On the second day of COP26 – the UN climate negotiations in Glasgow – the world celebrated an announcement made by leaders from 124 countries. In the Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, world leaders boldly pledged “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 while delivering sustainable development”.

But amid praise for this declaration, there is also serious doubt whether major signatories can deliver on its ambitious promises. In particular, all eyes are on Brazil.

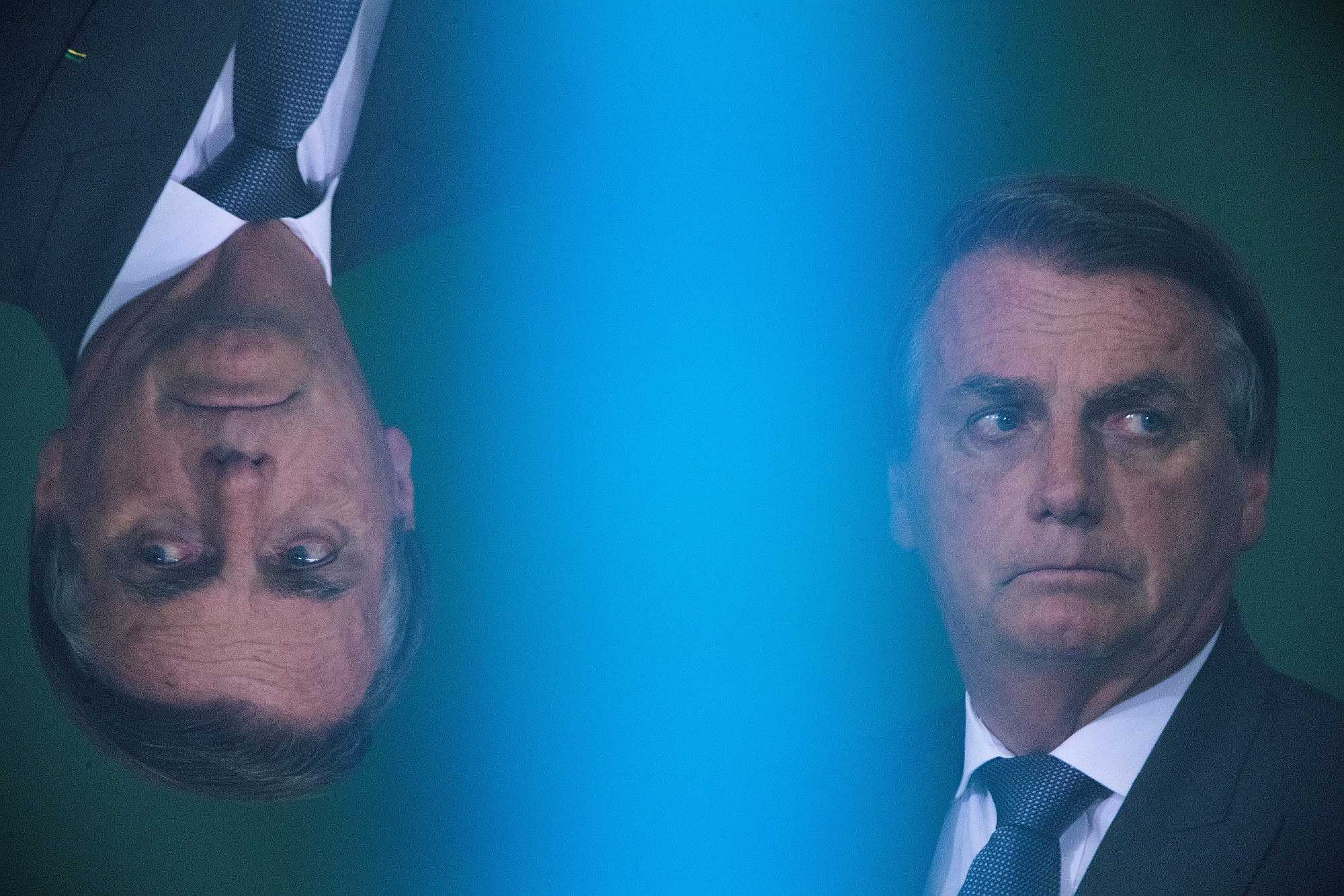

Not only does Brazil contains large portions of the Amazon rainforest and the Cerrado ecosystem (the largest area of savannah in South America), but government policy on environmental issues has become particularly destructive under the presidency of the country’s current leader, Jair Bolsonaro – who was notably absent from COP26.

Seeing how Brazil’s government – and Bolsonaro in particular – has reversed progress on deforestation in the past leaves us less than optimistic about its sincerity this time.

Deforestation in Brazil

Brazil has previously seen different sectors of its economy set their names to ambitious deforestation goals. In July 2006, the six biggest multinational commodities traders signed the Soy Moratorium, pledging to stop buying soy from traders implicated in illegal Amazon deforestation. Three years later, Brazilian slaughterhouses signed the Zero Deforestation Commitment, making similar promises.

Consequently, between 2009 to 2014, Brazil experienced its lowest ever Amazon deforestation rates. This small period of limited progress was only possible due to collaboration between companies in Brazil, the Brazilian government, and several major players within the global commodity supply chain.

Our research showed that this short-lived progress was in part the result of a campaign by Greenpeace Brazil, as well as the actions of the Brazil Federal Prosecutor’s office. A combination of “name and shame” campaigns, police involvement and legal agreements with the federal prosecutor’s office increased pressure on slaughterhouses, threatening the sector’s profits, and resulting in the partial engagement of companies to tackle deforestation.

Unfortunately, the political alignment between these sectors has eroded since the political and economic crises that hit Brazil in 2014. Since Bolsonaro took office in 2019, deforestation rates have started to increase at a fast pace again, reaching a 12-year high. Fighting deforestation through multilateral declarations like this one has therefore fallen short before.

In 2014, the New York Declaration on Forests attempted to establish a similar objective: ending deforestation by 2030 after halving it by 2020. As many as 40 countries signed it, but Brazil was not one of them.

Even though the New York Declaration was also celebrated, its actual impact was limited. In 2019, a five-year follow-up report concluded that “there is little evidence that these goals are on track”, stating that less than 20% of overall forest restoration goals were met.

It’s important to note that the mix of signatories to this new COP26 declaration is unprecedented. Countries with significant forest coverage, such as Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, have signed – some for the first time.

The list of signatories also includes countries like the UK, Japan and Germany – some of the biggest consumers of commodities like palm oil, cattle, soy, cocoa, timber and rubber – the production of which is intrinsically linked to deforestation.

The financial sector is also sending signals in favor of reducing deforestation. More than 30 leading financial institutions, which together control over US$ 8.6 trillion in assets, have committed to eliminating commodity-driven agricultural deforestation from their investment portfolio by 2025. Yet, similar to the pledges made by nation states, only time will tell whether these promises manifest in substantive action.

Bolsonaro’s Track Record

Elsewhere in the climate negotiations, Brazil’s new Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – non-binding national climate plans – include cutting 50% of its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. This increase, from the 43% cut previously pledged in 2015, sounds progressive.

But it is actually nothing more than creative accounting. Bolsonaro’s government is trying to change the historical baseline on this commitment. This change would mean that, in the best case scenario, Brazil keeps its original NDC. In the worst case scenario, it would actually allow for more emissions. This makes it harder to trust Bolsonaro’s environmental promises elsewhere.

Bolsonaro is well known for his disregard for environmental governance. He has tried to increase access to the Amazon for the commodities sector, claiming that relaxing environmental regulation is key to achieving economic growth. He also has a track record of attempting to dismantle environmental agencies and limit their budgets.

Maybe this new declaration will give world leaders an upper hand, by allowing them to impose economic sanctions on Bolsonaro’s government if he breaks the agreement. Nevertheless, as negotiations at COP26 continue, it is vital that Bolsonaro and his anti-environmental, anti-globalist ideology does not undermine the talks.

Marcus Gomes is a lecturer in Organisation Studies and Sustainability at Cardiff University

George Ferns is a lecturer in Organization Studies and Sustainability at Cardiff University

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original article here: https://theconversation.com/brazil-signs-agreement-to-halt-deforestation-but-bolsonaro-cannot-be-trusted-171091