do not require the companies buying state assets, often strategically important ones, to have their headquarters in the country, let alone declare revenue and assets here. Privatization when conducted to please foreign interests is also a ploy to either cash in on cheap labor or eventually destroy a nation’s industrial base completely.

Until mid-2022, the Bolsonaro government managed to draw in some BRL 300 billion from such measures. Where did this money go? Into society, it surely did not. Figures for poverty and extreme poverty have skyrocketed, roughly affecting some 30 and 18 percent of the population, respectively. Meanwhile, as Haddad emphasized in his inaugural speech, Bolsonaro has used up to 3 percent of the 2022 GDP, namely BRL 300 billion, for his failed bid at re-election. Currently, Brazil’s prime interest rate hovers at 13.75 percent, the highest in the troposphere. This also amounts to legalized theft of a population whose average salary buys nothing but debt.

Haddad is a suave intellectual who has worked the chords and boards of the media battlefield. Answering only to the dominant sectors, these are the outlets that brought Bolsonaro to power by orchestrating the destruction of the PT. Haddad had to face them bravely at a time when corporate media fomented a dangerous hatred of his Party. Freshly armed green-yellow hoards, with reflexes conditioned by psy-op techniques in psychological confusion or shock therapy, were trained to attack anything red. Since then, the media instills the angered with the leviathan figure of the “market” in another attempt to coerce the PT into retreat. Even journalists with integrity are vetted through vengeance.

Haddad also arrives with a vision of a common South American currency. Brazil’s Real (BRL) trades internationally only through indexation to the US dollar. One would expect the obstacle to a common currency to arise from how independent it seeks to become regarding the latter. Yet, structural obstacles are anything but absent in this scenario. Although one would hesitate to characterize this idea as a test, should he be successful it could partly prove Marx’s conjecture about capital periodically adjusting itself wrong.

For his third term, Lula has not merely encountered a more sophisticated and politicized country than the one he left in 2010. It is the country his political vision and resilience helped create that has come out to greet him. At the end of this week of beauty, this majority has also had to witness white supremacist terrorists destroy the symbols of the country. No other wish stands quite as appropriately as the one Minister Haddad uttered last week: “Thank you, President Lula. Brazil shall be happy again!”

One can only aspire for this happiness to increase with newfound independence, rid of further malfeasance by the unipolar hegemon. The terrorists did much more than ransack the buildings of the Three Powers with their innumerable symbols. They defiled their own dignity.

Norman Madarasz is currently invited Capes/Print fellow in political and economic philosophy at Université Paris 8.