As Brazil faces one of the worst Covid-19 outbreaks in the world, a smartphone app is helping residents of impoverished areas known as favelas survive the virus threat amid sudden mass unemployment.

So far, the Latin American country has recorded over 120.000 deaths caused by Covid-19. The shutdown of economic activity wiped out 7.8 million jobs, mostly affecting low-skilled informal workers who form the bulk of the population in the favelas.

Emergency income distributed by the government is limited to 60% of the minimum wage, so families are struggling to make ends meet.

Many blame president Jair Bolsonaro for the tragedy. Bolsonaro, a far-right populist, has consistently rallied against science-based policies in the management of the pandemic and pushed for an end to stay-at-home orders. A precocious reopening of the economy is likely to increase infection rates and cause more deaths.

In an attempt to stop the looming humanitarian catastrophe, a coalition of activists in the favelas and corporate partners developed an app that is facilitating the distribution of food and emergency income to thousands of women spearheading families. The app has a facial recognition feature that helps volunteers identify and register recipients of aid and prevents fraud.

So far, the Favela Mothers project has distributed the equivalent to US$ 26 million in food parcels and cash allowances to more than 1.1 million families in 5,000 neighborhoods across the country.

“Women are the cornerstone of life in the favelas”, says Claudia Raphael de Oliveira, president of the Unified Center of Favelas (CUFA), the group leading the Favela Mothers initiative. “Many women have to feed not only themselves, but also their children and other relatives, so when their income falls short their entire family is affected.”

Oliveira says that companies and civil society organizations were quick in reaching out to offer donations. She explains that aid serves a double purpose: it provides temporary relief for the families and helps flatten the curve by ensuring people have the means to stay at home during the pandemic.

“Aid arrived right on time. My daughters are hungry and sometimes I have nothing to feed them”, says Luma, a resident at the Parque Esperança favela in Rio de Janeiro, in a video posted on CUFA’s social media. She is a mother of five and her husband is unemployed. “I am glad people are finally looking to the favelas. I’ve lived here for three years, and this is the first time I see such a beautiful initiative.”

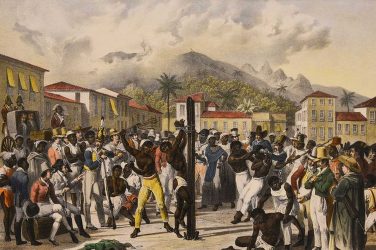

Respecting social distancing guidelines is a major challenge in the favelas. These impoverished neighborhoods expanded rapidly on the outskirts of big cities in the 20th century. They house working-class families that were forcibly expelled from central areas and people that migrated to the big city from other parts of the country. They are also home to many descendants of enslaved Africans, reflecting a legacy of racial segregation that persists in Brazil to this day.

After decades of neglect by authorities, millions of favela residents live in crowded spaces, often in hastily-built shacks with little or no access to running water, sanitation and public health services. These citizens are disproportionately vulnerable to outbreaks of diseases like Covid-19.

“This pandemic is revealing what has been the reality in the favelas for many years”, says Marcivan Barreto, the head of CUFA in the state of São Paulo. Since the pandemic began, he has been working seven days a week to coordinate Favela Mothers donations in the region. “Favelas face many issues, but they are full of people who want to do good. There is an enormous sense of solidarity and unity.”

Barreto is a resident of Heliópolis, the biggest favela in São Paulo, with more than 200.000 residents. It is one of the worst-hit areas in the city, with more than 100 deaths caused by Covid-19 despite residents’ best efforts to contain the spread of the virus. “Unfortunately, some folks only realize the severity of this crisis after they lose loved ones”, he complains.

The distribution of aid is often obstructed by the police. Barreto says that law enforcement agents regularly stop, and sometimes confiscate, CUFA’s vehicles. In May, volunteers in the Cidade de Deus favela in Rio de Janeiro had to halt the delivery of food parcels due to a shootout during a police operation that left one teenager dead.

“Repression got worse during the pandemic as officers are using violence to impose lockdown measures, but security forces have been interrupting people’s lives in the favelas for a long time”, says Barreto.

According to Danielle Klintowitz, an urbanist architect and coordinator at the Instituto Pólis research group, “old age and health conditions are not the only factors putting people at risk of dying of Covid-19; social and economic factors also play a role”. She says the virus is disproportionately hitting Blacks and residents of favelas, reflecting chronic inequalities in the country.

The first Covid-19 cases in Brazil were recorded in late February among members of the white elite returning from holiday trips in Europe and the US. When local authorities imposed stay-at-home orders in mid-March, coronavirus outbreaks were still largely absent from poor areas, but unbalanced lockdown measures gradually changed that scenario.

As Klintowitz explains, “upper and middle-class Brazilians can only afford to stay at home in the pandemic because lower-class workers are routinely exposed to the coronavirus in essential services”. These include activities like food delivery, trash collection and healthcare.

This way, essential workers are getting infected and bringing the virus back to their communities – and favelas are now experiencing some of the worst Covid-19 outbreaks in the country.

Community mobilization initiatives like the Favela Mothers can make a big difference. Paraisópolis, a favela with more than 100.000 residents in São Paulo, implemented a comprehensive strategy to control the virus that has proven to be a success.

Besides distributing aid, trained volunteers are tracking infected residents from door to door in Paraisópolis – those unable to practice social distancing at home are being transferred to makeshift isolation centers set up in inoperative schools. They have also hired healthcare personnel and rented ambulances to compensate for the absence of public services in the region.

As a result, coronavirus infections in Paraisópolis are nearly three times lower than the recorded average for the city of São Paulo, according to a recent study by Instituto Pólis.

“Paraisópolis has achieved outstanding results in the fight against Covid-19 thanks to enduring community mobilization and long-standing solidarity networks”, says Klintowitz. “Unfortunately, this is not the reality in most favelas, but all across the country we see residents taking action to save lives in the pandemic.”

As Brazil’s economic situation continue to worsen due to the health crisis, activists in the favelas are seeing contributions from individuals and corporations wither. Barreto, from CUFA-São Paulo, says he hopes the government and civil society will pay more attention to their demands.

“We need support to continue delivering aid through the pandemic and after the virus threat is gone”, he says. “The suffering of people in the favelas will remain; many will have to start their lives from scratch.”

Gabriela Onofre, Chief Marketing Officer at the technology startup Acesso Digital, says businesses have a lot to gain from helping those in need – her company is providing the facial recognition software used in the Favela Mothers app.

“Knowing that our service is helping to improve thousands of lives in such critical times boosted our team’s morale and gave us new ideas for innovation”, she says. “We hope this solidarity drive is here to stay.”

This article appeared originally in Open Democracy https://www.opendemocracy.net/