Leaning on the balcony railing at her rickety house, perched above the stairs and alleys of a poor community in Salvador, capital of Brazil’s Bahia state, Vanessa Braz da Conceição looks up at the night sky. For this 35-year-old pharmacy student, it’s her way of connecting with nature amid the city’s concrete jungle.

“I spend hours here, enjoying my relationship with them,” she says of the sun, the moon and the stars.

Vanessa is a member of the Pataxó Indigenous people from the Coroa Vermelha region in the far south of the state, and stargazing keeps her connected to her origins.

From the window of the simple home where she lives alone, the mass of concrete houses couldn’t represent a more striking contrast to her native village, which is close to the city of Porto Seguro, a 10-hour drive south along the Atlantic coast from Salvador.

Porto Seguro is also where the first European colonizers set foot in what is today Brazil, back in 1500; Salvador is where they established their first capital city.

“Every Indigenous person has a strong connection with nature,” Vanessa says. She adds there’s also beauty in the urban scene, like the buildings in the background of the massive valley of common houses that make up the community where she lives, in the heart of Salvador’s Federação district.

It’s a place with a rugged geography, full of slopes and steps, like much of the metropolis. “I prefer nature, but the city is also beautiful.” In her daily life, Vanessa works with chemical substances at the pharmaceutical school at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). She says she has always appreciated the alchemy of herbs to cure bodily ailments. “Even the teachers ask me about leaves.”

The last census conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), in 2010, showed 7,552 Indigenous people living in Salvador, out of a total population at the time of nearly 2.7 million.

Some of these Indigenous people, like Vanessa, are still strongly linked to the villages where they have their roots. Others, probably self-declaring as Indigenous, have lost ties with their peoples.

In either case, many of them live in Federação district. They’re drawn there both for the proximity to the university and the presence of others like them. “We help each other,” Vanessa says.

The same census showed that 579 indigenous individuals lived in the subdistrict of Vitória, which is part of Federação, now informally considered “Indigenous territory.” At the time of the census, Vitória was home to the sixth-largest number of Indigenous residents in Salvador, all from various ethnic groups.

At the top of the list were the subdistricts of São Caetano (1,208 Indigenous people), Pirajá (1,131) and Amaralina (827). In all of them, however, Indigenous residents accounted for less than 1% of the total population.

There are no figures showing an increase in the number of Indigenous individuals living near the university, but it’s clear that the campus attracts students linked to the quota system. Currently, 205 of the roughly 28,000 students enrolled at UFBA are Indigenous, according to university data.

“The quota system fulfilled its goal of democratizing access and it didn’t prevent Indigenous students from performing well,” says Penildon Pena, UFBA’s undergraduate dean.

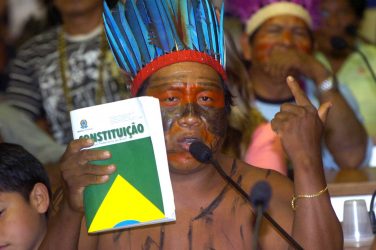

For Salvador’s Indigenous residents, academic achievement is only one of many battles to wage. The first of these battles is to be able to preserve cultural principles. But perhaps the most difficult one is facing the prejudice of others unfamiliar with the sight of Indigenous people wearing jeans and using smartphones, with features different from those depicted in historical texts like José de Alencar’s The Guarani, published in the late 19th century.

“We always face questions like, ‘Why is your skin light? Why isn’t your hair totally straight?'” Vanessa says.

Eight in ten Salvadorans are Afro-Brazilian, according to the 2010 census; the city was a major port for the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Native Brazilians living here and looking for ways to demarcate territory within the city have taken to wearing their traditional dress and painting their bodies.

When Vanessa goes somewhere with her body painted, people love it, she says. “Some think it’s a tattoo.” For her, the most difficult connection is with the Patxohã language of her ethnic group, of which she only knows only a handful of words. “Maion is the sun, right? Terré means rain; werymerrye is love; a flower is a tiarra’, and coffee is torron.”

Her closest cultural ties are to plants. Even though she’s on track to becoming a pharmacist, Vanessa prioritizes the use of medicinal teas. She scours the woods on the university campus for ingredients.

To treat urinary tract infections, she recommends a cup of broadleaf plantain tea, a very popular medicinal plant, or green corn if it’s corn season. In the case of piriri (bellyache), she prescribes guava sprouts.

Maria Hilda Paraíso is one of the top experts on the history of Brazilian native peoples, and is a social scientist and anthropologist at UFBA. Since 1971, her research has focused on the trouble that Indigenous people have had in adapting to the urban environment. She says one of the ways they make their experience less complicated is to live with other Indigenous people.

“It’s hard to change habits and hierarchical social relations,” Paraíso says. “When they live with other Indigenous people, it becomes, say, less painful.”

LGBT Phobia ‘Imposed by White People’

Yacunã Tuxá, 27, is a literature and visual arts student at UFBA, where she’s enrolled under her Portuguese name: Sandy Eduarda. She comes from the Tuxá ethnic group, originally from the municipality of Rodelas in northern Bahia. It was her community who encouraged her to pursue higher education, she says.

“I had to leave the village so I could learn non-Indigenous people’s knowledge to be able to help my people in the struggle for territory,” she says.

Maintaining a presence in cities and universities is a way for Indigenous people to keep their culture alive, Paraíso says. In many cases, they not only learn relevant information about their peoples but also become agents who convey ancestral knowledge. They all expect the university to be more welcoming than other spaces. But in practice, that’s not always the case.

Within UFBA and also outside it, Yacunã Tuxá says she experiences the same struggle that her people have faced for more than 30 years, ever since they were evicted from their original village to make way for a dam.

When the old town of Rodelas was flooded, the Tuxá villagers moved to an area that was no longer demarcated as Indigenous territory. Today, in Salvador, Yacunã Tuxá says she feels like a fish out of water — like a matrinxã fish (Brycon amazonicus) taken from the São Francisco River that runs through her hometown.

In Alto das Pombas, a community in the same Federação neighborhood, Yacunã Tuxá has two loves. One is her girlfriend, Itayná Ranny; the other is the struggle for acceptance of the Indigenous presence in Salvador.

“It’s a very stereotyped view,” she says. “They say, ‘How can you be an Indigenous person? You go to the university, you wear jeans, you wear sneakers.'”

As a lesbian and an LGBTQIA+ activist, Yacunã Tuxá has also had to struggle to gain space in the village itself. “I stood my ground and said, ‘Yes, that’s right!’ I haven’t given up my culture to experience my sexuality, you know?”

A member of the Tibira Collective, the first Indigenous LGBTQIA+ group in Brazil, she says LGBT phobia is not part of Indigenous tradition. “That discourse doesn’t belong to us or to our culture. It has been imposed by white people.”

Yacunã Tuxá has lived in Salvador since 2015, and her artwork makes clear that this place, as much as any other in Brazil, is her home. “Yacunã,” after all, means “daughter of the land” in her native Dzubukuá language. “This area where we are standing right now used to be Indigenous territory,” she says: The city was also the place of her ancestors.

Urbanized by Force

It’s not just in the center of Salvador but a good part of its outskirts and the so-called Ferroviário district where Indigenous people have settled since early colonial times. When the Portuguese arrived here 500 years ago, they made Salvador the capital of Brazil. Now, the entry of Indigenous people into the urban environment is controversial. In fact, they have always been urbanized, and by force.

Fabricio Lyrio Santos, an expert on the history of native peoples at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia (UFRB), says the first idea that needs to be deconstructed is that the colonists founded the city on empty territory.

“This was not a desert island. It was a territory inhabited by a number of diverse peoples,” he says.

The region was home to different Tupinambá groups — complex peoples with their own social dynamics. The local geography, with its abundance of water and position by the sea, favored fishing and agriculture. Their first contact with the Europeans was friendly; there was no conflict. Indeed, the first Portuguese borough in Brazil — Vila do Pereira, now the tourist beach of Porto da Barra in Salvador — was built with the “friendship” of native peoples in 1536.

It was only later, when the Indigenous people understood that they were being exploited, that disagreements and rebellions began. The Portuguese established a general government in 1545 and began planning the construction of the first colonial town. Many Indigenous peoples did not join the rebellion. Instead, they were roped into building Salvador, founded in 1549, in an arrangement that was a de facto form of slavery.

“The Indigenous man was the Negro of the land,” Lyrio says. In the process, many fled and many others were killed or died from diseases introduced by the colonizers.

At the time the Portuguese arrived, there were five or six villages in the area that’s now the center of Salvador. They stood in what are today the neighborhoods of Campo Grande, after which Bahia’s traditional Carnaval circuit is named, and in the historic city center itself, where the Pelourinho district is located.

Across the current metropolitan area of Salvador, there were an estimated nearly 30 Indigenous villages and settlements. Many of these places, which include poor communities, still maintain their Tupi or Tupi-Guarani Indigenous names: Itapuã (“stone that snores”), Abaeté (“wise, truthful man”), Pirajá (“fishpond”), Periperi (“region of many plants”).

“There is a distinction between villages (aldeias) and settlements (aldeamentos). The latter were run by white Jesuits,” Paraíso says.

A text attributed to José de Anchieta, an early Jesuit missionary, mentions 16,000 Indigenous people in settlements run by the Jesuits in Salvador in 1561. It also says there were 40,000 natives in 14 villages between 1560 and 1580.

The process of urbanization of Salvador’s native peoples reached its peak in 1756, when the Marquis of Pombal razed the old settlements and turned them into boroughs. By the late 19th century, the natives had lost their rights.

United Against Prejudice

After centuries of exploitation, violence, disease and enslavement, Indigenous people are still fighting for territory where a city of 3 million people now stands. Many of them move to Salvador in search of specialized education, and few are as determined in this mission as 30-year-old Rutian do Rosário Santos, who, like Vanessa Braz da Conceição, is from the Pataxó ethnic group.

A member of UFBA’s second batch of Indigenous quota students, she has lived in Salvador since 2008. She has a degree in economics and is now studying law at the same university.

Also like Vanessa, Rutian Pataxó comes from Coroa Vermelha, and says Indigenous people need to study and improve.

“Despite being in a black city, the university still belongs to straight white males. When I arrived, there was an invisible barrier between quota students and non-quota students,” she says.

She adds the definition of Indigenous people living in urban areas is controversial even within their own movement. “Is it only those who live in cities and have no connection with their villages who count? Or those who maintain ties to their origins and moved to the city? Or simply those who live in the so-called urban villages close to big cities?”

The fight to preserve their culture unites all of them, and they are helped by the fact that Salvador is a predominantly Afro-Brazilian city. Rutian Pataxó and other Indigenous people tap into this font of blackness to preserve their own ways.

In the Cidade Baixa area that overlooks the Bay of All Saints, they shop at the São Joaquim Street Market, which sells utensils and ingredients used in religions of African origin. They use banana leaf in place of the patioba palm leaf that they can’t find here; they also buy clay utensils to prepare their traditional food, she says.

While the relationship between the Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous people is marked by tensions shaped by centuries of colonization and enslavement, there has always been a dynamic exchange. Over time, these two exploited cultures have merged, sometimes even religiously.

“This can be seen in a striking way in the environment of caboclo candomblés,” says UFRB historian Lyrio, referring to Indigenous-white mixed-race individuals (caboclo) who practice the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé.

In their search for space, Indigenous people have tried to remain cohesive. That’s why everything is done in groups, Rutian Pataxó says.

“What most strikes me in the city is selfishness, individuality. The collective spirit is something that we learn at home. We are always together,” she says.

Despite this, she says she doesn’t know if she will ever return to Coroa Vermelha. “I think you should contribute to the struggle wherever you are.”

For Rutian Pataxó, love for the Indigenous cause has no territorial boundaries. It travels beyond the horizon.

Data research and analysis: Yuli Santana, Rafael Dupim and Ambiental Media.

Translated by Roberto Cataldo

This article appeared originally in Mongabay. Read the original article here: https://news.mongabay.com/2021/05/indigenous-in-salvador-a-struggle-for-identity-in-brazil-first-capital/