President Lula da Silva, together with his team, are to be congratulated for having organized this G20 Summit in Rio so well, which was described as “excellent,” with special praise for the Global Alliance against Hunger and Poverty, and even some progress in areas where expectations were lower, such as the reform of global governance.

The same can be said about the discussions on climate change, although Brazilian expectations were higher than the results achieved, but “steps that will make a difference” were still taken, according to Marcos Caramuru, international advisor to the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI) and former Brazilian ambassador to China.

Of course, there was also a lot of discussion about the repercussions of Donald Trump’s return to the US presidency, which points to the creation of new alliances, thus requiring the strengthening of Brazil’s relationship with its BRICS partners, and particularly with China, currently Brazil’s largest economic partner, with bilateral trade exceeding US$ 160 billion last year, and with which the Lula government seems to have a great ideological affinity.

On the one hand, Brazil is one of the few countries with a positive trade balance with China. In addition, both countries have major joint projects that aim to strengthen these ties even further, such as the roads that are being built to give Brazil access to the Pacific Ocean, thus making it a bi-oceanic country, like the United States is. This has always been one of the biggest advantages the US has had over Brazil, which has always depended on the Panama Canal to export to Asia.

However, as we know, the cost can be very high, since this cost is assessed according to the value of the cargo, or 0.5% of that value, which can cost more than a million dollars for just one passage through the canal. This, of course, makes the Brazilian product more expensive, and not to mention the time it takes to reach and cross the canal.

On the other hand, China’s need to import Brazil’s soybeans and other commodities, as well as iron ore, “in exchange,” so to speak, for Brazil’s purchase of Chinese high-tech products, could create a certain mutual dependence that could keep Brazil forever as a commodity exporter and high-tech importer.

This huge investment that China is making in these Pacific outlet projects will certainly come at a very high price for Brazil, perhaps even too high for Brazil’s ambitions of becoming a superpower like the United States and China themselves have become. This marriage of convenience between Brazil and China could prove to be a double-edged sword, because a country without autonomous high-tech development will never become a superpower. Nothing could be clearer than that.

I don’t think I’d be exaggerating to say that, given the instability that Vladimir Putin has created for Russia by invading Ukraine, and the conflicting relations that have always existed between India and China over territorial disputes, Brazil, due to the fate and ideology of the current government, will end up becoming China’s biggest economic and political partner within the BRICS.

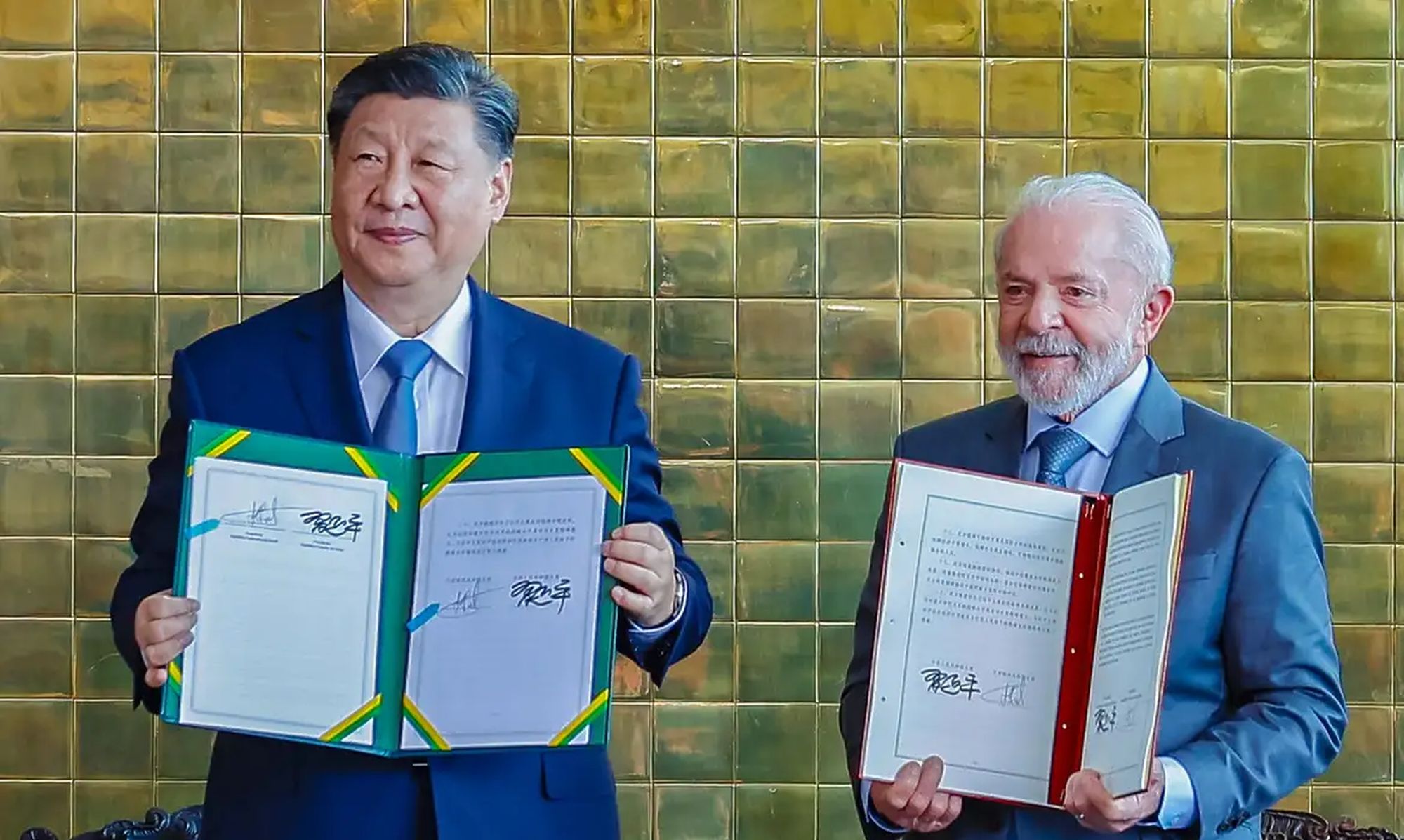

After the end of the G20 summit in Rio, President Lula received the Chinese President in Brasilia, where both heads of state signed dozens of trade and development agreements, while the two held talks in Brasilia with the aim of deepening bilateral ties.

And while on the one hand this marriage between Lula da Silva and Xi Jinping could bear good fruit, given the ideology of both governments, it could have serious consequences for Brazil, which would end up becoming a client state of China, whose GDP is more than 18 trillion dollars compared to Brazil’s GDP of around 2 trillion dollars.

And as in any marriage of convenience, he who has more economic power, speaks the loudest, and that worries me a lot.

Glauco Ortolano is an Associate Professor at the Defense Critical Language and Culture Program of the Mansfield Center, University of Montana. He has taught at the Lauder Institute of the University of Pennsylvania, and more recently courses in Geopolitics to officers of the US Armed Forces. He was also appointed Peace Ambassador by Le Cercle Universel des Ambassadeurs de la Paix.

The views in this post do not represent those of this publication, nor do they represent those of the author’s employer.